“We’re up against a mad machine, which mangles mountains and devours men. Somebody has to try to stop it. That’s us.”

I’ve been re-reading ‘Desert Solitaire’ - see here - and the experience has inspired me to try one of Edward Abbey’s novels, an eco-activist caper called ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’.

To be honest I didn’t realize that Abbey wrote fiction - but then last week I read an article online about the various attempts to turn ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ into a movie. First published in 1975, the novel clearly retains significant cult appeal; it has a jealous and protective fanbase none too pleased with the idea of Hollywood taming Abbey’s anarchic spirit.

From what I gathered from the article, it was about a group of eco-activists fighting corporate despoliation on the Arizona / Utah border, which (frankly) sounded all very ‘70s. But I figured - any novel written by the author of ‘Desert Solitaire’ has got to be worth a try. So I bought a copy, and spent some happy hours last week making a metaphorical tour of the Canyonlands in the company of Hayduke, Seldom Seem Smith, Bonnie Abbzug and Doc Sarvis - Abbey’s quartet of merry eco-saboteurs. And I’m glad I did - because as well as being a fun caper novel, ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ is a richly prescient account of the ongoing struggle for the soul of the West, as pertinent today as when it was first written. It’s not a patch on ‘Desert Solitaire’, and it has its flaws, but it’s provoking and worth the ride.

The novel is set in that part of the desert Southwest where Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado meet - the ‘Four Corners’ region. It’s an amazing place. I remember vividly a few years ago, on a road trip through the desert Southwest with my daughter Flo and my son Ollie, heading east from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon towards Page, AZ. The landscape was vermillion red, and the shadows of the late afternoon were lengthening, and the colours all around were saturated - the orange-red of the soil contrasting dramatically with the impossibly rich blue of the sky. We were dropping down across a desert plateau, a ridge of russet cliff guarding the road to the left, and all at once, around a blind corner, we found ourselves on a bridge over a deep ravine - a place called Marble Canyon - and there was the Colorado River, a hundred feet or more below us. We parked the car and doubled back across Navajo Bridge to marvel at the sight.

Reading ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ this week, early in the novel, I experienced that jolt of recognition as Hayduke stands on the same bridge and reflects on the same view - as described in Abbey’s sensational prose: “Marble Canyon gaped below, a black crevasse like an earthquake’s yawn zigzagging across the dun-colored desert.” Like an earthquake’s yawn - yes! Wow.

Hayduke is back from the Vietnam War, but only here, at Marble Canyon, does he feel truly at home. This, Abbey writes, is ‘the heartland of his heart’.

“It is the kind of land to cause horror and repugnance in the heart of the dirt farmer, stock raiser, land developer. There is no water; there is no soil; there is no grass; there are no trees except a few brave cottonwoods deep in the canyons. Nothing but skeleton rock, the skin of sand and dust, the silence, the space, the mountains beyond.”

Abbey loved this region. He was born in Pennsylvania but came west in his ’20s, and became the prophet of the desert, a latter-day Diogenes. If for no other reason, I recommend ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ for his extraordinary descriptions of the desert he knew so well - painstaking evocations of the locations he’d visited in those ‘seasons in the wilderness’ he describes in ‘Desert Solitaire’.

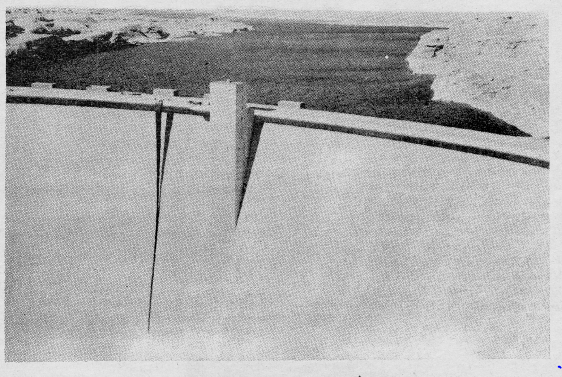

‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ opens at the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona - a controversial five-million-cubic-yard plug of concrete built in the ‘60s that bottles the Colorado, regulating its flow through the Grand Canyon, and which creates Lake Powell, one of the two great man made reservoirs that feed the thirsty cities of the lower basin (the other being Lake Mead). The novel opens with the Glen Canyon Bridge, running parallel to the dam, collapsing in a blast of dynamite - after which, in turn, we’re introduced to our four eco-conspirators, whose ultimate ambition (we’re told) is to blow up the dam itself.

