“I have always done what they wanted me to do, teach reading, writing and arithmetic. Nothing else – nothing about dignity, nothing about identity, nothing about loving or caring. They never thought we were capable of learning those things.”

Back in the days of Creole Louisiana, French engineers redirected a loop of the Mississippi north of Baton Rouge. The resultant oxbow - the ‘False River’ - is today a peaceful community of waterside houses with decks and jetties and motorboats, interspersed with imposing plantation estates.

One contemporary home with a large “G” on the gate is owned by a man who remembers life on False River in very different circumstances.

Ernest J. Gaines was born in 1933 to a family of sharecroppers. One of 12 siblings, he was raised by an aunt who was crippled and had to drag herself across the floor of their home, a rough shack where the family had lived since the days of slavery. He worked in the fields as a child, gathering onions and white potatoes. He attended a few years of grade school, held in a church built by the sharecropper families, sitting in the pews with the other kids, balancing schoolwork on their knees. But he showed promise, and he was encouraged to escape this life of rural black poverty. In 1948, aged 15, he caught a bus to New Orleans and, from there, moved to San Francisco.

He returned to Louisiana in the early 1980s to take up a tenured position as a professor of Literature at the University of Lafayette.

Twenty years later - by then a celebrated author, feted by Oprah - he bought land on the very plantation where his family once worked. He and his wife Dianne restored the church where he'd studied as a child, and they moved it onto their property. And yesterday, to our great privilege, we sat at their dining room table and asked Dr. Gaines about his life.

