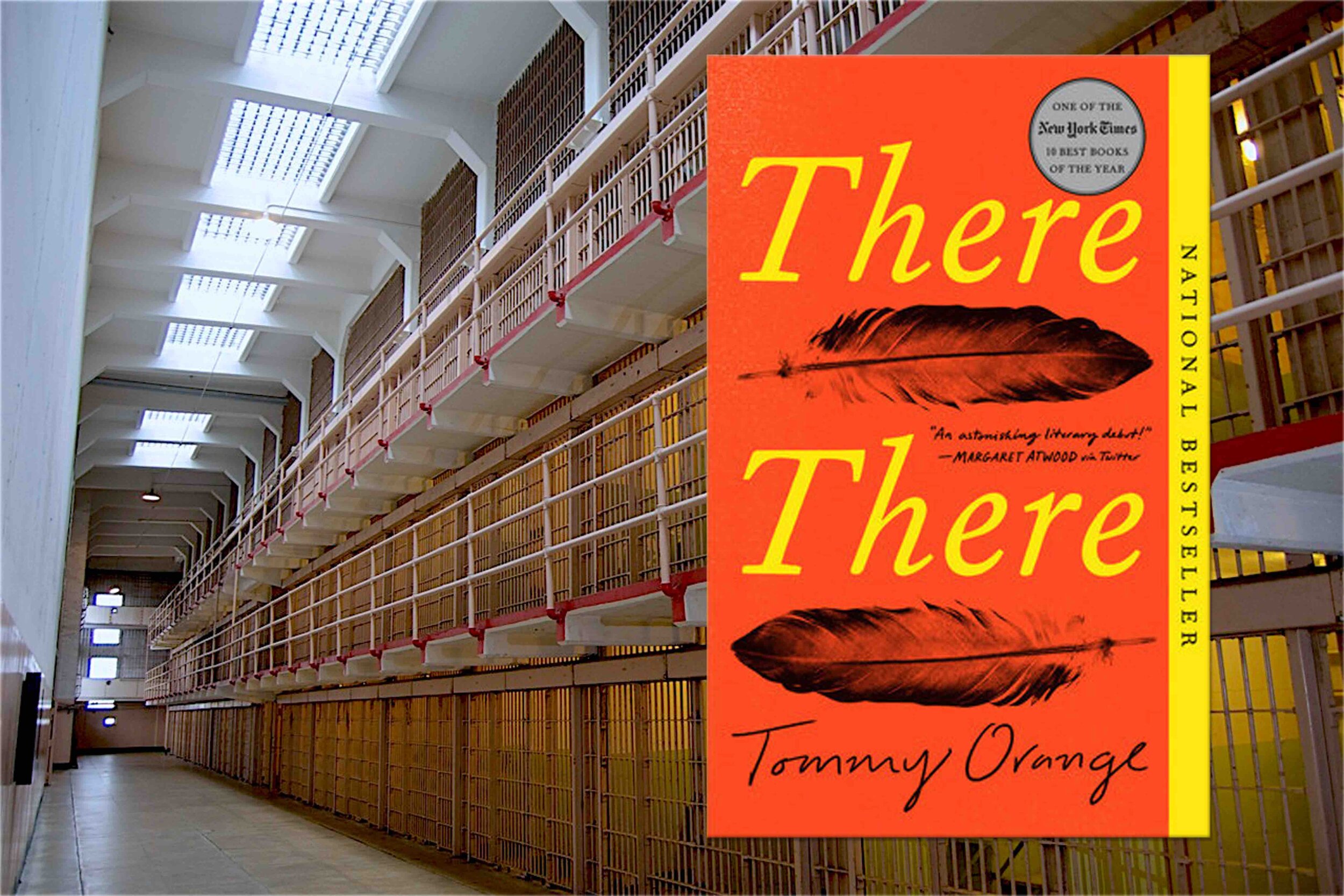

You can almost make out the blood-red Home of the Free if you squint hard enough to see past the prison walls. It’s Friday, November 22nd, six days before Thanksgiving and precisely 50 years since a bevy of Native Americans arrived on the former federal penitentiary “to celebrate not celebrating Thanksgiving.” I’m hardly listening to the boat’s intercom selling us $5 waters and instead find my gaze undulating between the San Francisco skyline and my well-worn copy of Tommy Orange’s There There.

Until just a few weeks prior I had only ever associated Alcatraz with Al Capone and Machine Gun Kelly; it was just an island in the Bay that people visit for a few hours each life to learn about the crime and punishment of 20th century America. Emphasis on visit. The Rock is a remarkably inhospitable place and anyone who’s been there can attest to its interminable accosting winds and shivering temperatures. No one stays there longer than they have to. Consequently, I’m shocked to see that our very first stop on the island is in front of decrepit scaffolding that proudly bears the inscription Indian Land. Where are we?

