Our final stop before returning to New Orleans—which felt like home at this point—was visiting the parishes (counties) of Cajun Louisiana, settling for a few days at a hotel in Lafayette while reading Floyd’s Girl and other short stories by Tim Gautreaux.

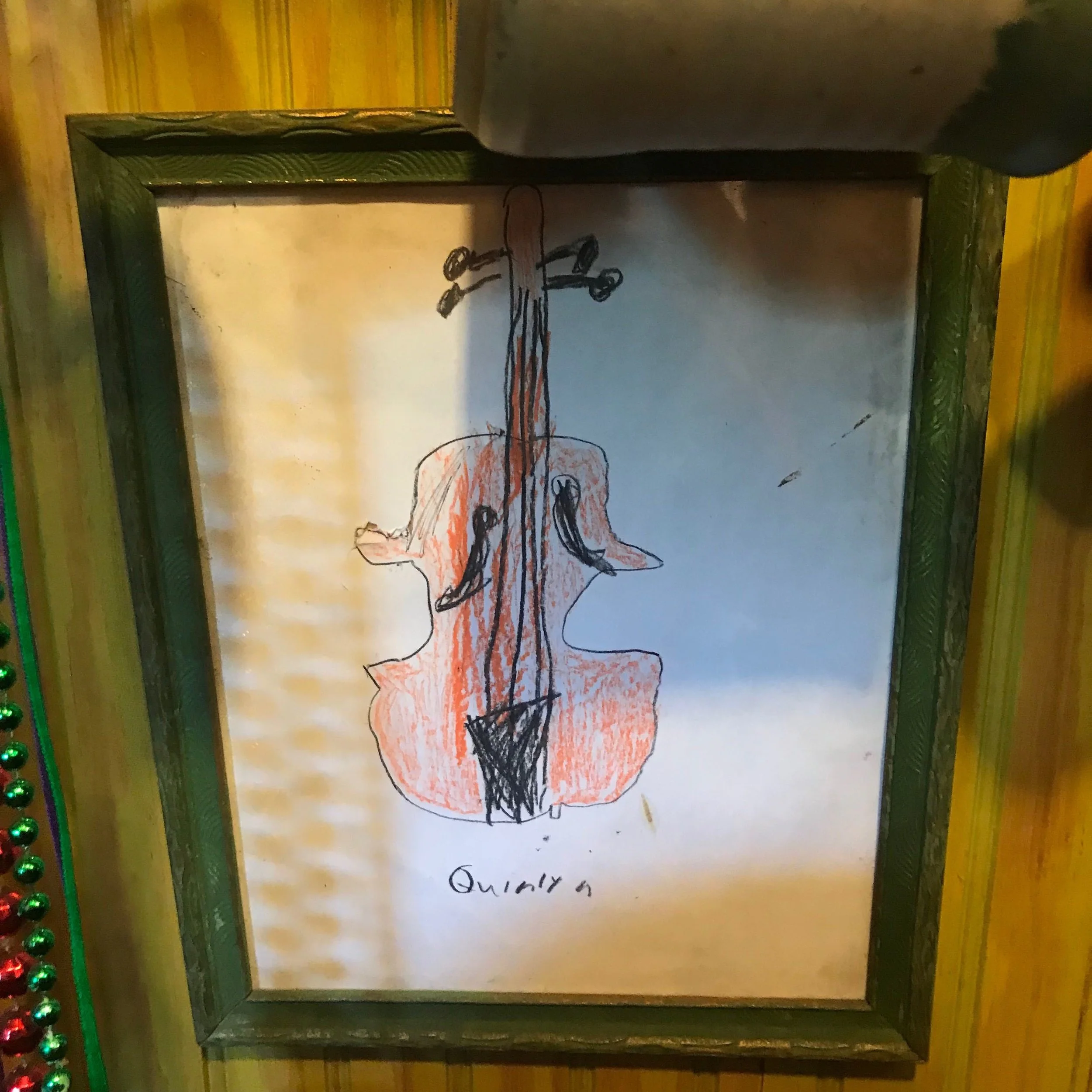

Tim Gautreaux paints a picture of the contemporary Cajun south as a place that is dually violent and Catholic, happy with music and community while peppered with distaste for the “other.” Our few days in the area told a similar story. We munched on traditional Louisiana food at a local café, watching—and even participating in—a jam session of fiddles, accordions, and guitars, immersing ourselves in a Tim Gautreaux world of friendly, curious strangers and the joy of musical collaboration. We learned quickly that it is community rather than quality that makes the music fun to play—but perhaps not so fun to listen to, for string instruments are not so forgiving.