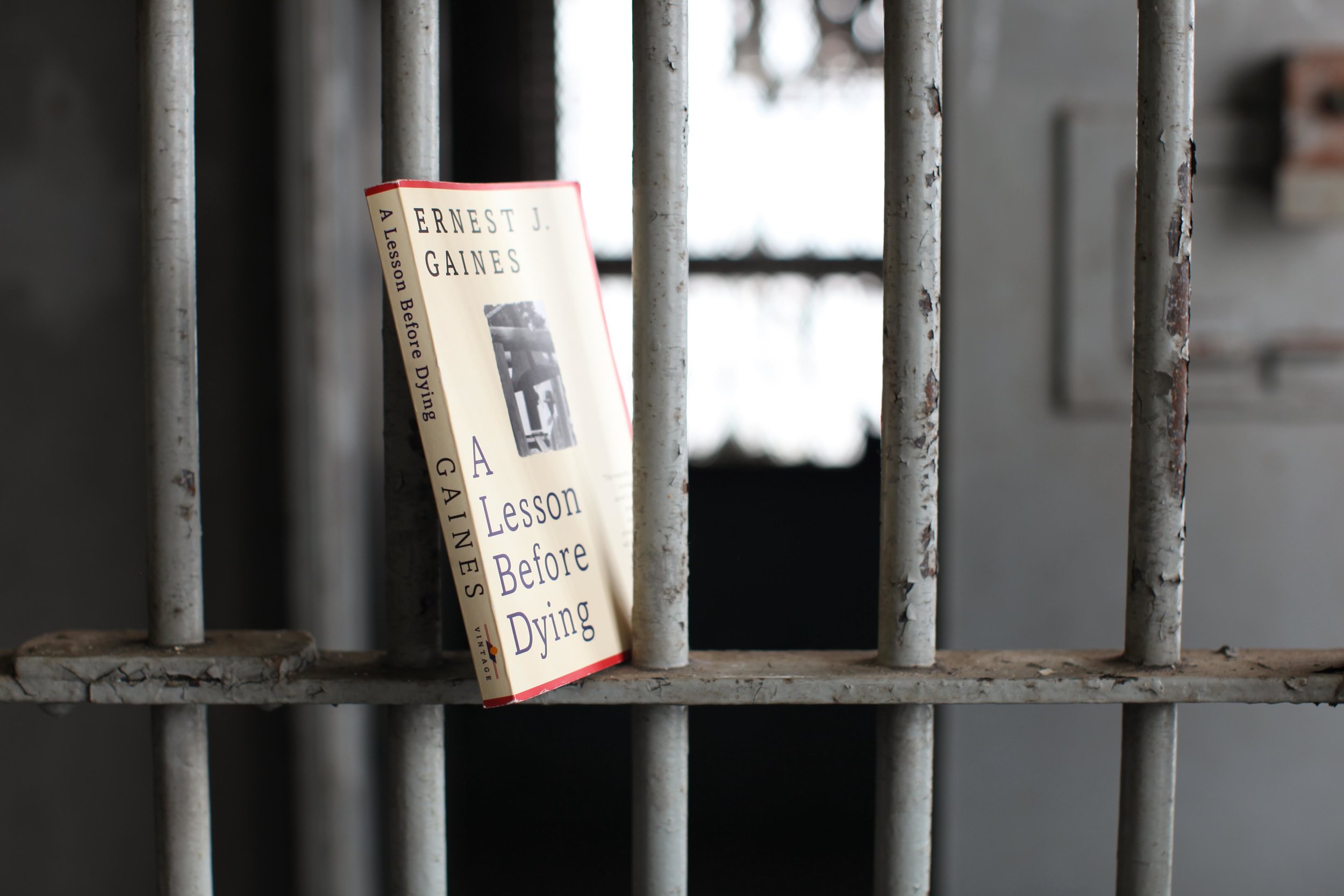

We’ve been reading his 1993 novel ‘A Lesson Before Dying’, a classic of modern African-American fiction. It’s set in the late ‘40s in Pointe Coupée Parish (‘St Raphael' in the novel), with much of the action focused on the town of New Roads (‘Bayonne’), which is just north of the Gaines’ home around the curve of the False River.

The novel describes the relationship between Grant Wiggins, a schoolteacher, and a young man, Jefferson, a prisoner awaiting execution in the parish jail.

Jefferson has been involved in a botched raid on a liquor store in which a white storekeeper has died. As the only survivor of the raid, Jefferson stands trial for murder, and hears his defense attorney argue against the death penalty on the twisted logic that Jefferson is somehow less than a man:

“Gentlemen of the jury, look at him - … What you see here is a thing that acts on command. A thing to hold the handle of a plow, a thing to load your bales of cotton, a thing to dig your ditches… What justice would there be to take this life? Justice, gentlemen? Why, I would just as soon put a hog in the electric chair as this.”

Jefferson is silent and sullen as he awaits his execution, and his godmother Aunt Emma implores Grant Wiggins to help restore Jefferson’s sense of self-worth, so that he might die with dignity.

It’s a powerful story, simply told. Several of the students in my group liked it best of all the novels we’ve read on this journey. They were stirred by the novel’s honest and direct portrayal of the segregated South, and the way the novel illustrates the insidious power of racism, not just in grand miscarriages of justice, but in the subtle nuances of everyday life (how for instance Aunt Emma, tired after a long wait to be received at the big house, is not offered a chair).

Ernest J. Gaines is in his mid 80s, a dignified man in a mobility chair with a brown felt beret on his head. He’s delightful, his seemingly gruff manner undermined by his quiet wit and the sparkle in his eye. We were met by his wife Dianne, who is entirely gracious and charming, and by his daughter Maria, and by Cheylon Woods, the director of his archives, who’d come from Lafayette to join us. (It was through Cheylon that I made the introduction).

Dianne took us first to the church that stands to the rear of their property, salvaged and relocated from the woodlands nearby.

This was where Ernest had his early schooling, and, in the novel, this is where Grant Wiggins teaches the local kids, and where he reflects on the repetitious cycle of black lives, the stagnant pace of improvement, expectations dashed by limited aspiration and opportunity. He watches the children laughing, chopping wood behind the schoolhouse, and he remembers his own contemporaries:

‘They had chopped wood here too; then they were gone. Gone to the fields, to the small towns, to the cities – where they died. There was always news coming back to the quarter about someone who had been killed or sent to prison for killing someone else: Snowball, stabbed to death at a nightclub in Port Allen; Claudee, killed by a woman in New Orleans; Smitty, sent to the State Penitentiary at Angola for manslaughter. And there were others that did not go anywhere but simply died slower.‘

Ernest and Dianne’s house stands as testament to the fact that such cycles can be broken, and that change can come, albeit incompletely. They designed and built the property from the ground up, with money from the sale of the movie rights to ‘A Lesson Before Dying’. It’s a lovely, comfortable home, filled with family photos and books, and the warmth of lives well lived.

Dianne Gaines, Ernest J. Gaines and Cheylon Woods

We sat at a walnut wood table, with Ernest at one end, low in his chair, talking slowly and reflectively in a deep Louisianan drawl. Dianne plied us with lemonade and teacakes and oatmeal cookies. And over the course of an hour or more we asked Ernest about his life and work.