Native American stories are traditionally about an idyllic, nature-loving people — a reflection of the earthly traditions that were corrupted by the Evil of the West. In novels, the prototypical Indian is somewhere between a ritualistic shaman who can breathe life into being and the local drunkard who’s too stuck in their historical traditions to meaningfully contribute to society. In other words, we’ve been trained to imagine Native Americans as a people indelibly connected with the past, an almost fetishized rendition of the naturalized community who can teach the rest of us what it’s like to “live the simple life.”

Tommy Orange shatters this narrative with his debut novel There There. Set in Oakland circa 2018, the book is about being a Native American today. It’s about identity and your history and what to do when you never really learned your history because your mom has two jobs and you never met your Dad and even when you do see your mom she’s in a bad mood because you’re doing badly in school so who cares anyway.

“We came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range... the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls.”

Orange writes from the perspective of twelve different Natives whose shared history is almost overshadowed by their shared present. The novel begins with the musings of Tony Loneman, a young adult suffering from fetal alcohol syndrome who makes a living through the lucrative East Oakland drug exchange. We learn of the Oakland Coliseum’s forthcoming great Native American powwow, and how Octavio, an accomplice of Tony’s, thinks they can rob the place by using a plastic 3D-printed gun that can get through security. From there, we read of Dene Oxendene, a twenty-something who’s making a documentary about the perspectives of Native people in the Oakland area, and of Edwin Black, a biracial young man who earned a master’s degree in comparative Native American literature but struggled to find a job and is now somewhat addicted to the internet, not to mention the nine other Natives whose tales are just as layered as the aforementioned. These twelve stories interweave from the Native American occupation of Alcatraz to the violent, fast-paced life of East and Downtown Oakland. In other words, the novel exudes place in almost every scene, and as such, I arrive on Alcatraz island with an excitement to trace these characters’ steps in the physical world.

I climb off the ferry and walk toward a crowd of people listening to some middle-aged fellow talk about the day’s scheduled programming. Today happens to be almost exactly fifty years after the Native occupation of the island, a happy coincidence that further excites me for the day’s bookpacking. There There’s Opal Bear Shield and Jacquie Red Feather, aged twelve and eighteen respectively, are brought to Alcatraz by a desperate and frenzied mother in January of 1970. I recall Opal and Jacquie playing by the shore nearest the Golden Gate one evening, so so I dodge the crowd heading toward the prison and first climb a back road for the garden where they should have hung out. I stop by the shore and take in the view.

It’s actually quite a nice day, and I genuinely consider whether it was a good decision for their family to move to Alcatraz. But it was far too early to make a judgement about their experience, so I turn around and hike towards the penitentiary. About halfway along this walk I notice the water tower bearing Home of the Free has become uncomfortably visible. It seems ridiculous that any right-minded person would claim their agency by living on the United States’ most infamous prison grounds. Again, though, I try to withhold judgement until I hear the full story, contining into the cell block. I’m told by a volunteer that Alcatraz has some pretty phenomenal audio tours, so I grab a pair of headphones and walk around the prison. It’s pretty gloomy in here. The light barely enters through the ceiling windows and everything is colored cement gray. Even the prison yard, the island’s apogee of entertainment, is essentially a box of land. I look down at my book and see Opal’s mom explain that “everyone’s sleeping in cells. It’s warmer.” To her credit, perhaps there wasn’t much room for sleeping, but Alcatraz is a pretty big island. From the warden’s office to the officer quarters, there’s plenty of space to set up shop. Yet some of the Native Americans still chose to sleep in the United States’ most punitive prison cells.

““Me and Jacquie slept close, on Indian blankets, in that old jail cell across from our mom. Everything that made a sound in those cells echoed a hundred times over...” ”

