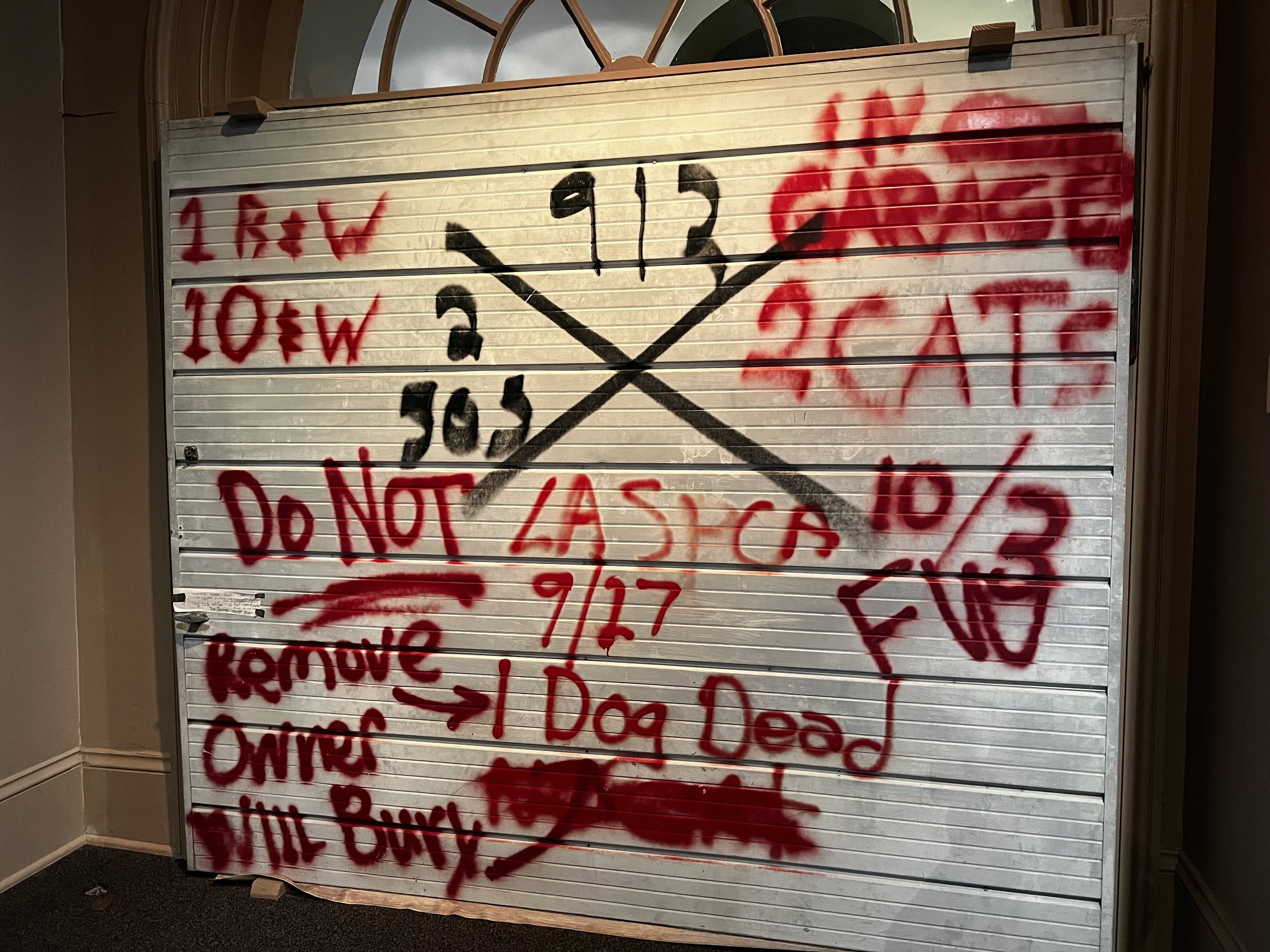

A spray-painted number is the only remnant of what used to be The Yellow House.

To most people who somehow manage to stumble upon Wilson Ave, “4121” is just a meaningless, random number on a curb. In fact, these people will probably pass by without even noticing that it’s there at all. To me, seeing the number before my very own eyes is like going on the Universal Hollywood Studio Tour and physically being at the filming sets of movies I’ve only watched on screen. It felt unreal. But, to Sarah M. Bloom, the spray-painted “4121” is the crumb that contains all the memories of Ivory Mae’s “unruly child” that she was very much ashamed of.

