“In New Mexico he always awoke a young man. His first consciousness was a sense of the light dry wind blowing in through the windows, with the fragrance of hot sun and sage-brush and sweet clover; a wind that made one’s body feel light and one’s heart cry ‘To-day, to-day,’ like a child’s.”

We’re in Santa Fe, continuing our Bookpackers tour of Willa Cather’s New Mexico. I’m with our friends Stephen and Fiona, and yesterday evening we picked up Louise, my wife, from Albuquerque airport; she has bunked off work for a couple of days to join us on the Santa Fe leg of the journey.

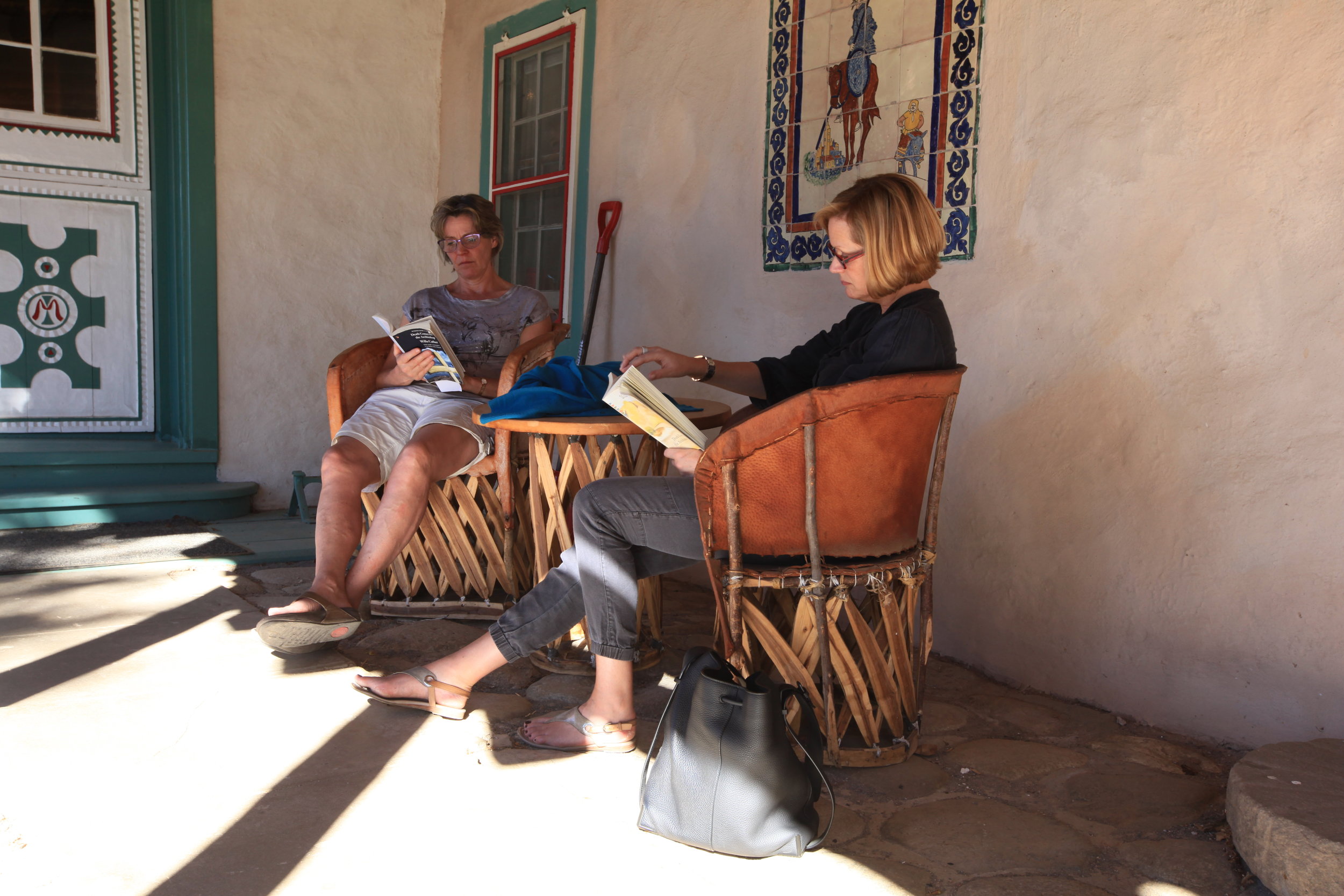

We each have a copy of ‘Death Comes for the Archbishop’, and we find pockets of time in which to lose ourselves in Willa Cather’s warm and inviting prose - sitting in cafés, sitting in the shade of Mission churches, sitting beneath the trees that Cather describes with such love - the flowering cherries and apricots that are in full bloom right now, and the cottonwoods that stand, stark and twisting, against the piercing blue sky. We’re not pushing ourselves to notch up the sights; rather, we’re living as Cather’s hero Bishop Latour lived: slowly, contemplatively, finding the joy in the gaps between things rather than rushing to the next moment of significance.

Willa Cather first visited New Mexico in the years before WW1. She was brought up in Nebraska (she’s best known as a novelist of the Plains), but her brother Douglas worked on the railroads in Arizona and she traveled extensively through the Hispanic desert regions of the Southwest. I’ve read ‘My Ántonia’, her novel describing a Bohemian immigrant family eking out a living on the western Nebraskan prairie, and ‘A Lost Lady’, set in a railway town in eastern Colorado - both wonderful - but ‘Death Comes for the Archbishop’ is something special. It’s such a surprising book, this fish-out-of-water story of a refined French churchman in a rough-edged world. It’s full of funny characters and quirky incident - but what speaks most loudly (especially in this time of division) is the depth of compassion Cather captures, and the spirit of grace and humanity with which she draws together the different cultures in the story.

