Napoleon Buonaparte remains one of the most divisive figures in French history. He was an emperor with too much power, but he did great things with it. He supported the arts, reorganized the banking and educational systems, was an excellent general, and codified the laws. He was a tyrant, but France may have taken decades without him to achieve this crucial foundation of laws and reforms. I have studied Napoleon in the past, but I only retained the memorable sections. I recalled him being shipped off to an island as punishment. I also remember him fighting in Russia, only to lose because it got too cold. These don’t create the most positive or heroic portrait of Napoleon. Based on what I had learned in high school, I remembered him as slightly pathetic, but his grasp on many French citizens is strong. His tomb was gigantic and centrally placed in the gorgeous Les Invalides. The statues made him appear like a strong leader of the people, and some flowers were even left at his foot by visitors. However, even this building was controversial as many did not want to celebrate him.

In Les Misérables, Marius grows up hating both Napoleon and his father because of how his grandfather and the salon speak of them. He was indoctrinated by these influences, and this turned him into a fierce royalist. Marius’ impression of his father and Napoleon lasts years until he learns the truth about how much his father loved him. This new information launches him on a new trajectory intellectually. He is forced to start from scratch and relearn everything about the world. His grandfather had kept him isolated, which stunted his emotional development. When he finally broke his shell and formed his own opinion, he joined the revolutionary group the Friends of the ABC. Marius’ morals and politics greatly change as he loses the conditioning he grew up with. He reevaluates his impression of his father and, as a result, his impression of Napoleon. Marius is forced to confront his learned prejudices against Napoleon and begins to see his glory. We would like to believe we are in control of our thoughts and opinions, but so many of our beliefs are shaped by other influences that can be difficult to shake.