They’re a motley gang of odd-balls, in the spirit of the kind of gonzo literature prevalent in the late ‘60s and ‘70s.

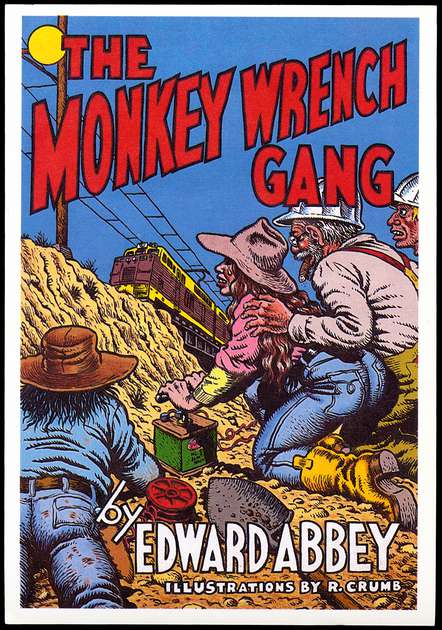

There’s ‘Doc’ Sarvis, an Albuquerque heart surgeon, who likes to set fire to billboards (‘everyone needs a hobby’); a ‘jack Mormon’ riverboat captain called Smith (‘Seldom Seen’ by his three wives scattered across Utah); George Washington Hayduke, hairy ex-Green Beret medic, who’s part Rambo, part Fabulous Furry Freak Brother (it makes absolute sense that one early edition of ‘The Monkey House Gang’ was illustrated by Robert Crumb); and finally, ‘the catalytic agent in this unprecipitated mélange’, a sexy feminist from the Bronx called Bonnie Abbzug - sexy, because however much Abbzug may be liberated, Abbey’s sexual politics isn’t even off first base. The novel suffers from a complacent sexism which is the norm in the Hunter S. Thompson / Thomas Pynchon pantheon. (It’s disappointing, but you just have to shove onwards, grateful that what’s good in the novel mostly outweighs the bad).

The four protagonists meet on a river boat trip south from Lee’s Ferry, on the Colorado River just west of Page, AZ. They bond over a mutual hatred of corporate power and the rape of the wilderness - and they vow to fight back.

As ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’, they spend the next three hundred pages blowing up bridges, tipping bulldozers into ravines, putting sand in engines and Karo syrup in fuel reservoirs. It’s all described in close detail, so much so that ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ has been hailed as a kind of anarchist manual, and Abbey was on FBI watch lists for much of his life.

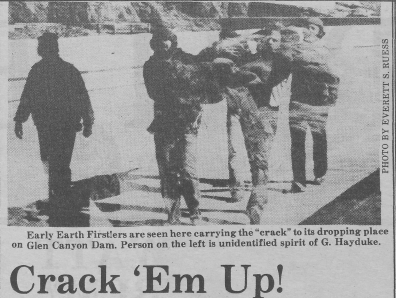

In 1981, inspired by the novel, a group of eco-activists called Earth First! began a modest campaign of sabotage inspired by the book; one of their more symbolic gestures was to unfurl a plastic banner down the face of Glen Canyon Dam, to suggest a crack in its concrete face - a direct reference to ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’.

Abbey himself never directly sanctioned violence; no one gets hurt, and the novel, as I’ve said, is a caper. The latter hundred pages or so is a chase sequence in which our protagonists are pursued by the bumbling representatives of Utah’s Search and Rescue, led by the Mormon ‘bishop’ J. Dudley Love, and it’s all great fun - akin to something like ‘Smokey and the Bandit’ in tone - in which we take delight in the crunch of metal as cars pile into each other and helicopters explode. And though it climaxes in a hail of gunfire, Hayduke re-emerges at the novel’s end. (No great spoiler, this - Abbey’s last novel is called ‘Hayduke Lives!’, a phrase that became an eco slogan). The point being, that Abbey wants passionately to alert us to the war that needs to be fought - but the novel remains a comedy. It’s an uneasy knife-edge, impossible to achieve in real life, and it begs the question - how far should we go in our Thoreauvian campaign of civil disobedience?

