“Above all, there was understanding. She felt as if a mist had been lifted from her eyes, enabling her to look upon and comprehend the significance of life, that monster made up of beauty and brutality. ”

As someone who is naturally reflective and analytical with a touch of perfectionist, it is incredible to reflect on this trip. I continuously forget that this was a class because I learned so much about the world and about myself, about other people in Louisiana and about my fellow bookpackers. I learned about humanity, about the value of education, about moving on from one day to the next. My birthday is coming up, and another year means another reflection on my life over the past year. This bookpacking excursion was the perfect finishing touch to my year—it put the majority of my past year into perspective while also teaching me so much more. This past month has honestly been one of my most favorite months of the past twelve.

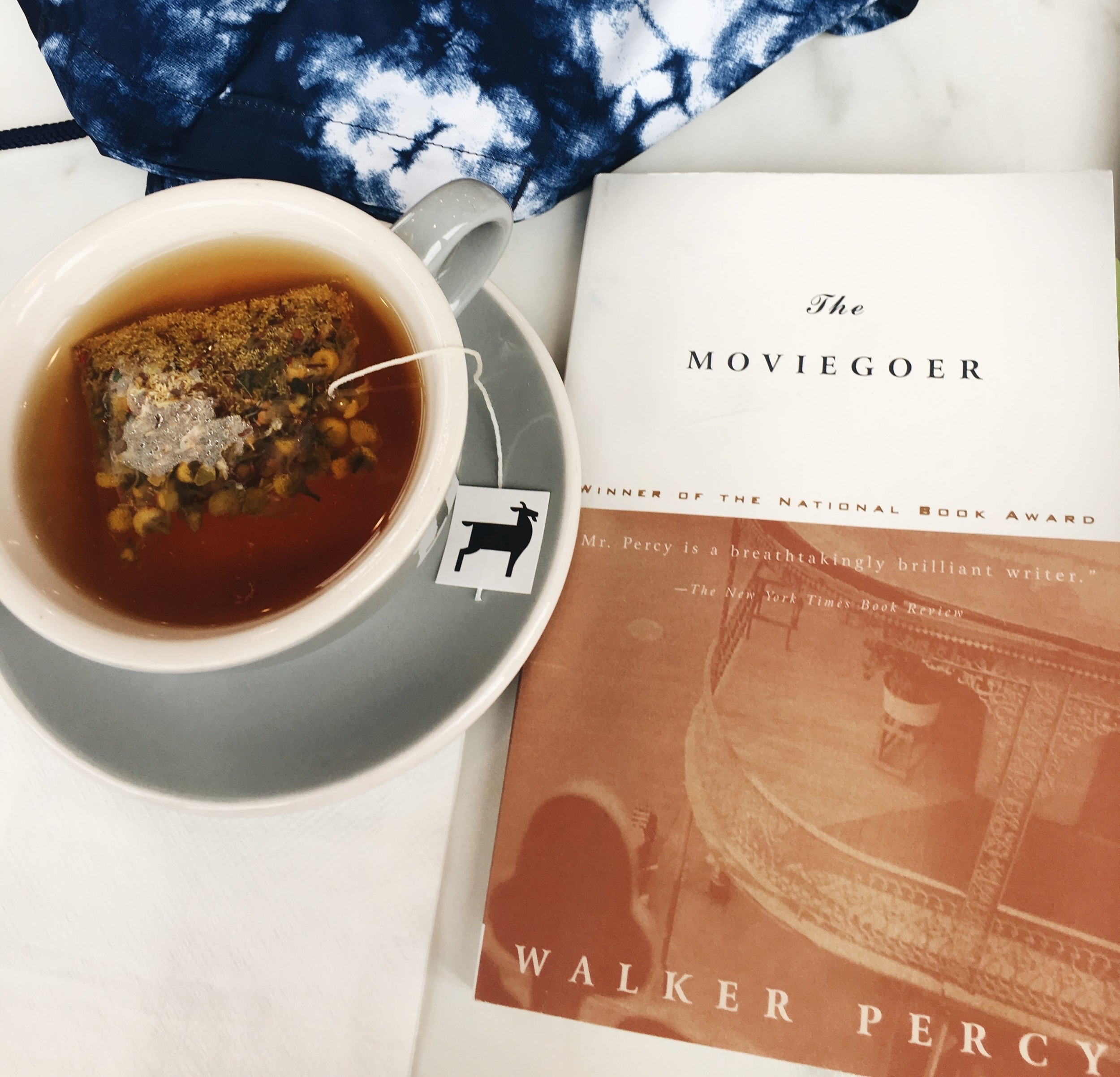

In the hope that I don’t get too philosophical or sappy, I’ve chosen some of my favorite lines that I underlined while reading the books for this class. When I read books, I actively read and mark up the pages of a book in two different ways: for educational purposes, for future papers, etc., and then for my own enjoyment. I read somewhat quickly so I tend to underline things I love without really soaking it all in, but now that I’ve flipped through all the books we have read over the course of the semester I found a common thread in what I enjoyed most. Virtually everything I underlined and starred as being important to me had to do with life, life compared to death, and, more generally, existence. A great number of characters, if not all the main characters, in the books we’ve read have gone through awakenings where they learn more about themselves and their lives. I’d say I was right there alongside with them.

