When I imagine Enjolras, I picture a constant breeze blowing through his golden hair. I see his hair billowing through some corner of the ABC Cafe, right by the “GIRLS KEEP OUT” sign. As he moves to the center of the room, I imagine him angling his head—that ridiculous, beautiful radical—not for stupid, vain, or girly reasons, but because he must. His golden locks wave like a flag in the wind, a flag that will signal the way to revolution. Therefore, he must look beautiful with his head angled just so—for the people! For Grantaire!

However, in my imaginings, the one thing I could not fathom was how Enjolras took himself and his golden hair so seriously. To me, he seemed smart enough to see how insular he was, and that the microcosm he dominated was simply that—a microcosm. I could not see why he was so intent on exclusivity. Wasn’t his revolution in the name of “the masses”? Why exclude them?

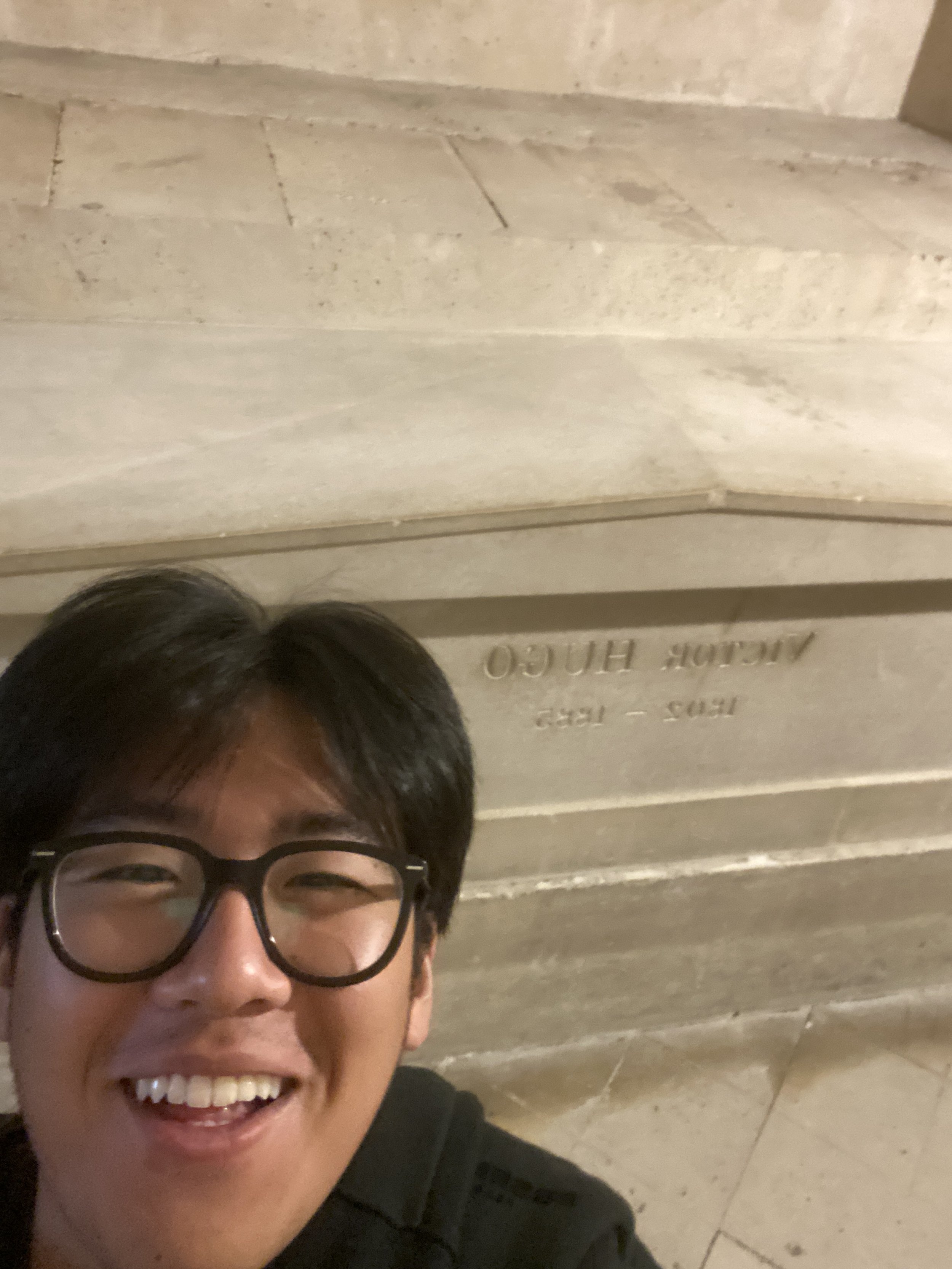

Even though I could not pronounce Enjolras’s name, I went to the Rue Sufflot in search of him. I called out On-shawl-ruh, and a golden head popped out of the window of a tiny cafe. I looked through the window into a cramped room, and I had my first answer: the masses simply would not have fit in The ABC Cafe. This is why “the Friends of the ABC were few in number. It was a secret society in embryo, we would say almost a clique, if cliques culminated in heroes” (584). The physical space necessitated a type of exclusion. In terms of physical room, there could not have comfortably been an ever-growing group. Especially because they are talking—talking about revolution, ideas, and life—the space is being filled in terms of breath and noise. The more people that breathe, the more heat fills the room. The more noise from talking, the less you can hear. To function as a group where ideas can be exchanged for a long period of time, there could not be a group large in number. Not to mention, there needed to be space for Enjolras’s hair.

