Awakening: rousing from sleep, coming into awareness

What is an awakening? As I looked over the first book our bookpacking class would read together on Grand Isle, Louisiana, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, I knew that it wouldn’t be as simple as the surface level definitions the dictionary could give me. I got a surface-level answer from Google, but as our bookpacking class traveled to Grand Isle, Louisiana, I pondered what revelations the next few days on the island would bring to that word.

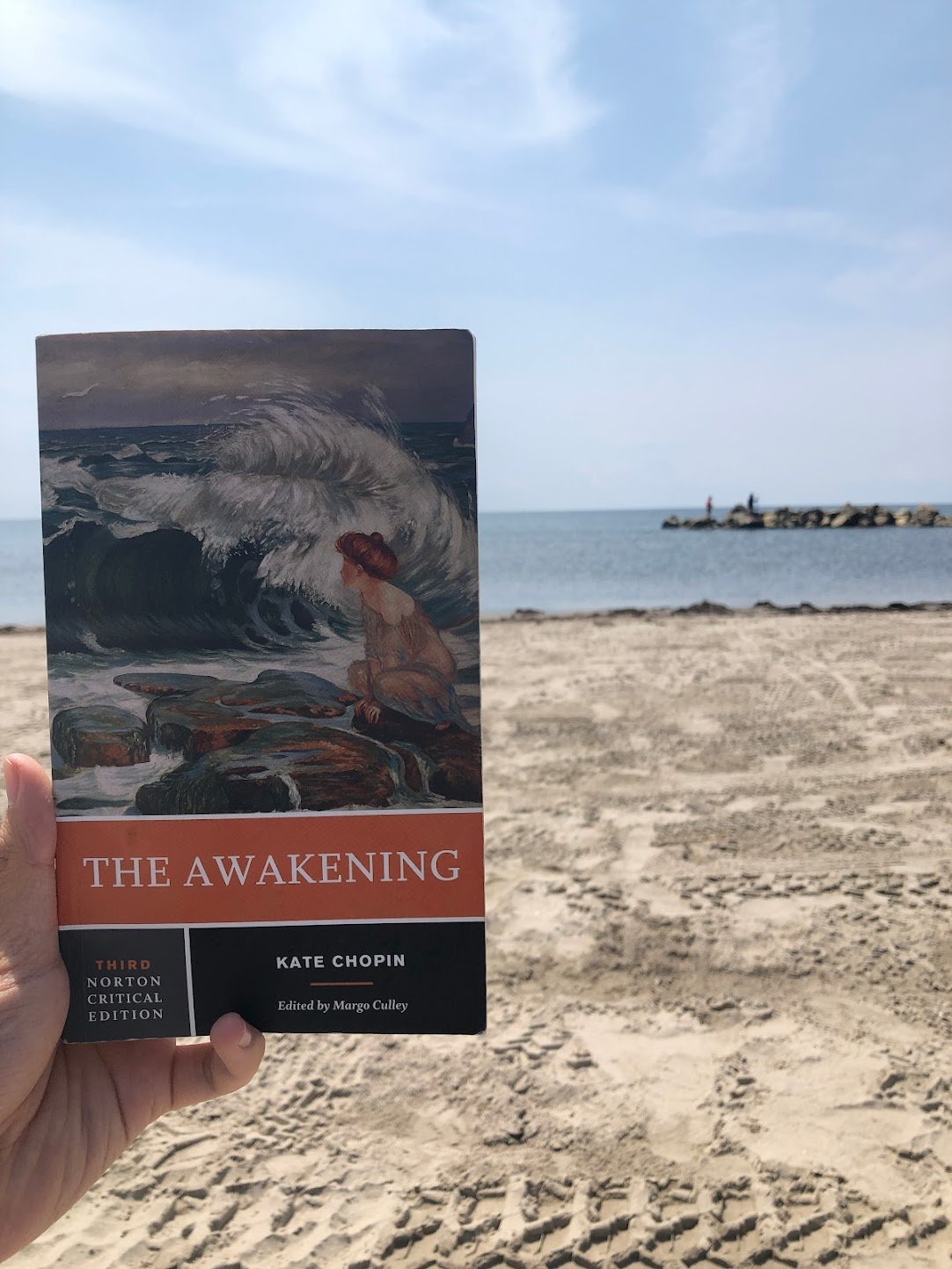

“The Awakening” by Kate Chopin

The island air, warm and heavy, enveloped me the moment I stepped foot onto the shores of Grand Isle. The incessant buzz of the insects, the gentle murmur of the water, and the gentle cry of the shorebirds invited a sense of lethargy that tempts even the most productive of souls into taking a cool, refreshing nap to escape the incessant heat of the midday afternoon. The pace of life felt slower here on the island, almost like I was trapped in time, in another era where the final exams and internship searches that seem to crowd every walking step in my studies as a business student at USC were but a dream.

““How many years have I slept?” she inquired. “The whole island seems changed. A new race of beings must have sprung up, leaving only you and me as past relics.””