At times the novel becomes didactic, as yet another corporate crime is paraded before the reader - clear-cutting in the Kaibab forest, strip mining at Black Mesa, dams flooding natural habitats, ranching eroding and polluting the soil. ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ takes on each, and the reader is bludgeoned relentlessly with an understanding of one environmental concern after another. But the cumulative effect is powerful - an understanding of how the West has been raped over the decades (over the centuries, indeed) by a cabal of corporate and federal interests, a ‘kraken’ - as the novel puts it - of mining, ranching and lumber interests.

At one point, watching the harvesting of the forests on the north side of Grand Canyon, Bonnie asks Hayduke, don’t people need wood? Yes - and ditto water, and minerals, and fuel. But Hayduke puts up a spirited defense. “My job is to save the f***ing wilderness,” he says. “I don’t know anything else worth saving.”

The desert does not exist for us, Abbey argues. In ‘Desert Solitaire’ he writes, ‘There is no shortage of water in the desert’ - and what seems counterintuitive only makes sense when he adds the corollary, that ‘There is no lack of water here, unless you try to establish a city where no city should be.’

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread. A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying he principles of civilization itself.”

For Abbey, wilderness is intrinsic to our very nature - whether or not we experience it, whether or not we choose to visit it. Better, indeed, that we leave it alone; that we have no interaction with it, that it remains empty of any human presence or footprint. It’s a spiritual relationship in which the presence of the wilderness does not just feed the soul, it is intrinsic to the very existence of the soul. It’s a self-consciously Luddite trajectory, this; Abbey’s protagonists celebrate ’a great Englishman named Ned. Ned Ludd’, and Hayduke simply wants the wilderness back ‘as it was’. No roads, no settlements, no fencing, no exploitation of any kind.

My own sense, traveling around this desert region, is one of wonder, at the humans who have carved out a living in these inhospitable lands. Driving past the chemical plants on the edge of the great white mineral lakes on the road to Death Valley; or passing the massive wind farms in the Tehachapi Pass, and the solar fields at Primm, Nevada; or standing at the Hoover Dam looking down at this massive concrete endeavour - my response is one of awe, contemplating what we have made, what we have achieved, in taming this landscape.

I think of the labourers working in intense heat to carve out the roads through these forbidding desert plateaus and mountains, and rigging power lines, illuminating the desert, and constructing aqueducts to supply the cities - and I can’t avoid feeling respect and admiration for the scale of this human achievement. As Bonnie begrudgingly acknowledges at one point in the novel - ‘Now she knew what it took to build the Pyramids’.

Except, of course, that everything I’ve just described is anathema to an environmentalist. And, I get it - it’s the legacy of genocide, and it’s the legacy of political and corporate corruption on an epic scale, the product of the kind of graft which has become an American tradition. The West is a feudal land raped by corporate interests based in the coastal cities.

But my relationship with the West remains that of a human driving through it, amazed at the mere fact of our survival within it, and our limited attempt to benefit and profit by it. I can’t help but love this hardscrabble human history of the West - the stories of prospectors and school ma’ams, and the tough contemporary lives described in the stories of Annie Proulx and Claire Vaye Watkins. And for all the flaws in this very human history, I still find it inspiring.

I’m deeply empathetic to what Abbey describes. As I say, I get it. I’m challenged, profoundly, by this story of pillage and the part I play in it - my role as a consumer, doing my bit to destroy the planet - and as a visitor to the West of the worst sort, burning fuel in my air-conditioned car as I cruise the interstate, staying in corralled campsites and motels, marveling at the ‘wilderness’ as I hike manicured trails proscribed by the National Parks Service.

And yet, and yet.

At the end of ‘Desert Solitaire’, Abbey leaves Arches National Park, he puts back on his shirt and tie, he re-enters civilization. It’s a question, he reflects ultimately, of balance.

Read ’The Monkey Wrench Gang’ because it’s a laugh, and read it to be provoked - even if you have no intention yourself of grabbing a monkey wrench or of tipping the nearest bulldozer into a ravine. And read it to gain Abbey’s perspective on the wilderness, and the importance of preserving what little we have left - because although we might chose to ignore our national prophets, we need their provocation.