When I told my friends about my summer plans, they couldn't help but express their happiness and jealousy over the fact that I was traveling to New Orleans, one of the most hype cities for young people in America. They told me about the legendary Bourbon Street, Mardi Gras, and the festive spirit of the city. So I held high expectations for the Maymester course and knew the city would offer good cuisine, leisure activities, and exposure to Creole/Cajun culture. You could only imagine my anticipation to finally see the city.

The first thing that struck me about the city of New Orleans was the interplay between the past and the present. In contrast to many cities in California, New Orleans contains a vast history that stretches back to the arrival of the French and Spanish in the New World. The beautiful authentic European architecture definitely popped out at me. In fact, entire sections of the city look completely slathered with pastel colors and have street artists and performers at almost every major cross street. The city itself is thoroughly spread out, walkable, open, welcomes tourists, and is a melting pot for diverse peoples in the South. I can understand why half a century ago Tennessee Williams said, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” In some ways, the city of New Orleans resembles my home city of San Francisco in that it offers a wider degree of individualism, liberalism, diversity, licentiousness, artistic expression, and civic responsibility that are not widely available in other American mid-sized cities.

Beneath the grandeur of the city, New Orleans contains a rich and dark history steeped in slavery and French colonialism. Although many people make the argument that New Orleans today blends different socio-economic and racial groups together, New Orleans was formerly known for its heavy involvement in the Atlantic slave trade to the extent that the Southern region of Louisiana was coined the "Gold Coast." The buying and selling of African peoples peaked in 1807 when the international slave trade was banned in the United States. Subsequently, the movement of slaves from the North to the South accelerated due to what historians deem today, "the Second Middle Passage." As a result, the institution of slavery became the main economic engine driving the economy within the South whereas the North began to industrialize its workforce and modes of production instead.

Our trip to the Whitney Plantation exposed the dark and brutal history of slavery and its impact on Louisiana's social, political, and economic development. After our morning seminar, we took individual portraits and then waited for an hour in the plantation's expensive bookstore that sold fashionable African-American literature, books, cds, African clothes, and trinkets. Our wonderful tour guide Ali took us outside and immediately, we went to the church adjacent to the bookstore. I couldn't help but admire Ali for his eloquence and sophistication. Ali ensured that every single person in the group understood the full weight of slavery on the African body, the universality of slavery throughout human history, and the function of slavery in the Southern economy.

With his booming charismatic voice and impromptu style, Ali delivered a powerful presentation on the architecture of slavery and the importance of educating youth especially black youth on their history today. He delineated the brutal and psychological mechanisms put in place to control slaves and the profit motive influencing the Southern genteel class to maintain slavery. Ali also discussed how slavery in the United States was different from any other type of slavery in human history in that for the first time in history, race and religion were used to justify the perpetual enslavement of another group of people. The details concerning the first colonial attempts to enslave Native Americans and Pope Nicholas V's "Dum Diversas" sanction in 1452 that authorized the enslavement of pagan peoples were also very gripping and highlight the complex interplay between major European institutions (the church, the marketplace, European shipping industries, the aristocrasy) in the conception of this new form of slavery in the United States.

The Black Baptist Church

The plantation originally didn't possess a church. The church was eventually acquired from demolished pieces of a black Baptist church miles away from the plantation. During slavery, slaves could enter the church, but were not allowed to preach, read the Bible, and were only told specific scriptures regarding humility, obedience, and the rewards of Heaven in sermons that justified slavery. If a slave was caught reading, they were given 10-20 lashes as punishment. To paraphrase Ali's words, "It was deadlier for a slave to learn how to read and write, than it was for a slave to attempt to run a way." Soonafter, the church was restored and descendents of black slaves today assume ownership of the church.