While we didn’t stay in New Orleans for the entire trip, we did spend a good amount of time in the city in the first weeks of our time in Louisiana. One of my favorite lines from Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, a book about a vampire trying to find his place in the world and, more specifically, in New Orleans, Louis the vampire makes this comment when he looks back at his life:

“But all during these years I had a vague persistent desire to return to New Orleans. I never forgot New Orleans.”

This goes for New Orleans and for the experience as a whole, but so many incredible memories and friendships were made over these past weeks and I can’t imagine ever forgetting them.

Tim Gautreaux writes about life as a Creole versus stereotypical Southern life in his short story entitled “Floyd’s Girl”. Food and religion is extremely important to those with French backgrounds, and, after a young girl has been pulled away from her father, her grandmother exclaims of her granddaughter that:

“Living without her food would be like losing God, her unique meal.”

In context, the Creole grandmother is appalled that her granddaughter who has almost been kidnapped by her birth mother’s boyfriend will have to live in a place like Texas without her comfort food and without Catholicism. While the religious aspect of this quote is too complex for me to cover in one blog post, I can definitely touch on the food aspect of the quote. introduced me to so many amazing foods and restaurants. I never thought I would try oysters or liver pate, but I tried foods for the first time during these past weeks we have spent in Louisiana. I never thought I would be able to tell New Orleans locals that I have been to iconic restaurants such as Antoine’s, Commander’s Palace or Napoleon House, but I have and now have the power to give restaurant recommendations for New Orleans. I could not have gotten through this time without food, and especially all the amazing foods we’ve been so fortunate to get a taste of throughout our time.

