I’m back in Los Angeles now, and as I reflect on my time in Louisiana, I ask: how am I different than I was at the start of the trip?

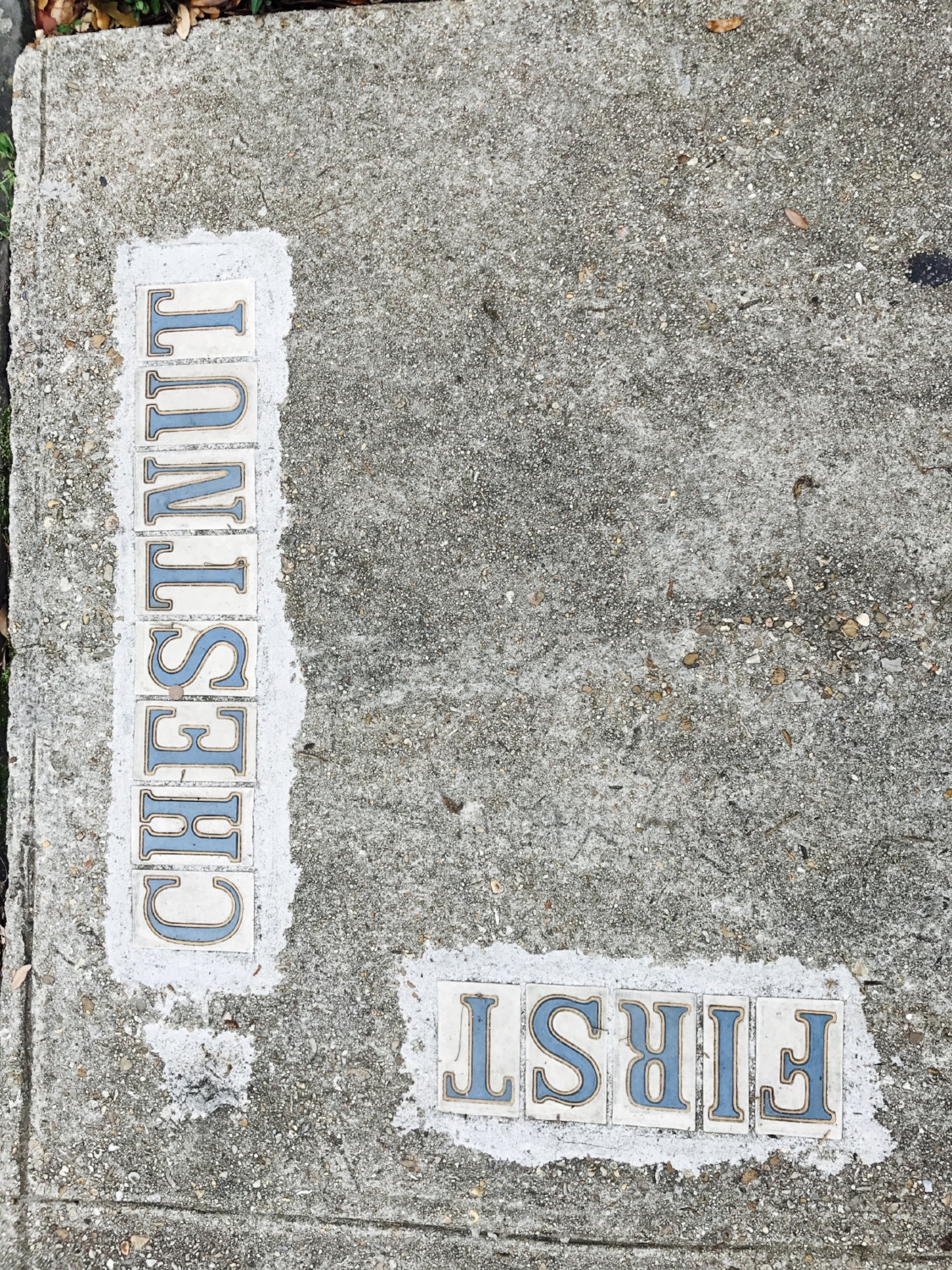

There are simple answers to this question. I am 21 now (woo!); my face feels a lot cleaner (something about the humidity opening up pores? I’m not entirely sure how that happened); I know what creole/cajun food tastes like; I have experienced the glory of a Cafe Du Monde beignet; I now know the streets of the French Quarter better than my hometown’s; I can read a whole lot faster than the beginning of this trip; and my heart is definitely a few years closer to a heart attack (note to self: daily fried food is a no-go). In a few years, I may look back on my time in New Orleans and remember these things, but I do not think these memories are necessarily “life changing.” Yes, eating a beignet was wonderful! Its pillowy center, encapsulated by a crispy deep-fried crust, topped with a mountain of powdered sugar, was quite an incredible flavor impression, but will it affect the way I see the world? Definitely not.