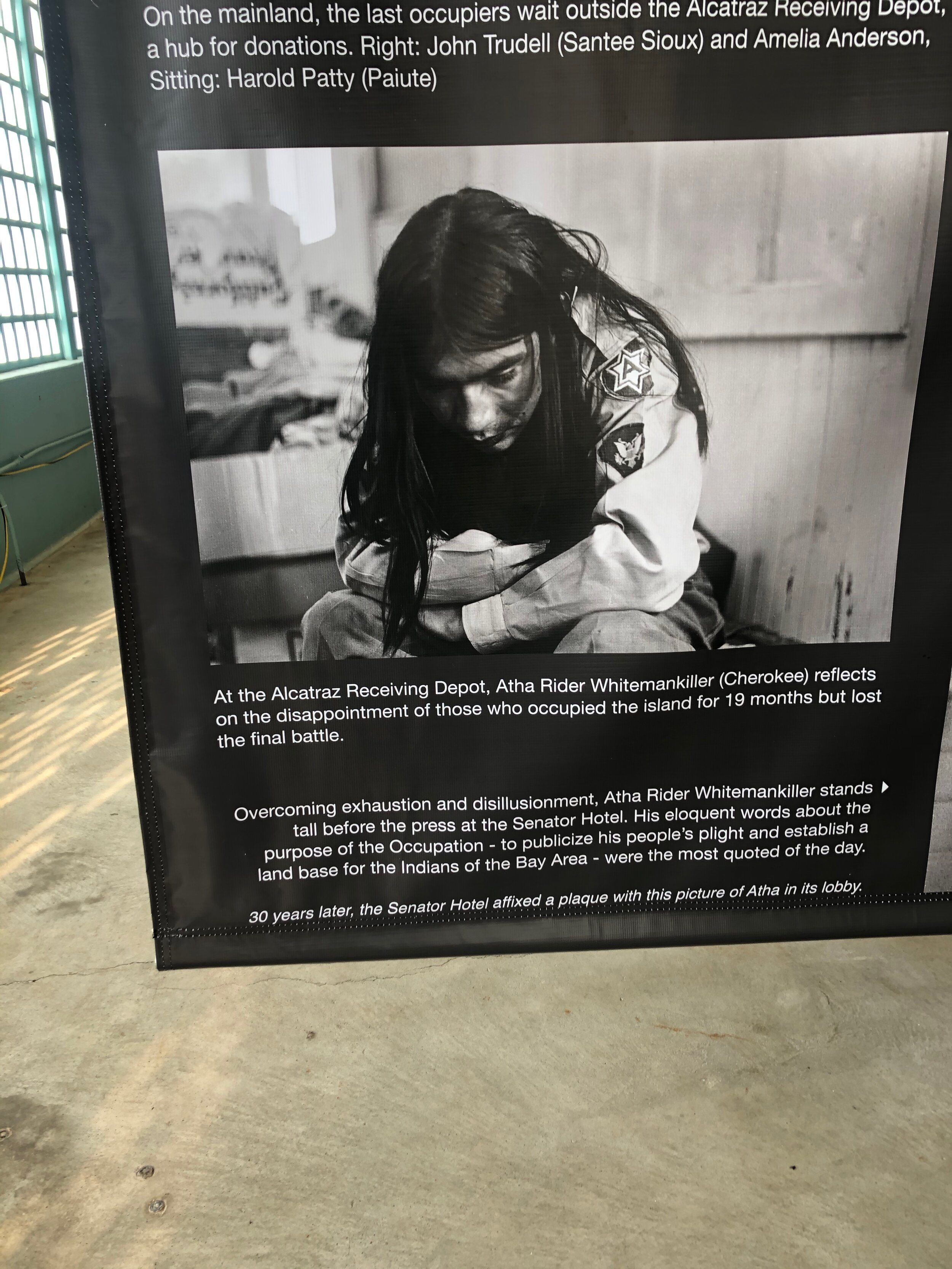

I found this photo hanging at different points around Alcatraz.

I run out of the prison toward the visitor center so I can make it to the Native American tribute by 11:30. The whole idea of living here is becoming less attractive by the minute. I arrive at the docks and am guided by that same middle-aged man from earlier toward a pseudo-auditorium. He starts describing the history of the occupation, how Natives from different tribes coalesced into the Indians of All Tribes and claimed the island as their own by arguing that the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which returned all retired federal land to the Natives who once occupied it, should apply to the now-closed Alcatraz penitentiary. Hundreds of people snuck onto the one-manned island and stayed put for nineteen months, but as time went on the island lost power, water, and food, and eventually the few remaining were compelled off the Rock via federal attrition.

We take a break from the history lesson and walk toward the exhibit that showcases pictures of Natives while living on the island. I ask the tour guide how he ended up here, and he says that he’s actually Native American himself and hails from South Central LA. Excited that his previous home coincides with my current one, I mention that I too live in South Central and have come to Alcatraz as part of a school project. He replies, “You’re not really from South Central. You’re from the bubble,” and he doesn’t seem particularly interested in my project. I realize that he may have grown up despising the “rich kids next door” at USC and immediately feel a tad uncomfortable. What can I say? Luckily, we arrive at the next stop after a few other pleasantries, and he then explains more about Native life on the island (as opposed to the survey-style history of it).

Look closely at his name. This is just one example.

We finally walk toward the art exhibit, and on the way there I hear a voice exclaim, “Is that Tommy Orange’s book?” I turn around to see the tour guide running toward me. Whatever tension was present just minutes before has dissolved completely and we’re immediately discussing the books’ characters. He then confesses that he’s only read the first few chapters but is afraid to finish the story because of the gun violence at the end. And to his credit, the ending of the story is altogether realistic and unsettling to say the least. Nevertheless, we’ve created a sense of mutual understanding, and he excitedly explains more about his life to me.