Stasi asked how he began his career as a writer. He described how during his childhood in Pointe Coupée Parish, there had been no libraries available for African Americans children like him. On his arrival in California as a teenager,

“I had the choice of three places - I had the movies, the library and the YMCA. And I didn’t have any money so I couldn’t go to the movies. I went to the YMCA and was I was foolish enough to get in the boxing ring with a guy who just beat me up, you know? - so I thought I’d better go to the library. And it was there that I discovered books. Books and books and books and books. I didn’t know there were so many books in the world. So I started reading books.

“There weren’t hardly any books there about my people, my culture - but I read books by writers who wrote about rural life. I discovered 19th century Russian writers - Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy and others. They wrote about peasant life; I read that. But it was still not about me, it was not about my people. And it was then that I tried to write.”

He found inspiration in blues music, and in the shared recollections of friends, members like him of the African American diaspora. He wrote his first novel ‘Catherine Carmier’ in 1964, a Southern spin on Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’. He won a writing fellowship to Stanford, and his breakthrough novel - ‘The Autobiography of Miss Jean Pittman’ - followed in 1971.

He writes predominantly about the South in the ‘40s, a time when the social and racial construct conspired against black bodies and minds. Black bodies are imprisoned, executed, lynched. Black minds are kept in subservience through inadequate schooling and the steady erosion of self-respect. As Grant Wiggins explains to Jefferson in the novel,

“White people believe that they’re better than anyone else on earth – and that’s a myth. The last thing they ever want to see is a black man stand, and think, and show that common humanity that is in us all. It would destroy their myth. They would no longer have justification for having made us slaves and keeping us in the condition we are in.

“I want you to chip away that myth by standing.”

The day before our visit to Dr. Gaines, we’d walked up the drive of Parlange Plantation, one of the grand antebellum houses nearby. We’d been told that Miss Lucy, who lives in the house, doesn’t mind visitors taking photos, provided we kept our distance. So we approached, with a certain respectful deference. I recalled the sequence in the novel in which Aunt Emma and Grant Wiggins come to ask the white landowner, Henri Pichot, for permission to visit Jefferson. They must enter through the back door, and are kept waiting for over two hours. Grant Wiggins finds it hard to contain his resentment; he must force himself to address Henry Pichot as ‘Sir’. The very language he uses is laced with danger. He is, to white eyes, over-educated, and when he says “she doesn’t” rather than “she don’t”, it offends Pichot’s sense of racial superiority. Grant wonders:

‘Whether I should act like the teacher that I was, or like the n—r that I was supposed to be. To show too much intelligence would have been an insult to them. To show a lack of intelligence would have been a greater insult to me.’

(I’ve made an elision here. In the novel, Gaines spells out the 'n' word whenever appropriate, because this is how people spoke, and he strives for integrity as a writer. “I hope I’m honest”, he told us. I've elided it here because context is everything, and a blog is different to a novel).

Dr. Gaines described to us the case that inspired ‘A Lesson Before Dying’ - that of a 16 year old black kid, Willie Francis, arrested 1945 for the murder of a pharmacist in St Martinville.

Willie Francis, arrested in 1945, executed (after an earlier botched attempt) in 1947.

The parallels between Willie Francis and Jefferson aren’t in the details of the case; they’re in the innocence of the protagonist. Gaines wanted to write about a boy who knows about nothing but doing what he’s told to do, a boy who has never been shown love, who does not believe he is worthy of love. The offer of friendship Grant makes Jefferson is an offer of profound importance, because - and this is true for all of us - to accept real friendship we must have matured sufficiently to believe ourselves worthy of that gift.

'“Do you believe I’m your friend, Jefferson?” I asked him. “Do you believe I care about you?”.

He didn’t answer.'

Jefferson had been much in our thoughts the previous day. We’d visited the redbrick courthouse in New Roads, the setting in the novel for his trial and imprisonment.

I’d made arrangements with Sandra, who runs the Judge’s office, to see the courtroom. Sadly it has been extensively modernized and fails to capture much of the atmosphere of the book. But then, in conversation, Sandra happened to mention that the original cells still exist and are now used for storage. I asked if we might take a look. She called Tammy, one of the deputies, and with a handful of curious bailiffs in tow, amused by this gaggle of students on this strange ‘bookpacking’ pilgrimage, we made our way to the cells.

It was chilling. We rode in a rickety old elevator from the 1930s with a hinged cage door that once separated prisoners from guards. We emerged in a corridor painted an institutional grey-blue.