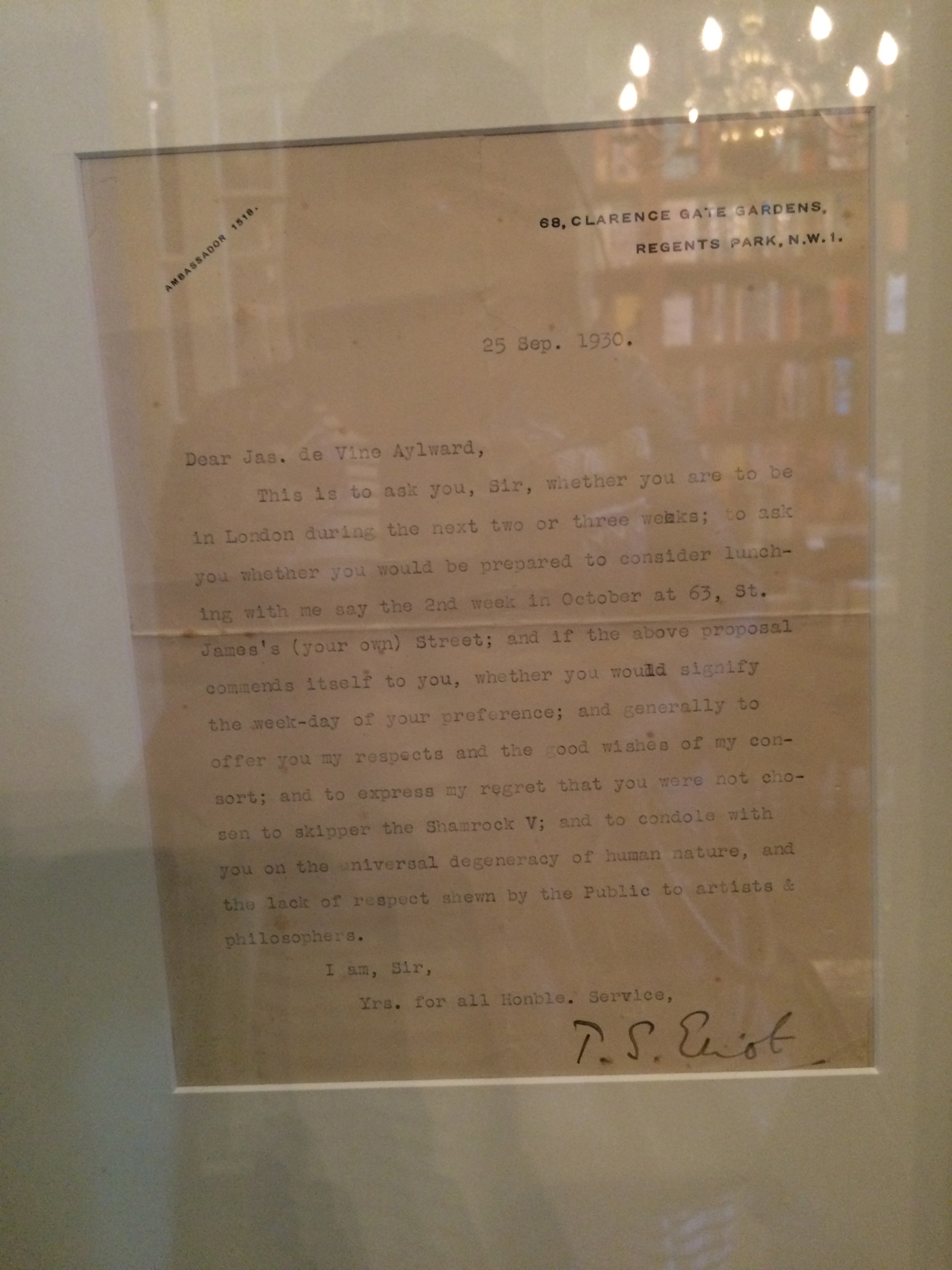

Andrew sent our group this quote at the beginning of the trip regarding travel:

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”

I love food, so when I travel, I look for the best food that the place has to offer. From the fanciest of restaurants to the ghettoist of street shacks, I want to try everything. I am especially interested in region-specific, cultural foods that will be hard to find in LA. The search for food has led me to uncomfortable places and types of food I would rather not have again, but the marvelous palate explosions of a hit far outweigh the few memories of repulsion. This process of immersive discovery applies to much more than food, and I think this is what Mark Twain is talking about in his quote.