I arrive at the exhibit and continue inside solo, wandering from picture to picture of life on the Rock. I find a piece detailing the photography of UrbanRezLife, a woman in her fifties who lived on Alcatraz between the ages of eight and ten. There There’s Opal Bear Shield is similarly a woman who lived on Alcatraz around that age. In other words, they’re the same age, and from what I can tell through the exhibit, they share the same feisty disposition. I wonder if Tommy Orange modeled Opal off of this woman.

At any rate, I finish exploring the exhibit and head back towards the dock. From there I spend a few hours getting lunch before travelling from one city by the bay to the other. I have far too many places to explore upon arriving in Oakland and am not sure where to begin, so I get off the first freeway exit and hope that I’m near somewhere featured in the book. Luckily, I skim past the chapter where Dene Oxendene walks through West Oakland toward downtown, and that happens to be exactly where I am. I drive past “I-980 on the way into West Oakland” and find myself in front of the Ronald V. Dellums Federal Building complex. It’s right about here where Dene presents his preliminary work on documenting the experiences of urban Native Americans in hopes of earning a research grant.

I stop to watch the crowd buzz around me on this Friday afternoon, imagining Dene running down the street in his sweaty beanie before hurrying into his presentation. It’s in certain pockets of downtown like this that I begin to appreciate the relevancy of Orange’s text. West Oakland looks more run-down than the many pockets of South America I traveled to over the summer, but parts of downtown feature the Silicon Valley / LA esque all-lowercase-letter aesthetic. In other words, the gentrification is tangible, and it is only a few years old. Had the book only been released a couple years earlier, it would have missed the 2016-2017 wave of new-age renovations that have since pushed out thousands of indigenous Oaklanders (and Americans).

I head out of downtown toward the Coliseum as that part of Oakland is where the bulk of the story is set. Instead of taking the freeway, though, I follow the back roads like Orvil Red Feather and drive along 7th until it turns into 8th and then 12th and then finally runs by the Coliseum Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station. I stop midway on my drive at the Fruitvale BART station, for Dene, Bill and Thomas all have different scenes here. Interestingly enough, the Fruitvale station is fairly infamous in the Oakland area because a 22-year-old African American was essentially murdered in cold blood by the BART Police officer there in 2009. I wonder if that played a part in Orange’s design of the book’s settings. The walls nearby are covered with graffiti, and I’m genuinely impressed to see the surrounding area’s striking resemblance with Thomas Frank’s description of it in the novel:

“The train emerges, rises out of the underground tube in the Fruitvale district, over by that Burger King and the terrible pho place, where East Twelfth and International almost merge, where the graffitied apartment walls and abandoned houses, warehouses, and auto body shops appear, loom in the train window, stubbornly resist like deadweight all of Oakland’s new development. Just before the Fruitvale Station, you see that old brick church you always notice because of how run-down and abandoned it looks.”

Just like in downtown, the drive towards the Coliseum reveals stark contrasts between the affluent and poor. Within just a few blocks I see both antique Victorian homes and tent cities that give music festivals a run for their money.

Notice the contrast in the quality of the Victorian houses on the left…

I finally arrive outside the Coliseum BART station and soak in perhaps the most important location in the text. I’ve been coming to the Coliseum for years as a B-List A’s fan (I’m from San Jose), but whenever I do come it’s by car and involves me parking in the interior lot. I’ve never seen the entrance from the train station before. I opened to the final pages of the book and imagined the thousands of Native Americans streaming over the bridge above. Dene would be on the other side of the fence interviewing attendees, Orvil would be finding a sense of identity in dance, and Tony would be hidden in the crowd, contemplating his impossible situation before concluding that robbing the prize booth is his last and only option.

Staring at the familiar Coliseum of my childhood, I reflect on the differences between the path that has led me here and the paths that have led Orange’s characters here. With twelve different narrators, There There has some smart characters, some funny ones, and a few who get tragically caught in the inescapable cycle of addiction. The thread that ties them together is the direct influence that their indigenous history has on each of their lives. Whether characters are intimately aware of their Native heritage or only refer to themselves as a “pretendian”, their stories are each still the product of the stories that came before them.

“If you have the option to not think about or even consider history, whether you learned it right or not, or whether it even deserves consideration, that’s how you know you’re on board the ship that serves hors d’oeuvres and fluffs your pillows, while others are out at sea...”

I hope my Alcatraz tour guide finishes the novel. I hope people like Dene succeed in recording the stories of those who deserve to be heard. It’s documentarians like him that empower people to write their own narratives as an edifice supported by instead of collapsing under centuries of buried history. And when people own their story, they’re more comfortable in their own skin, they’re more understanding of the skin of others, and they might even be inspired to write a great next chapter. For “the world [is] made of stories, nothing else, just stories, and stories about stories.”