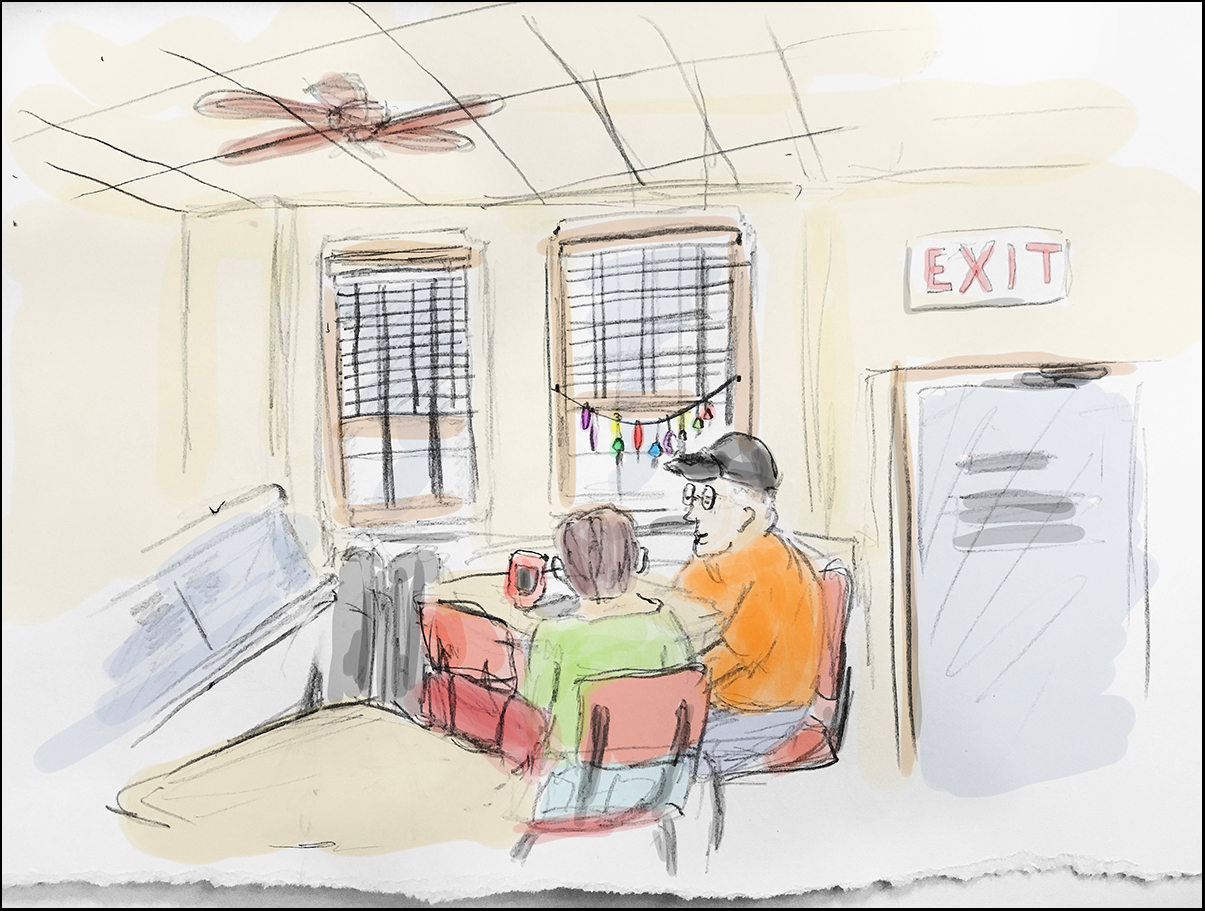

This bookpacking excursion has been crazy, relaxing, eye-opening and educational all at once, and I think that that is the joy of reading books in the location where they take place. When I was younger, I always imagined the books I read coming to life and thought how cool it would be to see the world on the page pop up in front of me as a hologram. While this world does not have the technology to really do that, bookpacking is more or less the same thing—it’s also more real and authentic compared to a hologram.