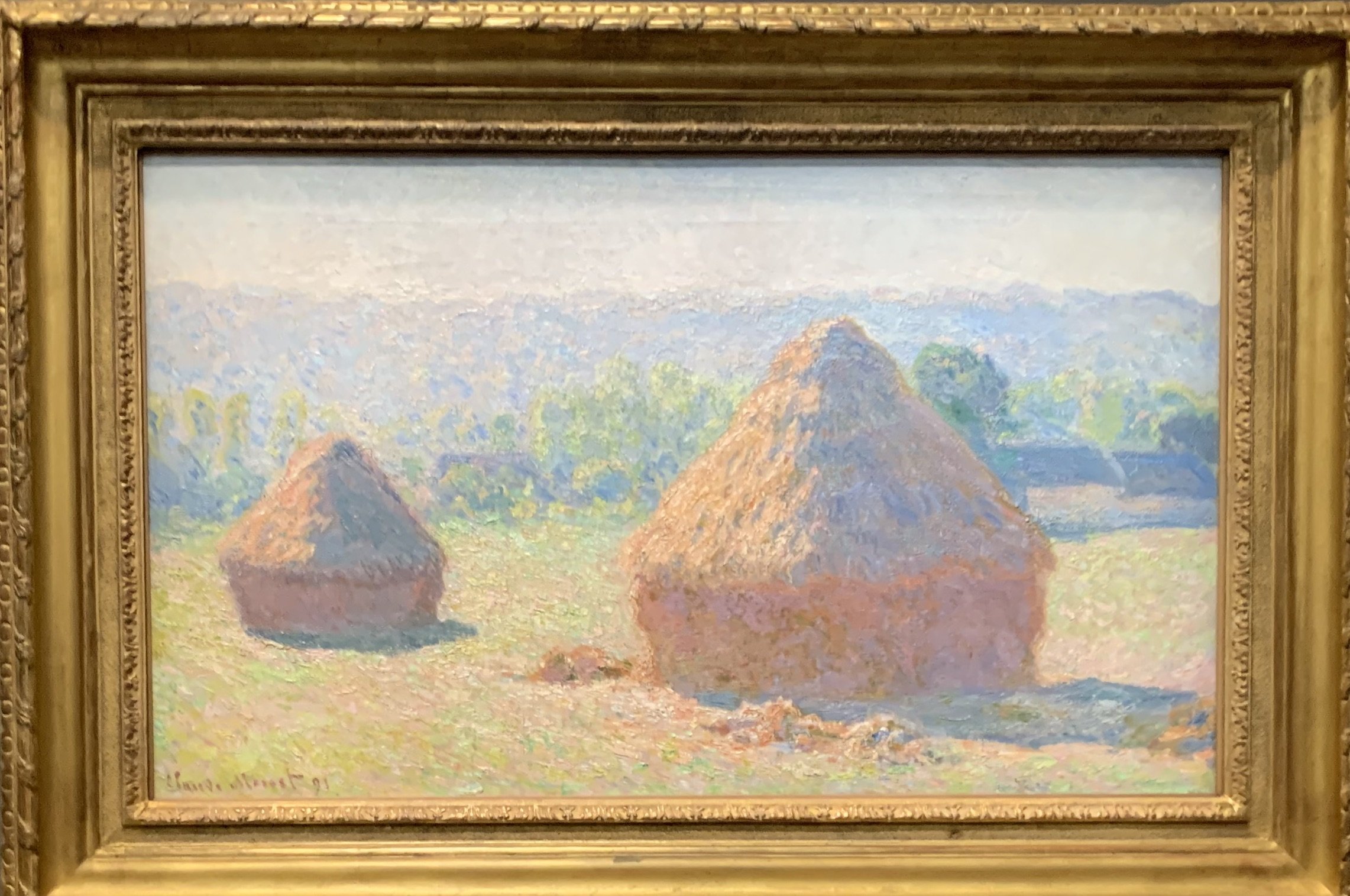

On Monday, we went bookpacking Napoleon - wrestling with his legacy as Marius does in the novel. The way we remember prolific figures like Napoleon says a great deal about the nature of history. The victorious people are the ones who get to write history. However, the collective memory of groups can also be poignant and play a strong role in how we remember historical figures. Our memory can be manipulated, as we have seen with propaganda. Sometimes the way we remember someone or something is more powerful than just knowing specific facts. Political campaigns use propaganda all the time to get voters to have a negative impression of a candidate. This emotional response is harder to unlearn than knowing a candidate’s stance on issues. Art plays a large role in this. Every painting is a result of particular artistic decisions made by an artist. The way they choose to represent a person/place is never accidental. An artist can choose to glorify something or condemn it, and the result shows in the art. It is commonplace for monarchs to hire painters to create portraits designed to exalt themselves and their court. The Coronation of Napoleon, painted by Jacques-Louis David, screams propaganda to me. The neoclassical piece hung at Versailles is a towering canvas that features Napoleon and his wife in glittering clothes in front of an adoring audience. Anyone seeing this painting can feel the power and prestige of Napoleon’s regime. Even when he has long died, the painting remains to influence viewers in a certain way. Propaganda is effective because it subtly influences you to think about someone a certain way, which lasts much longer in your memory than just facts.

Marie Antoinette is another prime example. She has been used as a figurehead for everything wrong with the nobility. We explored the Conciergerie over a week ago, which was where Marie Antoinette was held before her beheading in 1793. Her cell has since been turned into an oratory dedicated to her memory. People know Marie as promiscuous, pompous, and devoid of any sympathy for the poor struggling while she enjoyed life as queen of France. According to the information in the Conciergerie, people even spread rumors she had an incestuous affair with her son (which was completely untrue). Marie was actually quite charitable, witty, and devoted to her children. So why do we all remember her so poorly? Revolutionaries needed someone to unite people for their cause. Marie Antoinette served as an easy scapegoat to pin all the ails of the monarchy on. Revolutionaries even created rumors that she said “let them eat cake” to further her scandalous reputation. She was a victim of circumstance and propaganda, which led to her execution. The fact that people still remember her poorly speaks to how easily our memories can be manipulated and taken advantage of.

Our decisions are much less rational than we would like to believe. They are affected by influences that are difficult to see, like the people around us and our own biased views. The only way to counteract this is to try to make the information we receive as objective as possible. Propaganda is easy to come by, and it is far more subtle today than it was during the 19th century. In the age of the internet, people are encouraged to create the most eye-catching headlines and posts to maximize engagement. To create our own opinions and impressions, we must stay aware. Objective information is not just handed to us anymore, we must hunt for it. Discerning fact from fiction is more difficult than ever, but it’s something that must be done if we hope to truly understand and make decisions for ourselves and our society.