Out of the three perceptions of “4121,” Sarah’s is the one that hits closest to home, even more than my own. The house being an embarrassment to her reminds me of my mom. See, as cool as my mom is with having guests over at our house, she always greets the idea with, “You better clean the house before they come. Aren’t you embarrassed?” Maybe it’s the effect of my grandma’s upbringing on her, maybe it’s the pure Asian blood rushing in her veins, or maybe it’s just an excuse to get me to clean the house for her—whichever the reason may be, a part of my mom is seemingly ashamed of the state of shambles that characterizes our house.

In Indonesian, we have the phrase “kapal pecah,” which literally translates to “a broken boat.” This is my grandma’s go-to phrase when describing the state of her children’s houses because no matter how squeaky clean the houses look in our eyes, it will never be up to her ‘Asian grandma’ standards. But… hear me out. I swear our house isn’t that bad. Sure, there may be mails sitting out on random surfaces around the house, or cups, or our dogs’ toys… But, you know, we also try our best to clean them out every couple of days when we’re all not too exhausted from our jobs and schoolwork. So, really, it’s not that bad. And, frankly, I think my mom knows this too. Despite the slight shame she may have, a bigger part of her always cherishes that house because there are more valuable aspects than the (infrequent) messes around the house—all the memories it carries, what she had to go through to purchase it, and the most important of all, her gratitude towards it. That last part? That’s the advice she always gives me whenever I’m going through a difficult time. “Always be grateful for everything that comes your way.” So I guess that’s how she views our house too, because having a roof to sleep under each night is, in itself, something to always be grateful for.

“This is the place to which I belong, but much of what is great and praised about the city comes at the expense of its native black people, who are, more often than not, underemployed, underpaid, sometimes suffocated by the mythology that hides the city’s dysfunction and hopelessness. If the city were concentric circles, the farther out from the French Quarter you went—from the original city, it could be reasoned—the less tended you would be. Those of us living in New Orleans East often felt we were on the outer ring.”

Personally, I think this sense of gratitude didn’t struck Sarah herself until the Yellow House was gone. While I do think she could’ve given the house more credit, I also must admit that her deep feeling of shame towards it was very much justified. I mean, the Yellow House itself was the epitome of the New Orleans nightmares that were always quickly coated by the city’s Big Easy image. Granted, the house had walls that were peeling, wirings that were exposed, sink that was collapsing, and rats that were roaming around in every corner. Besides these, though, the main issue was that the Yellow House was never built on a solid foundation. Rather, it was built on a swamp and grounds that were way too soft for its own good. From today’s perspective, we can easily ask, “what happened to mandatory house inspections?” From their perspective, the answer was simple: negligence. It was the negligence of the neighborhood, the city, and the government that was to blame for the fall of New Orleans East. Even pre-Katrina, the authority never cared enough to put into place infrastructures that would be safe for living, let alone to build neighborhoods that would allow its people to thrive. Not to the locals’ surprise, during and post-Katrina was exceedingly worse.

It's true. The locals weren’t too surprised with the whole Katrina disaster. Unfortunately, for outsiders like me, we might’ve been more ignorant to the truths that overshadowed this catastrophe, so the whole thing was quite shocking. For me at least, it wasn’t until I visited the Hurricane Katrina exhibition at The Presbytére that I learned of the truth. Throughout my visit, as I went around reading and watching eyewitness accounts, I couldn’t help but shake my head, make “tsk tsk” sounds, and furrow my eyebrows at the absurdity of it all. So, what is the real truth behind Hurricane Katrina? Hell on Earth—dead bodies floating on the flooded streets, people screaming for help, and those who were “evacuated” being transferred into locations which had even fewer resources. Yet although these truths existed, they were otherwise told by the media. Much like how the locals were not made aware of the situations at the time, outsiders were also told lies by media coverage of complete and successful evacuations throughout. We weren’t told that hospitals were falling apart and more people were dying; we weren’t told that the entire state was undergoing shortages of food, water, and supplies; we weren’t told that all locations of refuge were losing power and electricity, thus causing a deadly increase in temperatures.

“Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house.”

As for New Orleans East, all that remained following Hurricane Katrina was the “physical wasteland” it had then become. Lacking its physical structures, the Yellow House and its memories now exist only within Ivory Mae and her children. So while this mass of land has come to represent the loss and suffering of its people, it might have also been Sarah’s freedom from the house she detested.

After all, the physical structures which she felt a deep sense of shame toward had all fallen apart then, and “the story of [the Yellow House] was the only thing left.”