We pictured Grant Wiggins here, on his first visit to Jefferson’s cell.

‘There were six steps, then a landing, a sharp turn, and another six steps. Then we went through a heavy steel door to the area where the prisoners were quartered. The white prisoners were also on this floor, but in a separate section. I counted eight cells for black prisoners, with two bunks to each cell. Half of the cells were empty, the others had one or two prisoners. …

‘[Jefferson's] cell was roughly six by ten, with a metal bunk covered by a thin mattress and a woolen army blanket; a toilet without seat or toilet paper; a washbowl, brownish from residue and grime; a small metal shelf upon which was a pan, a tin cup, and a tablespoon. A single bulb hung over the center of the cell, and at the end opposite the door was a barred window, which looked out onto a sycamore tree behind the courthouse. I could see the sunlight on the upper leaves. But the window was too high to catch sight of any other buildings or the ground.’

We took photographs, and laughed nervously as Tammy activated the cell doors to imprison us inside. But Jefferson’s story had heightened our sensibility, and we were all genuinely disturbed, I think, by the perfunctory horror of this environment - the heavy locks, the door grilles, the peeling paint on the bars. One cell had a square of cement of a different texture to the rest; there was a hatch here once. This was a cell used for executions, and we were standing beneath the gallows.

The following day, I showed our photos to Ernest Gaines, and we talked about the contemporary incarceration crisis in America, and its racial dimension. He said, “This is a cliché, but it’s true - we have more young black men in jail than we have in college.”

The statistics make grim reading. The US has 5% percent of the world’s population but 25% of the world’s prisoners. African Americans are locked up at nearly six times the rate of whites. Louisiana locks up more people per capita than any other state of the Union, and Angola, the state penitentiary, is the largest maximum security prison in the nation. The average prison term at Angola is 93 years, and unless current laws change, 95% of the 5000-strong prison population in Angola will die there.

We reflected on the profound changes in American society over Ernest’s lifetime - and the fact that we could sit there, an ethnically mixed bunch of Americans (plus one Brit) in the comfortable home of a great African American man of letters. “We’ve come a great distance, because look at us,” Ernest said. “We’re sitting here. Nothing like this could have possibly happened fifty years ago.” Then he fixed us a wry smile, and said, “But you know the French saying - ‘the more things change, the more things remain the same’.”

In the novel, Grant rails against the stagnancy of the South and the slow pace of change. At the Christmas service, he notes:

‘The same people wore the same old clothes and sat in the same places. Next year it would be the same, and the year after that, the same again.’

Throughout this journey we’ve taken in Louisiana, we’ve driven through affluent white neighborhoods and seen the contrast with the more impoverished African American communities on the edges of each town. The rule isn’t hard and fast; there are plenty of poor whites, and plenty of affluent, middle class, professional African Americans. (And it’s not exclusively a Southern problem - far from it). But the simple fact remains: in communities and cities across America, a kind of segregation persists. As Faulkner put it in ‘Requiem for a Nun’, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past."

Ernest Gaines doesn’t offer solutions. As he put it, “I don’t know any laws that can change people’s hearts.” But at the core of his novels are stories of personal transformation and transcendence, and I find an optimism here. Jefferson finds his dignity; and Grant finds something more subtle, a spiritual understanding that belies his sceptical beliefs.

Morgan asked Dr. Gaines about his own spiritual journey, and he described his progression from ‘good Christian boy’ - baptized as a twelve-year-old child in the waters of the False River - to the theist he is today, of no particular denomination or religion, but rooted in his faith:

“I don’t only believe in God; I know there’s God.”

Grant questions the platitudes of the Minister, the Reverend Ambrose - but it is Ambrose, not Grant, who is there with Jefferson in the final moments of the novel. Grant lacks the strength to attend the execution, and he goes for a walk instead, musing on his own limitations as a teacher and as a man. But in his time with Jefferson, Grant has found a life force, which for lack of a better word he calls 'God' - something that joins us all, flawed as we are, in our universal journey, something which will hold Grant in the South, working with these children, doing the best he can.

‘Several feet away from where I sat under the tree was a hill of bull grass. … I probably would not have noticed it at all had not a butterfly, a yellow butterfly with dark spots like ink dots on its wings, not lit there. What had brought it there? … I watched it fly over the ditch and down into the quarter, I watched it until I could not see it anymore.

‘Yes, I told myself. It is finally over.’