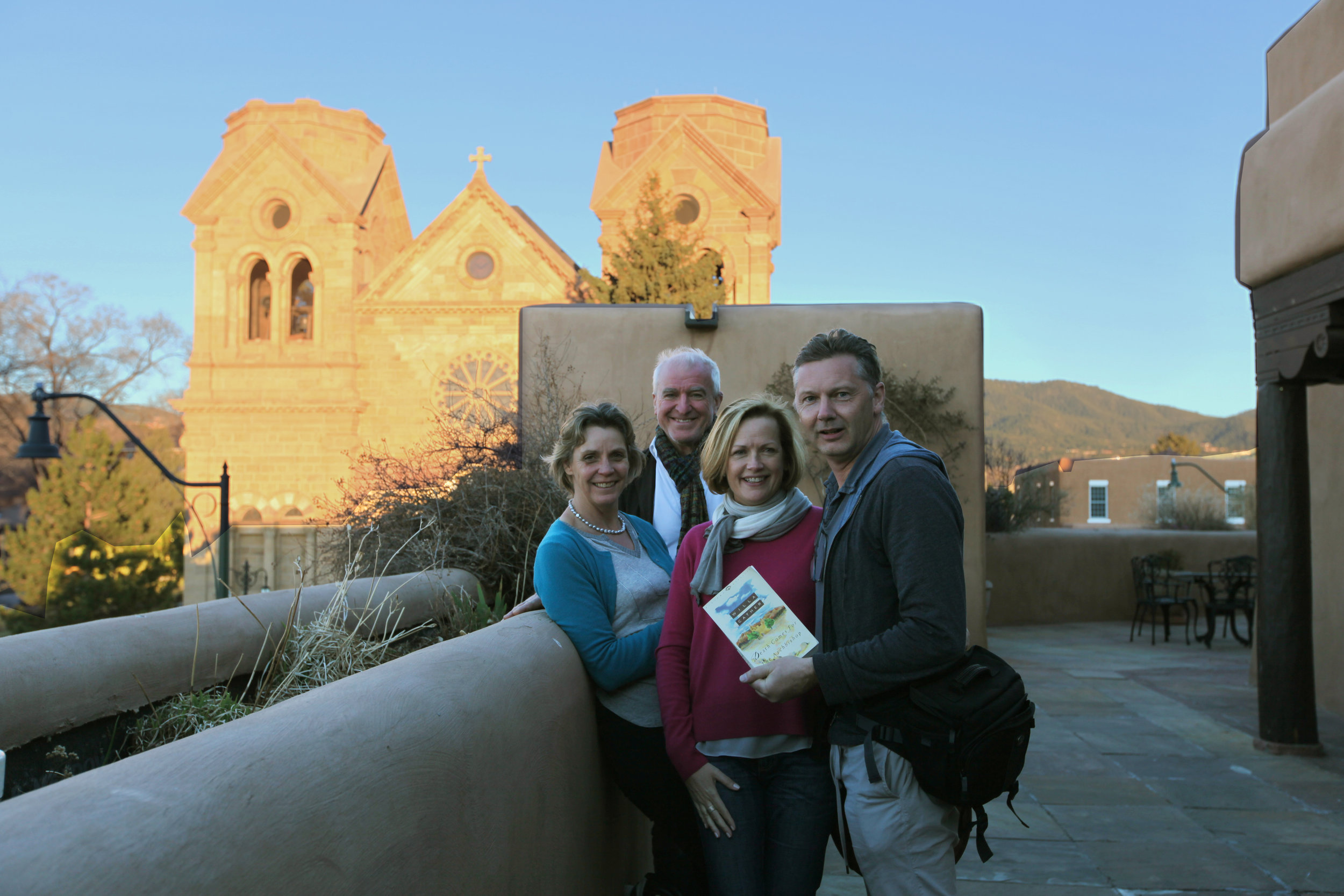

Bishop Latour, her hero, is based on a real man, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, who was Bishop and then Archbishop of New Mexico from 1850 into the 1880s. His statue stands in front of the Cathedral he built, just to the east of the downtown plaza in Santa Fe, a lovely piece of Romanesque in soft yellow sandstone that complements the adobe buildings all around.

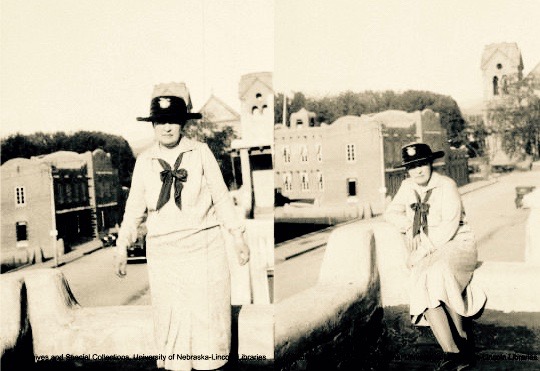

So this bookpackers tour is a journey in the footsteps of Bishop Latour - but also of his real-life counterpart Bishop Lamy, and of Cather herself, whose haunts here in Santa Fe we're visiting. There’s a photo of her taken in the mid-1920s by her companion and editor, Edith Lewis; she’s standing on the roof of the Hotel La Fonda, with Lamy’s Cathedral in the background. Gabriel, the very helpful day-manager of the La Fonda, took us up to the hotel’s terrace to take a matching shot.

It was at the Hotel La Fonda, apparently, that Cather had the idea of writing the novel. She’d returned to New Mexico at the invitation of D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda, who were living in Taos, north of Santa Fe.

Taos in the '20s was home to a colony of artists and writers, and both Santa Fe and Taos retain that artistic feel. We had a happy time pottering in the various craft shops and galleries that line the plaza, and we visited the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. More interesting from a ‘bookpacker’ perspective was the ‘Southwest Sampler’ gallery in the New Mexico Museum of Art, a perfectly-sized selection of paintings by American artists working in Taos and Santa Fe in the 1920s and '30s - many of whom Cather probably met on her travels here.

We drove north of Santa Fe, taking the old highway to Taos through the Truchas mountains, imagining Bishop Latour and his childhood friend and Vicar General, Father Vaillant, hacking this tough terrain on their mules Angelica and Contento. The landscape was wonderful, and just as Cather described: red conical hills ‘the shape of Mexican ovens’, the rich blues of distant mountains, creeks full of sedge, willows yellow-green in their first foliage.

