I have never visited a place as a “tourist” for this long – almost a month on this trip. Knowing that I will be leaving New Orleans to head back into my ‘normal’ life; that I do not know when, if ever, I will come back to this city, feels uncanny. While I wouldn’t be arrogant enough to say I have become assimilated into the city – returning to the same hotel after our three day stops at Baton Rouge and Lafayette – there was a sense of familiarity to a degree that I had never experienced before.

I deliberately avoided blogging about Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, because I felt emotionally and academically detached from it. To put it bluntly, it did nothing for me. Listening to Andrew and others in the group unpack the book underneath the shade of a tree in Audubon Park; drawing universal messages from it about recognizing the importance of the little shared experiences and relationships, I was affected, but I did not feel like it altered my relationship with the book. Returning to New Orleans, however, I constantly find my mind drifting towards The Moviegoer.

Perhaps it was my attitude at the time of originally reading and discussing the novel. We were immersed in the city – touring, blogging, and writing our papers. It was hard to truly grasp the feeling of “everydayness” when the things I was doing every day were so different – so distant from what I picture as everyday. These last two nights in the city, without any large plans and only one seminar for reflection and self-evaluation, the everydayness finally sunk in.

Binx talks about needing to “learn something about the theater or the people who operate it, to touch base before going inside.” I always found this fact about him rather interesting – he goes to movies to immerse himself in fictional worlds – a very self-aware form of escapism, but a necessary prerequisite to this is being aware of the space itself. We watched Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story at Prytania theaters at canal place. While my memories of the movie are vivid, the movie theater itself has blended into the other movie theaters in malls that I have been to. So much of what I remember is the experience of watching a movie, the experience provided to me by the screen, but the space itself escapes me.

Thinking back on these past few weeks; perhaps, my eyes were too drawn to the metaphoric screen, and not the space itself. Of course, I was detached as I am just watching a movie, but, in a sense, the difference between Binx and I when we visited a movie theater captures the shift in attitude I had. Experiencing a new place through the filter of its literature is something I have never done before. For most of the books, this enhanced my engagement and immersion in their stories, but for The Moviegoer, paradoxically, the filter of literature blocked my ability to emotionally connect with Binx’s solution to his existential angst at the end of the novel. In a way, this is not too different from Binx needing to see past the layer of movies that tint his perspective.

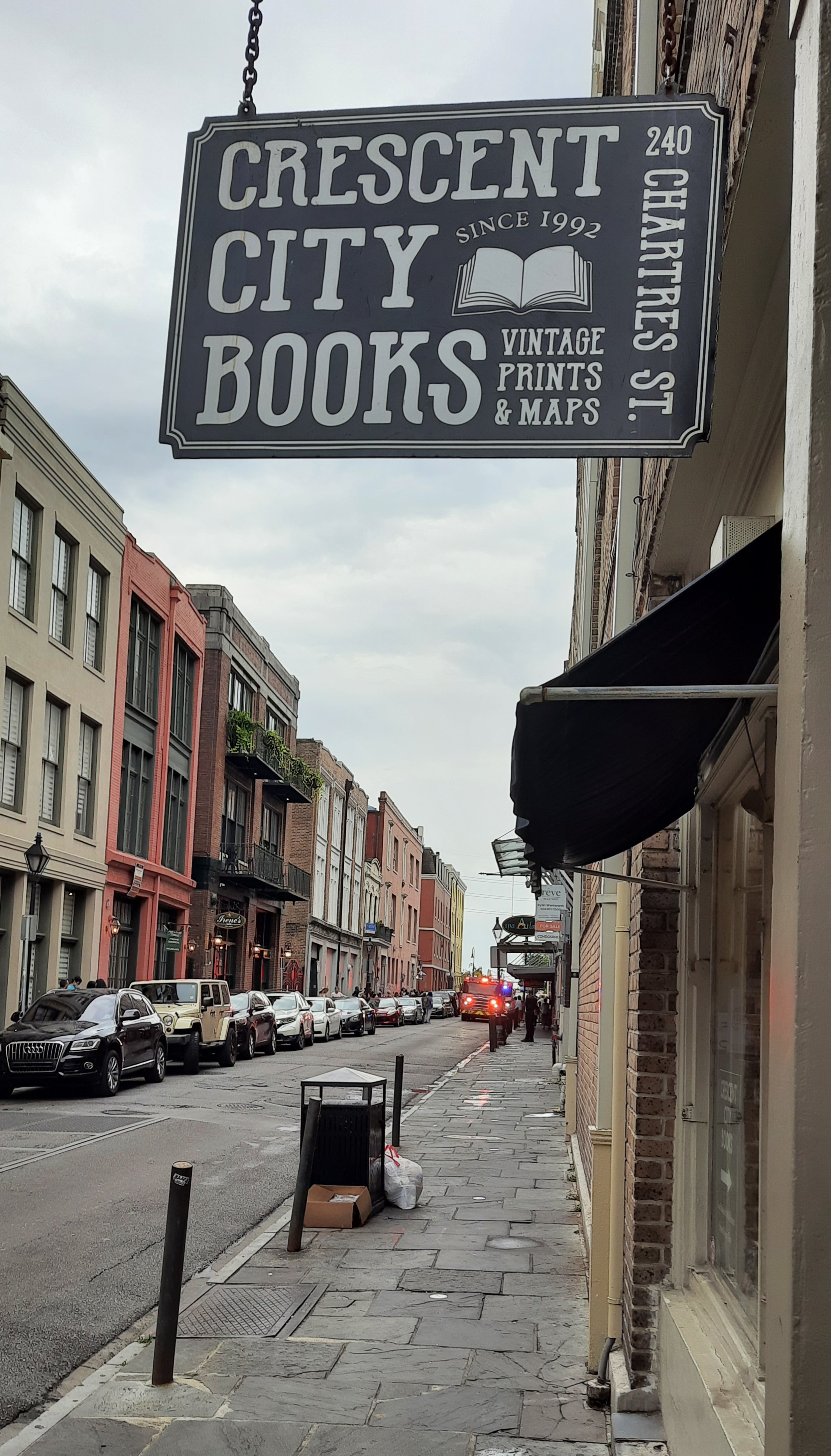

Initially, after we returned, I was still partly experiencing the city as a moviegoer. Early on, when I visited Arcadian Books and Prints, the owner gave me a map of all the independent used-bookstores in the French Quarter. I visited every one of them except Dauphine Street Books, and the first thing I wanted to do when we were back was visit it to complete that map, which I did do.

But after this, even though there was a lot of the city I wanted to revisit, new places, museums that I wanted to explore, the everydayness set in. Maybe my mind was preparing itself for what followed the end of this trip. Regardless, reaching the end has finally given The Moviegoer a more definite place in the version of New Orleans that is in my head. I still do not completely connect with it at this stage – the ending feels far too resolved – but I do not feel as detached from the book.