A vibrant city torn between vice and virtue, built on blood and drenched in decadence – this is the New Orleans that persists today, the way it always has been. There is first the gentile tradition of hospitality and faux nobility – of opulence, grace, and elegant architecture – but there is also a persistent impression of pain upon its people, which stems from successive transitions of cultural dominance, the inescapable history of enslavement, and the fatally unforgiving results of a tempestuous climate. One must first understand the significance and complex interplay of these elements in order to grasp the city’s unique spiritual prevalence and the conditions which bred a people’s desire to escape into something else – something otherworldly perhaps.

Upon arrival, there is an immediate charm to the city and its residents. The incredible preservation of antiquity and a sense of sunny disposition makes it almost impossible to believe that the city was settled upon a swamp and since been repeatedly ravaged by hurricanes. Add to this turmoil the clash of culture and class, the mixture of religion and mysticism, and the fear of ravenous creatures that infest the waters, and you’ve created the perfect playground for supernatural beings to materialize and ghastly demons to prey.

Enter Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire, a gothic horror novel that chronicles the undead life of Louis de Pointe du Lac, whose vampire journey starts in late 18th-century Creole New Orleans. Anne Rice is a wonderfully descriptive author who often overindulges her readers in the scenery and the people that inhabit her stories, but being able to actually stroll the streets that bleed from the novel’s pages makes for an especially thrilling read. The ability to truly envision characters in a space, to imagine the world they walked in past mine, is an experience unparalleled.

“…let me describe New Orleans, as it was then, and as it was to become… It was filled not only with the French and Spanish of all classes who had formed in part its peculiar aristocracy, but later immigrants of all kinds… Then there were not only the black slaves, yet homogenized and fantastical… but the great growing class of free people of color, those marvelous people of our mixed blood…who produced a magnificent set of craftsmen, artists, poets, and renowned feminine beauty. And then there were the Indians… the people of the port, the sailors of the ships… [and then came] the Americans, who build the city up river from the old French Quarter with magnificent Grecian houses which gleamed in the moonlight like temples… This was New Orleans, a magical and magnificent place to live.

”

It is the lingering influence of these people that can be found at every street corner, permeating every structure with its own story, and distinguishing districts with distinct flavors, that drew me to this city.

The French Quarter was our first point of interest; intricate, lovely, posh – the strong stench of tortured artiste brewing. Its otherwise quaint appearance is overpowered by bars, balcony cafés, music and art studios, and, unfortunately, tourist traps. The locals are friendly and happy to talk – a waitress has no problem sitting on our lap or sharing our fries, and a stranger happily offers a caricature in exchange for a cigarette. The camaraderie can be startling to those unaccustomed to these candidly welcoming transgressions, but they are mostly innocent.

The relative openness of Creole and Cajun culture presented in The Awakening soon blends with the abstracted occult of Interview with a Vampire. Brimming beneath the surface, chipping away at its beauty, there is a much darker side to the city. Gentility quickly gives way to some uncanny characters, and the quarter breathes new, vehement life at night. The chronically poor and afflicted majority created a need for release, and so arose vice and superstition. It did not take long get a taste for the city’s eclectic atmosphere, but New Orleans goes beyond the cheap thrill of a tourist’s séance or the stories of haunted hotels. It’s more than palm readers and psychics, scammers, vagrants, and fanatics in costume on Bourbon St. (catch demonic cat-man outside the bar on weekends). These people are not just here for show – for better or worse, some are thoroughly infused with this chaotic energy.

Apple-Jax, a pigeon-dove that blessed Maria at a corner store, stands out amongst these experiences. We had noticed him perched upon a man’s shoulder, tattered clothes and skull cane in hand, when we walked into the store to buy stamps for post-cards. While in line, he at once he flew to Maria’s unsuspecting shoulder, and the man quickly came over to us claiming she had been chosen that night for the energy she exudes. We chatted with him briefly until his friend approached – on the way out we could hear them talking about a third accomplice: “Parrot Man.”

