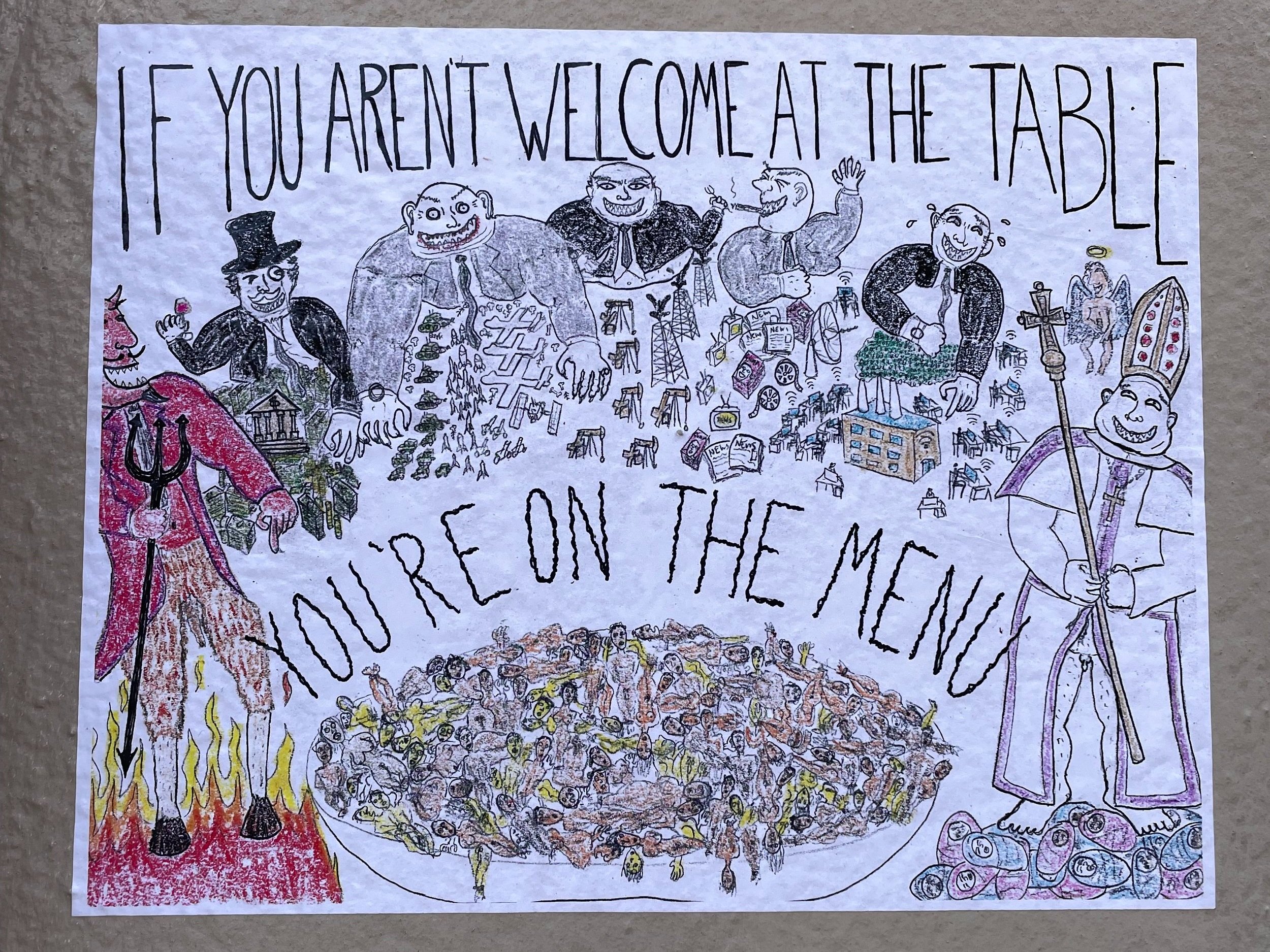

Photo Credit: Alice Gibson

Walking through the plantation was an unforgettable experience. We did a self-guided audiobook tour, following a set of carefully curated instructions which led us around the plantation. The tour began with a memorial, dedicated to the enslaved persons on the Whitney. From here, I already knew that this tour would be different from anything we’ve done so far. The message was clear: this plantation tour is to be focused on the lived experiences and realities of the individuals who lived on the plantation, rather than focusing on making a comfortable, easy to digest tour.