It’s in this dream-like location of Grand Isle where our protagonist Edna Pontellier, begins to establish her independence and define her role as a woman and an individual in 19th century Louisiana. The novel sets itself between two worlds, the busyness of the bustling city of New Orleans and the languid romance of Grand Isle. I’d previously read this book for my junior year English class in high school, but this time I felt ready to grasp Chopin’s nuances of exploring themes of repression, femininity, culture, and depression through Edna’s story while experiencing the same warm breeze and froth-tipped waves that she describes so vividly.

“In short, Mrs. Pontellier was not a mother-woman. The mother-women seemed to prevail that summer at Grand Isle...they were women who idolized their children, worshiped their husbands, and esteemed it a holy privilege to efface themselves as individuals and grow wings as ministering angels.”

One way in which Edna feels trapped is in her societal expectation to be this “mother-woman” figure which her friend and her literary foil, Adèle Ratignolle does so well. She fights this societal expectation to have a maternal instinct, declaring that while she’d give her life for her children, she wouldn’t give herself for them. While I’m not bound to the same social expectations that Edna is, within my identity, there are so many facets which bind me to social expectations in my background as a second-generation Asian-American, older brother, son, student and so many more. Although our paths are wildly different, I empathize with her struggle not fitting into the Creole society of the day and her role as a “mother-woman” figure. As a student, I’m constantly struggling with feelings of imposter syndrome, not feeling worthy of my place here at such a prestigious university. Even though logically I know I was chosen to attend this school for a reason, there’s still an emotional tension, a back-and-forth that invites a certain responsibility and necessity to act and perform up to a certain standard in my everyday life to “fit in” with the academic culture and the expectations of myself as an Asian-American student from my peers around me, filling my life with academic and extracurricular activities to be “competitive” for college, then for post-grad life, for the first job, and on and on.

2022 Maymester New Orleans Bookpackers Class Photo

Edna’s awakening from her past subdued self is stemmed from her lover Robert’s awakening of her repressed identity. She comes into awareness of her unhappiness in keeping with societal norms, from her Tuesday’s at home receiving calls to caring for her children and being a good wife to her husband Leonce, and casts it aside to do whatever she wants to do. When questioned by her husband about what possible activity could have led to Edna’s sudden departure from the house on her calling day, she replies simply, “Nothing. I simply felt like going out, and I went out.” This laissez-faire attitude toward her domestic responsibilities and following of her own desires and whims shows her newfound independence and refusal to adhere to social norms.

In many ways, this trip is a personal awakening to the importance of not filling my schedule packed to the brim with things to do as I see others around me compare how busy they are, as if it's a representation of their self worth. At college, I’m used to running about my day, a dozen or so meetings, classes, interviews, and lunches that I’ve got to attend. Here though, when we’ve inquired with our illustrious Lord Chater, also colloquially known as Andrew, what’s on the schedule for the day, he replies simply: “time to rest and read”. I’m used to taking an hour of rest here or there to refocus and recharge. But a twenty-two day excursion that is both somehow class and travel at once is foreign to me. My habitual instincts call out to me to be productive, to get things done and get ahead on work. The waves and the hammock beckon gently though, and I’m entranced by the sweet simplicity of living life laissez les bon temps rouler, or letting the good times roll.

Laissez les bon temps rouler

〰️

Laissez les bon temps rouler 〰️

What does living with the good times mean?

It means I’ll mull over ideas as I wander the lonely streets of Grand Isle with my peers, or as I’m eating my fried catfish po’boy (somehow everything in Louisiana happens to be fried?) at the Starfish Café.

It means reading, toes in the sand that Chopin’s Edna’s children played on, or wading in the warm gulf waters breathing in the same salty air where Edna is first wooed by the voice of the ocean, and later returns at the end of the book, to take her final fateful swim.

It means engaging in conversations around our wooden table about the origins of Creole Louisiana after eating a hearty portion of jambalaya from Joe Bob’s, an affectionately named gas and grill station on the island that is named after the store’s pet cat, or exploring the old tombs in the cemetery that hold the remains of residents of Grand Isle of over two centuries ago.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the other type of awakening to reality when we saw the destruction Hurricane Ida had left on the community of Grand Isle. As we arrived to the location where Andrew had previously brought bookpacking classes to take pictures, he lamented the destruction and loss of what had once been a vibrant thriving community that had been reduced to a broken debris of homes, bridges, buildings, and parks. It was an unpleasant awakening to the destruction this little community had suffered, but its resilience and dedication to rebuild was evident all over the island, as home-made signs and kind-hearted individuals proclaimed their love of the island and their determination to rebuild Grand Isle together.

So what is an awakening? I’m still not quite sure, but I believe it’s a new beginning, a new start to what we’d once been asleep to. It’s a recognition of what’s new and a realization of our surroundings and behaviors that we’d previously been unaware of. I’m looking forward to continuing our bookpacking journey through Louisiana, awakening to a new culture, locale, and pace of life.