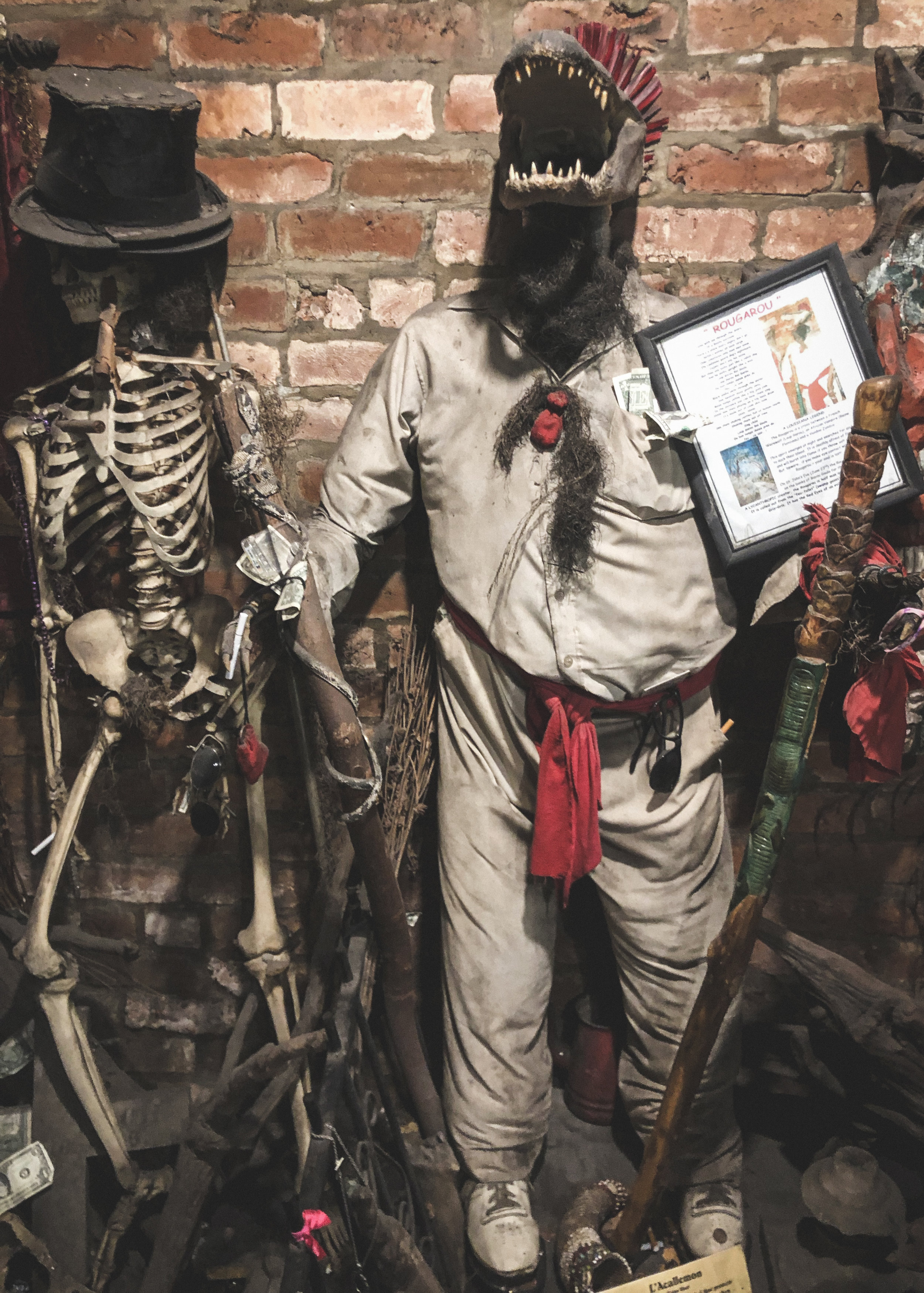

There is of course also the prevalence of New Orleans Voodoo – a syncretized version of Catholic Creole practices mixed with African-based folkway spirituality rooted in the practice of Vodun (from which springs Haitian Vodou and Deep Southern Hoodoo). A trip to the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum was both deeply informative and eerie – the woman at the entrance was particularly suspicious of my entering the museum as part of the group, cautious of my energy and quite foreboding when I had later lost myself from the group. I was pleased to discover however that most Voodoo is not used for malevolent hexing the way pop culture would lead you to believe, but rather for potions of love, luck, and spiritual healing.