Following the memorial, we walked through the “titular” plantation elements. We passed under the enormous trees framing the luscious walkway, leading up to the home itself. Inside the home, we explored the amount of sheer luxury and leisure the slave owners held, with every facet being designed for their convenience and pleasure. Our tour truly began once we departed from the cool shade of the home, into the oppressive heat of the plantation grounds. The grounds were dotted with plenty of shade and benches for us to sit while listening to our audiobooks. However, I remained painfully reminded that this shade and rest granted to us was a privilege to enjoy, especially on these grounds.

““I had not then learned the measure of “man’s inhumanity to man,” nor to what limitless extent of wickedness he will go for the love of gain.” ”

From there, we toured the various structures built for enslaved individuals. These were buildings dedicated to cooking, laundry, and blacksmithing. There was even a plantation store, operational up til less than a century ago, designed to financially entrap enslaved individuals into a work structure post emancipation. Enormous sugar vats dotted the walkway, reminiscent of the treacherous conditions these individuals were subjected to for the sole purpose of turning a profit for their white owners. I was especially moved by the final exhibits of the tour, a selection of statues and memorials. Each of these immortalized nuanced elements of enslavement, such as rebellion and family dynamics. The final memorial was wall after wall after wall of thousands of inscribed names and written experiences of enslaved African Americans, one of the largest of its kind.

The Whitney is meticulously constructed and curated to remember this horrible chapter of history. However, remembrance and retelling is an unbelievably complex topic, one which we have discussed in depth. We had the incredible opportunity to chat with one of the interpreters of the Whitney. He revealed how his dedication to history and interpretation stemmed from his Native American heritage and their particular emphasis on oral storytelling. He explored the various forms of storytelling in relation to the Whitney and the American story of enslavement as a whole, also referencing a whole collection of “plantation movies”. This in depth analysis into the very nature of storytelling reminds me closely of something written by Sarah Broom in her memoir, The Yellow House.

““Who has the rights to the story of a place? Are these rights earned, bought, fought and died for? Or are they given? Are they automatic, like an assumption? Self-renewing? Are these rights a token of citizenship belonging to those who stay in the place or to those who leave and come back to it? Does the act of leaving relinquish one’s rights to the story of a place? Who stays gone? Who can afford to return?” ”

New Orleans is first and foremost a city obsessed about place. The French Quarter’s charm comes out of the history which runs its course through a place, prescribing it different architectural influences. The very city itself was erected to capitalize off of a strategically advantageous place. Enslaved individuals were forced to work and live in certain places, and even post emancipation were often trapped to those same places by an oppressive financial model. Place matters, particularly here in New Orleans.

So who deserves to tell the story of a place like the Whitney? Who should? I left the experience with these two questions ringing in my mind. As I continue to educate myself on the topic of race in historical and contemporary America, I am increasingly cognisant of just how difficult the answer is. The idea of a place in history, as we know it, regularly changes the more we discover and analyze. Even the plantation tour itself was different a few years ago, the exhibits being in opposite order. Such a minor change makes all the difference in the overall experience of somewhere like the Whitney. However, I am also aware that such a change would never be approved without extensive research, dialogue, and consultation by a team of experts. The efforts of these sorts of experts are then appreciated by people such as myself who see the evident result of their hard work. As our interpreter emphasized, a story remains alive as long as it is told, thought about, and interacted with.

““The mythology of New Orleans—that it is always the place for a good time; that its citizens are the happiest people alive, willing to smile, dance, cook, and entertain for you; that it is a progressive city open to whimsy and change—can sometimes suffocate the people who live and suffer under the place’s burden, burying them within layers and layers of signifiers, making it impossible to truly get at what is dysfunctional about the city.”

”

I finish my reflection in the contemporary New Orleans which I’ve been living in for the past couple weeks. The glamor and intrigue of this city is most definitely a “burden”, as Broom asserts. Enslavement and racism is a fundamental building block to this city. The business district which our hotel is was the epicenter of it all, home to slave pens and industry fueled by unpaid labor. Our exploration of the city made the effects of systemic racism all too clear: from widespread gentrification to the still economically disenfranchised neighborhoods from Hurricane Katrina. 1000 words is not even close to enough words to explore the hardships and atrocities, but it is definitely a start of a lifetime of learning and listening which I am eager to continue.