We experienced reminders of a culture that Floyd’s girl was in danger of losing:

“…memories of the ample laps of aunts, daily thunderheads rolling above flat parishes of rice and cane, the musical rattle of French, her prayers, the head-turning squawk of her uncle’s accordion, the scrape and complaint of her father’s fiddle as he serenades the backyard on weekend, vibrations of the soul…”

We experienced these very vibrations of the soul as we participated in an intimate jam session at Tom’s Fiddle and Bow in Arnaudville the next day, which went down as one of my favorite activities on this trip. Never has so quickly a group of strangers made me feel so at home.

------------

Yaya

“Lori, or Yaya as the kids like to call me,” replied the grandmother of ten. She was married to Tom, the owner of the Fiddle shop that our group of thirteen was politely taking over. We had met three of the kids, the oldest a 14-year-old boy, Allister, a lanky boy with kind eyes; 11-year-old Tatum, a little firecracker of a girl, quite smart but mostly terrifying, who had gotten me right on the jugular with a stick twice her size while “dueling” on the back porch; and 10-year-old Sebastian, who if I let him could have spent ten hours asking questions about the bookpacking course and college in general, “so how does this class work? What are credits? How many credits have you done? Do you want to go out to the porch to talk more? Do you want some cake? How does college work?” All of the kids seemed to be quite aware of rather adult topics, each having explained to us that “well, Tom’s not our real grandpa; you see, Yaya used to be married but then she got divorced and then she married Tom, so that’s why we’re here. We’re visiting from Alabama!” I thought it was pretty cute. In response to learning that I was an artsy person studying engineering, Lori told me that she also grew up with both her left and right brains working together—she was a mixed-media artist and an ultrasound operator—and that her dyslexia allowed her to have superior 3D pattern recognition skills that helped her in her job. She shared with us her plans to tear down part of the left wall on the building and add an extension to the store where she could teach art classes. Eyebrows raised, she leaned in and said she was also thinking about building a houseboat on the bayou. She gave us her card, a 1-by-2-inch piece of cardstock with a tiny photo of her printed on one side and her information on the other—she was also a spiritual healer, which was great to know.

Elvis and Priscilla

Rescued by Tom and Yaya, Elvis and Priscilla were a set of jittery but affectionate hairless dogs. Elvis sported an impressive blonde tuft of hair on his head and tail, while Priscilla flaunted a more subdued display of black and grey. Priscilla and I became very close, especially when I was escaping the children, who had frightened me with their sword-fighting.

Gigi

“I’m just being a typical Southerner, talking too much,” Gigi said, leaning forward charismatically in the crowded hallway from which we were all watching a group of men—the oldest an 83-year-old Mandolin player who spoke fluent Cajun French—play Bluegrass in the back of the fiddle restoration store. “Here in the South we say we could talk to a brick wall and have a pretty good conversation!” She laughed at what she said, then thoughtfully continued, “but I don’t feel bad; it’s important to talk to everyone and learn about their lives. I always say that for everyone you talk to, you have to leave knowing at least three things about them.”

She looked at me with wide eyes when I told her I was studying mechanical engineering. She explained how that stuff is completely out of her scope as an artsier person and I said I was like her, that it was a challenge for me every day to study what I was studying. She raised her eyebrows and to my surprise said “wow that’s cool! I’m gonna look for ya in the future, ‘That’s Maria, I know her! I met her at a back-road fiddle shop—” she interrupted her own thought with laughter. I decided I liked her a lot. Before we hugged goodbye, she told me to keep pursuing experiences like this and I said that I would.

We left Cajun Louisiana in high spirits, stepping out of the little shop in a burst of friendly goodbyes. Tom had asked everyone to “say goodbye to our friends from California!” I had never felt more at home than I did at Tom’s cramped fiddle shop, surrounded by people that didn’t hesitate for a second to make me feel like family.

--------------

Our final days in New Orleans were spent savoring our favorite study spots while wrapping up our assignments, saying goodbye-for-now to our favorite streets in the French quarter, and cherishing our last moments together as a rag-tag group of twelve kids following charismatic leader with a talent for accents—combining hotel beds, sharing seafood pasta, bidding farewell to the Mississippi, indulging in the superstitious industries of the city, and buying matching t-shirts that we all agreed to wear at the airport. I am so grateful for this experience, for everything it has helped me learn about myself, for all the amazing people that it allowed me to befriend, and for the opportunity it gave me to produce writing that I am truly proud of. I will cherish these memories forever and am brimming with excitement for what’s to come from the relationships I formed here and the lessons I learned.

So through bittersweet tears I say:

Goodbye for now,

Maria G.C.