While it is not the final resting place of Marie Laveau, the mother of Voodoo, we did of course visit the New Orleans Lafayette Cemetery to further our historical understanding and spiritual journey. Home to the supposed inspiration for Lestat’s tomb in Interview with a Vampire, the cemetery was magnificent to see in person, stacked with rows and rows of raised tombs that range in date of burial from the early 19th-century to the present day. An immigrant myself who has moved around many times in life already, it almost took my breath away to realize I stood where families have lived and died for generations. What’s cool though is that the cemetery is but a short walk from Anne Rice’s house, a reminder clearly of just how close to home she got her inspiration from.

So far, New Orleans has proven very dynamic, constantly at odds with itself in regards to upholding values and falling prey to temptation. The city’s mystical tendencies allow one to easily get lost exploring both facets of themselves – a freedom which seeks to open a door towards a metaphysical journey. It probably continues to inspire creators and innovators musicians just as often as it snatches them up and spits them out whole, yet it has a lot to teach us, about the world and about ourselves. To take away a lesson from Lestat:

““Evil is always possible. And goodness is eternally difficult.”

”

““MARIE LAVEAU”

Now there lived a conjuring lady, not long ago

in New Orleans, Louisiana, named Marie Laveau

Believe it or not, strange as it seems

She made a fortune selling Voodoo

and interpreting dreams.

She was known throughout the nation as Voodoo Queen.

Folks came to her from miles and miles around

to show them how to put that voodoo doll

Now to the Voodoo Queen, they all would go

The rich, the educated, the ignorant, and the po’

She snap her fingers, and shake her head

and tell about they lovers, livin’ or dead

Now a ‘ol ‘ol lady named Whita Brown

She askin’ why did her lover stop comin’ around

The voodoo queen gazed at her crystal ball and said

I see him kissing a young girl up in Shakespeare Park

Standing on the corner, kissing in the dark.

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Marie Laveau, the Voodoo Queen,

Way down yonder in New Orleans

Now Marie Laveau,

She held him in her hand, her Voodoo hand

New Orleans was a promise land

All of the folks came from far and near

That wonder woman far to here

They were ‘fraid to be seen right at the gate

So they would creep through the darkness

Just to hear their fate

Holding dark veils ov’r their heads

They were trembling to hear

what Marie had to say

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Hey Marie Laveau (Hey Marie Laveau)

Marie Laveau, the Voodoo Queen,

Way down yonder in New Orleans

Now po’ Whita Brow, she lost h-h-her speech

Tears came rollin’ way down her cheeks

Marie said hush my darling don’t you cry

I’ll make you come back, bidin’ by

Just sprinkle this snake dust all over yo’ floor

And he’ll come back by the morning,

When the rooster crows

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Marie Laveau, that Voodoo Queen,

Way down yonder in New Orleans

Now she made gris-gris, with an old ram horn

Stuck with feathers, and with corn

The big black canal and a catfish fin

Made a man get religion and give up his sins

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Hail Marie Laveau (Hail Marie Laveau)

Marie Laveau, the Voodoo Queen,

Way down yonder in New Orleans

Sad news got to us one morning,

Right about the dawn of day

Oh Marie, I got to tell you she passed away

In the St. Louis cemetery, she lay in her tomb

She was buried last night by the wind of the moon

Oh Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Hail Marie Laveau (Oh Marie Laveau)

Marie Laveau, the Voodoo Queen,

Way down yonder in New Orleans

Way down yonder in New Orleans

”