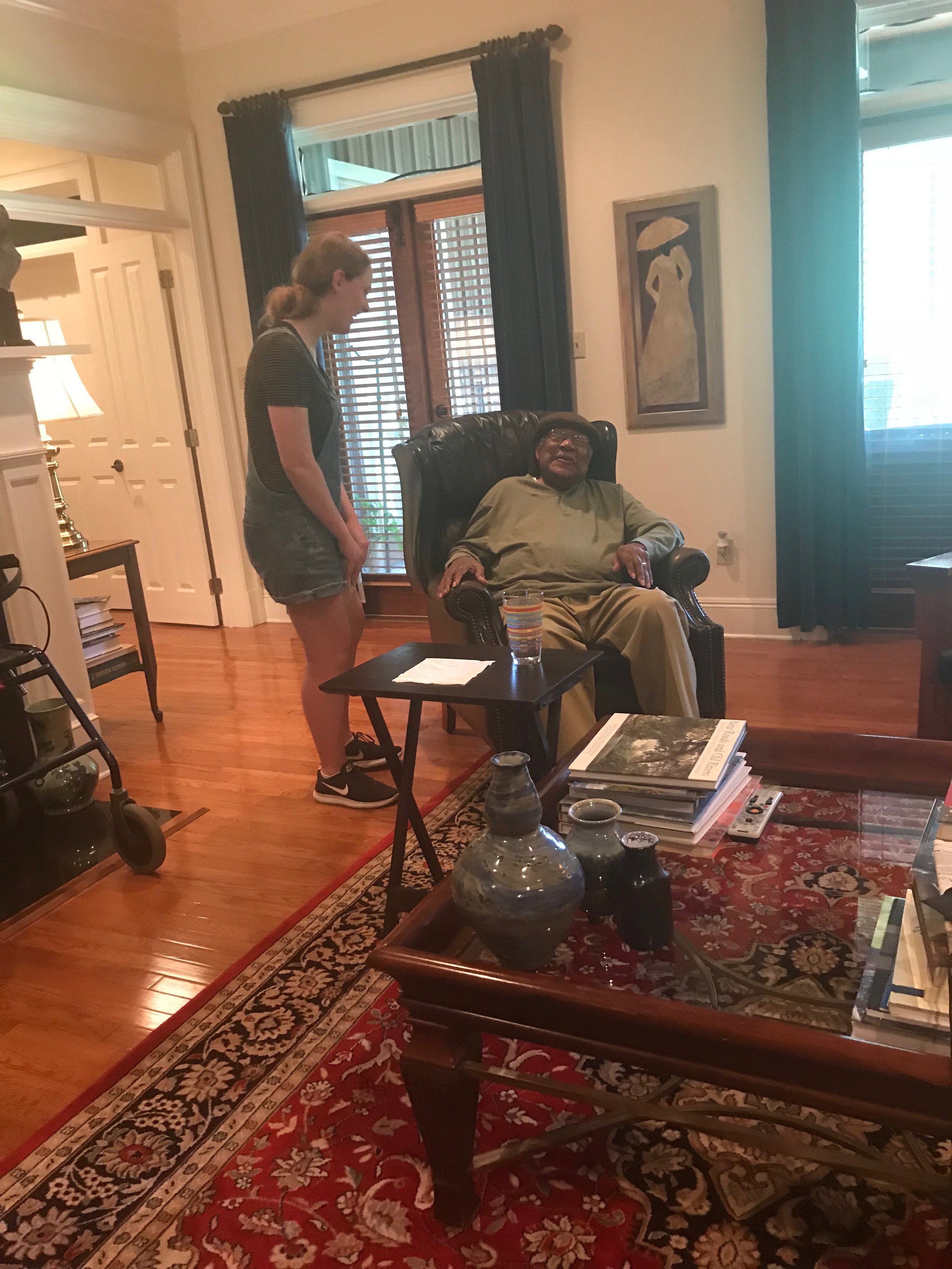

I certainly will not forget New Orleans or all the wonderful places we were able to travel to in Louisiana. This experience was truly an experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful I was able to be a part of it. With the chaos of school ending as well as the chaos of my own life, this class, this trip, was a much-needed awakening. In the weeks prior to flying out to New Orleans with 11 complete strangers I was stressed out and not in the greatest of spirits. Next year I will be a senior in college, which is something I still am having trouble fathoming, but I feel as if I have been confused about what my life is going to be like over these next pivotal few years. But after having spent these last three and a half weeks with an amazing group of people, I have learned a lot about myself, have become somewhat less stressed out since those very first days of the experience and have a more positive outlook on life in general. Sure, I learned about Louisiana, about the culture and history of this special place in the United States, learned about the people who inhabit it and have read and experienced what I have read in a way I could never imagine. More than anything, however, I was inspired in some way by every single person on this trip and now feel as if I am starting to find my place in this world.

“I don’t know when I’m going to die, Jefferson. Maybe tomorrow, maybe next week, maybe today. That’s why I try to live as well as I can every day and not hurt people. Especially people who love me, people who have done so much for me, people who have sacrificed for me. I don’t want to hurt those people. I want to help those people as much as I can.”