In Truchas, we recalled the marvelously gothic story in which Latour and Vaillant encounter the gruesome Wyoming hunter Buck Scales, and are saved by his wife Magdalena - whom they then rescue in turn. This is the joy of bookpacking, traveling through a landscape populated by characters from a novel, both real and imaginary, each incident adding flavour and depth and insight to the journey.

We visited Chimayo, the place of healing mentioned by Sister Consolata in Laguna Pueblo. We weren’t sure what to expect of Chimayo, but it proved to be extraordinary. It’s described as ‘the Lourdes of America’. The exterior fence is lined with crosses, brought here by penitents who still come regularly in pilgrimage. The annex of the Sanctuary Church housing the ‘holy dirt’ is lined with crutches left by those who've experienced healing. It’s easy to be skeptical in these kinds of places, but I found the simplicity of faith here uplifting. And even the most hardened cynic would surely delight in the quality of Christian folk art in the nave of the Sanctuary Church. I’ve rarely seen anything so beautiful. The walls are lined with carvings and paintings of saints and angels and scenes of the crucifixion, artifacts from America’s earliest colonial period. I sat in happy contemplation, transported back to a frontier Hispanic world in which faith was primal and visceral, connected to the seasons and the cycles of life and death.

From Chimayo, we drove to Taos, where Bishop Latour comes in the novel to deal with the rogue Padre Martinez. Martinez is a real character. A Catholic priest, he presided over Taos in the decades before US annexation, and there’s a statue to him in Taos’ main plaza. He's remembered here with pride - a contrast to the caricature presented in the novel. Cather describes him accumulating wives and property and bending the laws of the Church to suit his purpose, and Latour comes here to pull him into line. As the novel puts it, ‘Father Latour judged that the day of lawless personal power was almost over, even on the frontier’.

Taos still has the feel of a frontier town. Kit Carson’s house - now a museum - stands just off the dusty main street. We pictured how this place must have seemed to Willa Cather, visiting Taos in the 1920s, when horses and mules still outnumbered cars. We loved the vibrancy of Taos, the distinctive aquamarine blue of the woodwork contrasting with the adobe walls in the spring sunlight.

One final destination to mention before I wrap up. On the late afternoon of our visit to Taos, we drove north east of the town to the lodge once owned by Mabel Dodge Luhan, New York society heiress and literary patron. It was Mabel that invited D.H. Lawrence to Taos; she gave him and Freida a ranch in exchange for the manuscript of ‘Sons and Lovers’. When Lawrence invited Willa Cather to return here, she spent a couple of weeks at Mabel’s lodge. Mabel’s fourth husband, Tony Luhan, was a Native American who’d seduced Mabel, setting up a tepee in the yard and drumming to entice her outside. Mabel sent her third husband packing and married Tony, her ‘mountain’, and it was Tony Luhan who gave Willa and Edith rides through the desert, answering Willa’s questions about Native culture and traditions, telling stories of the region and the vibrant personalities who lived there, stories that all made their way into the novel.

I love the image of Willa and Edith bouncing along in the rear seat of a pony trap, with Tony up front under his purple Indian blanket, his silver bracelets jangling, navigating through the sagebrush and juniper.

The Lodge was once owned by Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher who established the literary prize that Willa herself won, in 1923. Later, Dennis Hopper stayed here, when he was filming ‘Easy Rider’, and he bought the house and owned it for a few years - he called it the ‘Mud House’. Now it’s a guest house run by volunteers, and very charming it is too, with comfy rooms with pictures of the wonderfully bohemian Mabel Dodge Luhan on the walls. Many thanks to Carol and Josephine who gave us tea and answered our questions and allowed us to sit and read the final chapters of ‘Death Comes for the Archbishop’ on the verandah - on the wall of which was an image in tile of Don Quixote, as if in testament to the quixotic nature of this ‘bookpacking’ experience.