However, this is not to justify the “GIRLS KEEP OUT” sign metaphorically posted up at the doorway. As The Friends of the ABC were a university group, I would draw a direct line from whom they exclude to whom the university excludes. Thus, I went to the Sorbonne!

I could not get into the Sorbonne. Entering into a university and seeing who is there, observing if people are friendly or competitive, and sensing if their noses are in books because they are precocious or passionate, felt essential to understanding Enjolras. But the walls of the Sorbonne are high.

Not one to appreciate a wall, I tried to google “how to enter into the university’s libraries as a non-student.” Oddly enough, my search autocorrected to “how to break into the Sorbonne,” which was truly, tragically out of my control and I simply had no choice but to pursue the route of a “break in.” Pursue I did! After an hour of clicking, I stumbled upon an intricate, secret map in the depths of the Sorbonne’s website. It showed me that if I take the back path, turn right, turn right four more times, and hop over the lava mote, I will reach a secret door with a sign that says “Nice try.”

I tell this story not because of its truth, but because it captures the energy of exclusivity around the University. In my difficulty accessing even the library, I saw Enjolras’s exclusivity in a new light. It seemed to me that there is a deep pride in exclusivity around any university space, and for Enjolras I saw the pride in exclusivity was also pride in purity. Exclusivity meant he was encouraged to weed out those not in line or likeness. He sought out “one true purity,” but as I walked around a university I could not even access, I saw who this excluded. As “most of the friends of the ABC were students who had an amiable understanding with a number of workers,” (584) it became clear to me that their exclusivity meant that university students of the 19th century—people who had access to certain ways of talking about revolution, time to spare where they could not be working, and were men—were an elite class often not grounded in reality. The guardedness of both of these spaces, the Sorbonne and The Friends of the ABC Cafe, made me question who “thought purity” was invented by, and whom it serves.

I understood that Enjolras was able to take himself beyond seriously because he saw the microcosm he was leading to be made up of the only people capable of being leaders, thinkers, and revolutionaries. He did not see it as a microcosm, but as a “clique made up of heroes.” I do not observe this as a way to dismiss their revolution—I am not anti-intellectualism, nor do I think their actions were purely selfish. I think the exchange of ideas is essential to social progress; my issue is the idea that these conversations can only be had in academic spaces. What would their revolution have been if it had begun not in The ABC Cafe, but in a factory? On the street? In a home? In a shop?

In university spaces, I often find there to be an emphasis on “belief.” What do people think, what do they read, what do they write? Enjolras is an “only son” and “well off” (585). He is approaching revolution with an air of belief—what does he think? What does he see? He deeply believes in the revolution. Yet, I observed within him and these spaces, a sense of belief rather than need. He does not need resources: food, water, or shelter. He needs a following, he needs belief. He wants to die for something grand bolstered by the purity of his thought. Without a revolution, his hair blows aimlessly in the wind. With a revolution, it is a glorious flag.

Their revolutionary thought is bolstered by space—they are made to believe their thoughts are deeply important and essential. They are institutionally backed by the university and are told they are capable of great thought. I do not make this observation to insinuate their observations or beliefs are not important, but rather to consider who universities continue to bolster and protect. It seems the “GIRLS KEEP OUT” sign is always posted but constantly evolving. Who loses out when learning is confined to certain years, certain spaces, and certain roles? What do we gain when we create physical spaces that necessitate inclusion? What is the difference between a microcosm and a community? How do we recalibrate to focus on bringing people in rather than leaving them out? How do we continue to cultivate revolutionary spaces?

Although the ABC Cafe is a highly imperfect model of exclusion, there is such a truth for me within it. It shows the importance of physical spaces where people feel safe to exchange ideas, change their way of thinking, and let these discussions lead to action. With one sentence, Marius allows himself to rethink his relationship with Napoleon. How many spaces have I been in where I witnessed someone change their thinking rather than defend it?

For me, Enjolras ultimately becomes a sort of cautionary tale. There are so many things I want to fight for with my community. I relate to the fervor of wanting change. I understand seeing what needs to be destroyed and reborn, and believing it can be done. The ability to fight is a sort of deep optimism and hope. What I don’t relate to, however, is Enjolras’s joyless pursuit of revolution. Hugo writes, “He was serious; he seemed unaware that there was on earth a creature called woman. He had only one passion: rightfulness. Only one thought: to remove any obstacle to it” (585). Enjolras was dead long before he was murdered. I do not want to be loveless in my pursuit of revolution. I do not want my passion to be “rightfulness” rather than “community.”

I wonder what the revolution would have been if Enjolras had taken himself and that golden hair less seriously. What would have been if the fierce leader fell in love—with a woman or community or dark hair? Who would have been let into the space? Who would have made it out alive?

Drawing by Vidya Iyer