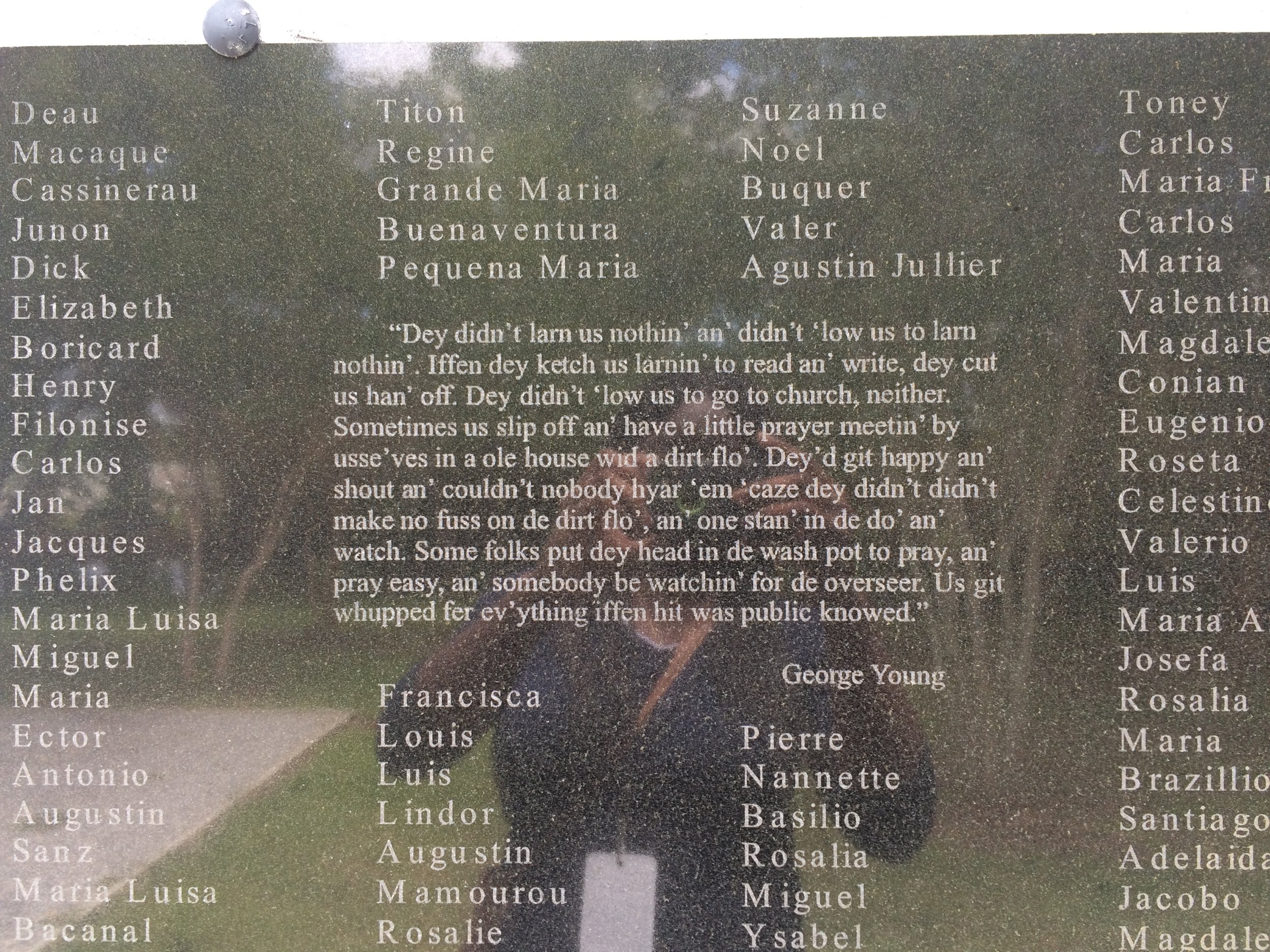

Wall of Honor

The Wall of Memory commemorates the names of 350+ slaves who lived, labored, and died on the plantation. Academics from neighboring universities such as the University of New Orleans and LSU received grants to document the names of slaves that were found in the papers discovered in the Big House roughly twenty years ago. The average life expectancy of African slaves was twenty years and the death toll totaled -12 percent or 112 out of 100 people. Slaves were also sexually exploited to breed mixed race children. Since these children were the property of their slave masters, slave masters usually gave their children French names.

The Field of Angels

The Field of Angels is a memorial dedicated to the 2,200 slave infants who were born in the St. John the Baptist parish between 1823 and 1863. Since infant mortality rates and diseases in motherhood were exceedingly high, most children died before their second birthday. Most children did not receive a proper Catholic burial and were often buried in large earthen holes on the plantation.

The Slave Quarters

There existed roughly twenty houses on the plantation and were carved out of cypress trees. Slaves prepared meals, gardened their vegetables, weaved cloth, and slept here. On average, slaves worked roughly 12-18 hours a day and utilized deadly tools to cut down sugarcane and tobacco plants. In accordance to the French noir codes, children began work in the fields at the age of 10 and elder slaves stripped the leaves of indigo plants because they were poisonous and in old age. High-skilled slaves such as carpenters and blacksmiths often were the first to buy their freedom and purchase their slave family's freedom.

The Big House

Ambroise Heidel was the founding father of the plantation. In 1721, he emigrated to the United States with his family. He started out as a modest farmer and then bought the original land tract of the plantation in 1752. He became a wealthy land owner of indigo, tobacco, and sugarcane. Eventually Heidel passed the property off to his son Jean Haydel Sr. who expanded the farm and acquired more acres of land in 1803. Soonafter, Haydel Sr. bequeathed the property to his son Marcellin. After his death, his widow Marie Azelie Haydel bought the plantation and produced more sugarcane, an astounding 407,000 pounds of sugar during one grind season due to advanced technology in agriculture.