Google translates travel as:

making a journey, typically of some length or abroad.

It would be dangerous and foolish to assume that this “travel,” on its own, will combat species-old powers such as “prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” Twain must be under the impression that travel is more than arriving at a new location and moving your body through that place just to say you’ve been there, for one could travel through the heart of Los Angeles, down Figueroa St., and be oblivious to the wonderful Korean, Mexican, Chinese, and all other wonderful types of cuisine that LA has to offer.

It has become much easier to miss things. You can travel to a new place and find stuff that makes you feel at home, and it’s easier to gravitate towards things that you are familiar with. I admit to this; whenever I go to a new place, I usually have to find some sort of rice dish because rice reminds me of home (Maybe that’s why I gravitated so closely to rice and beans, a.k.a my favorite creole dish). Twain isn’t talking about going to a place and finding a nook that reminds you of the “little corner” you left behind. Instead, he glorifies travel because it is the very opportunity to escape that tendency and discover a world that is literally out of your own.

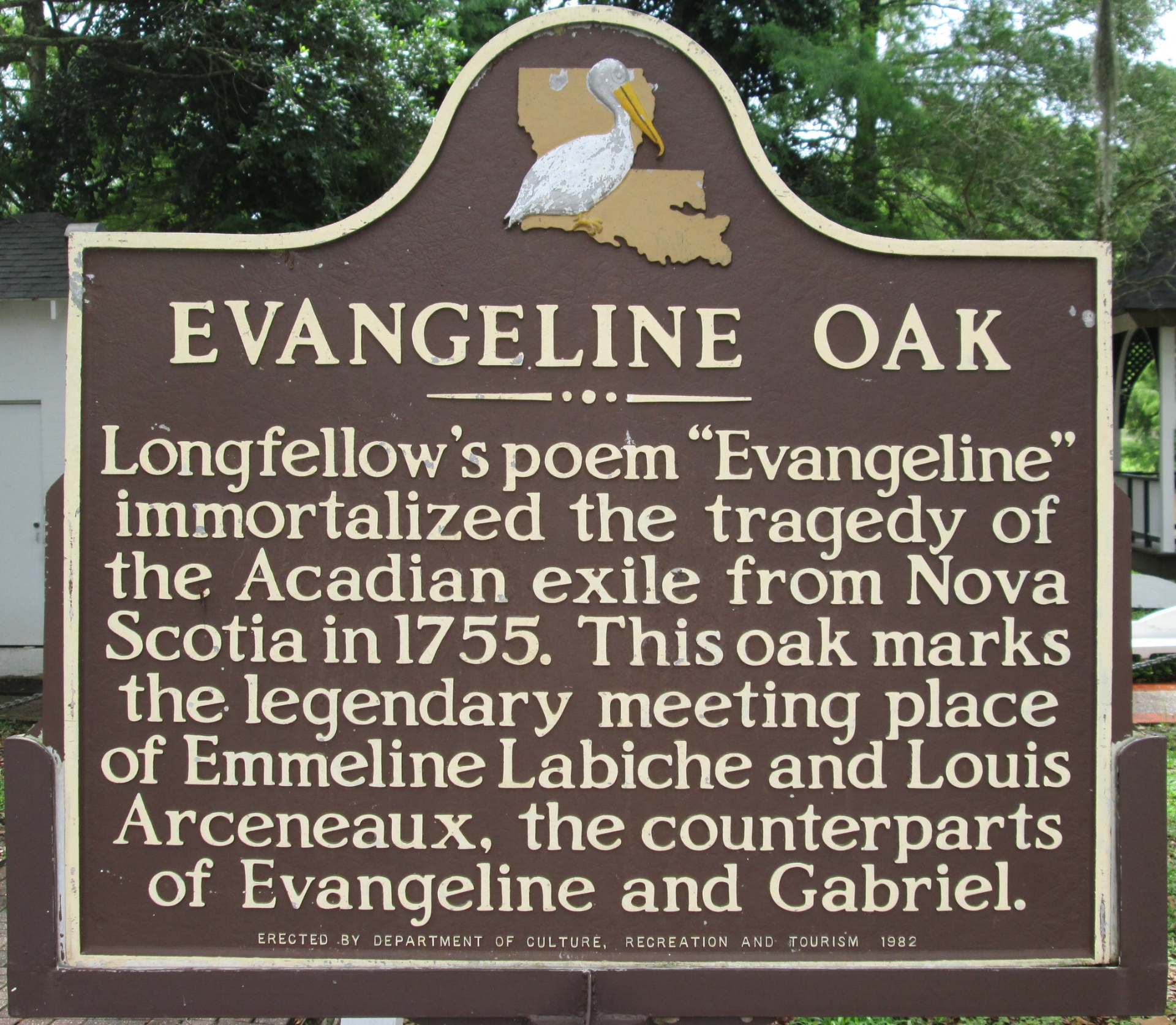

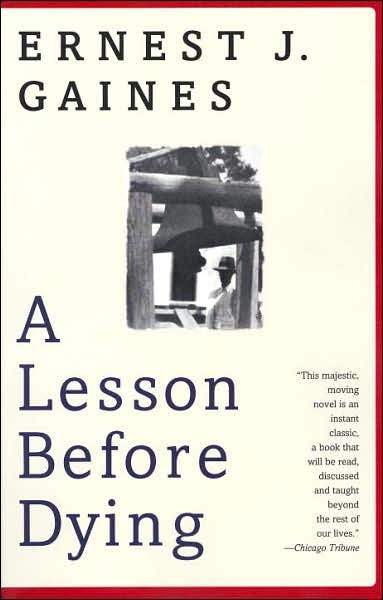

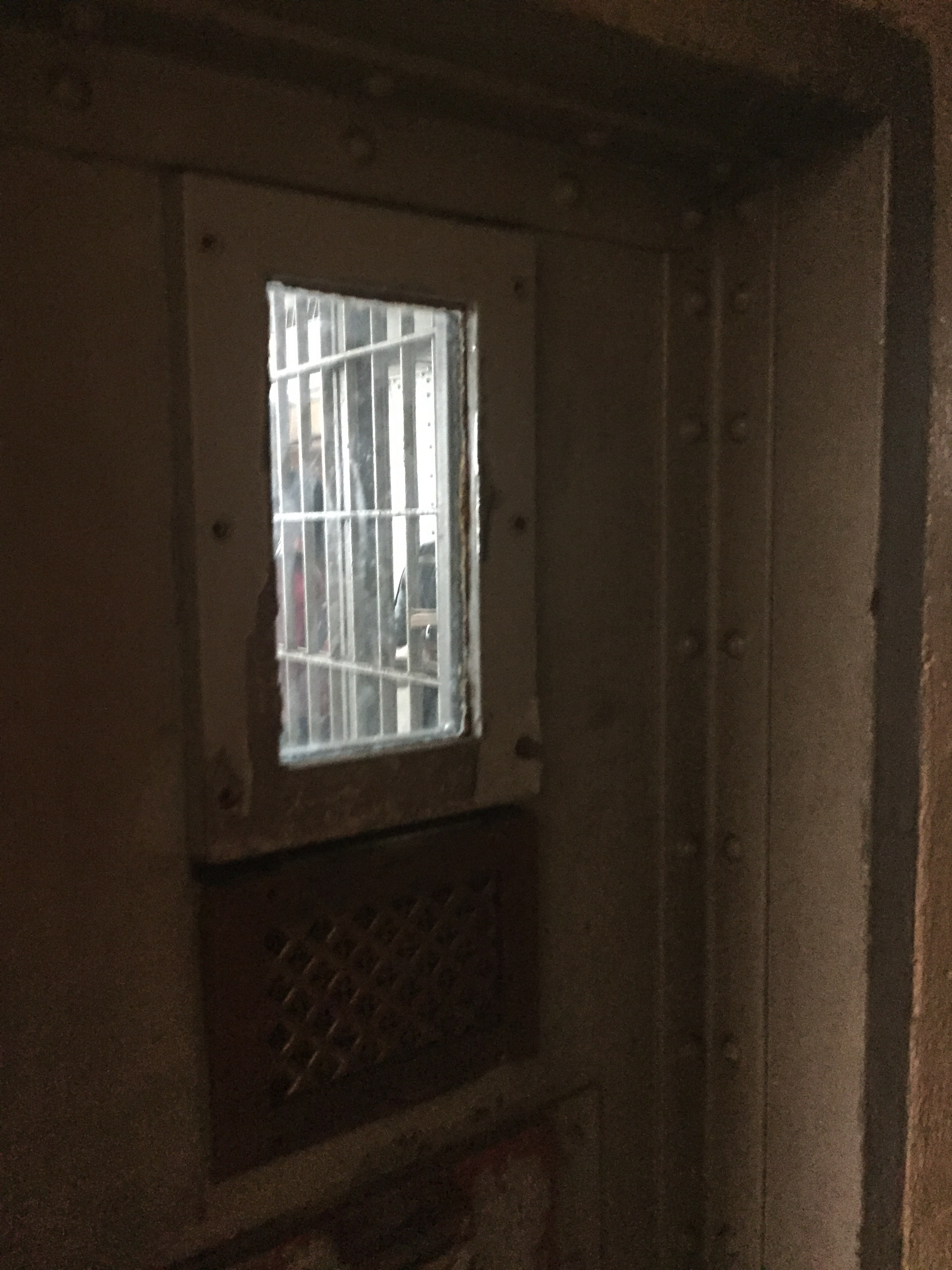

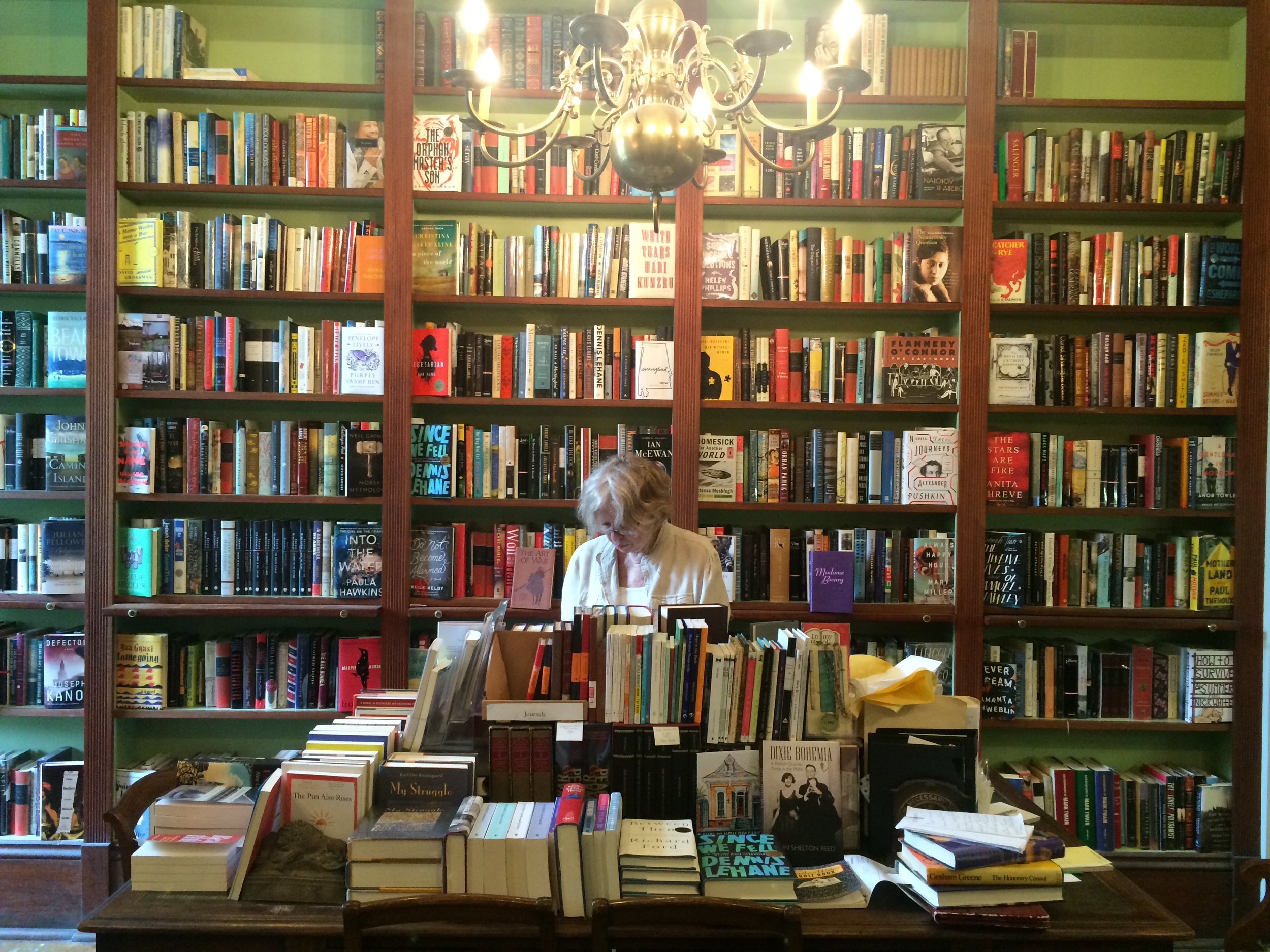

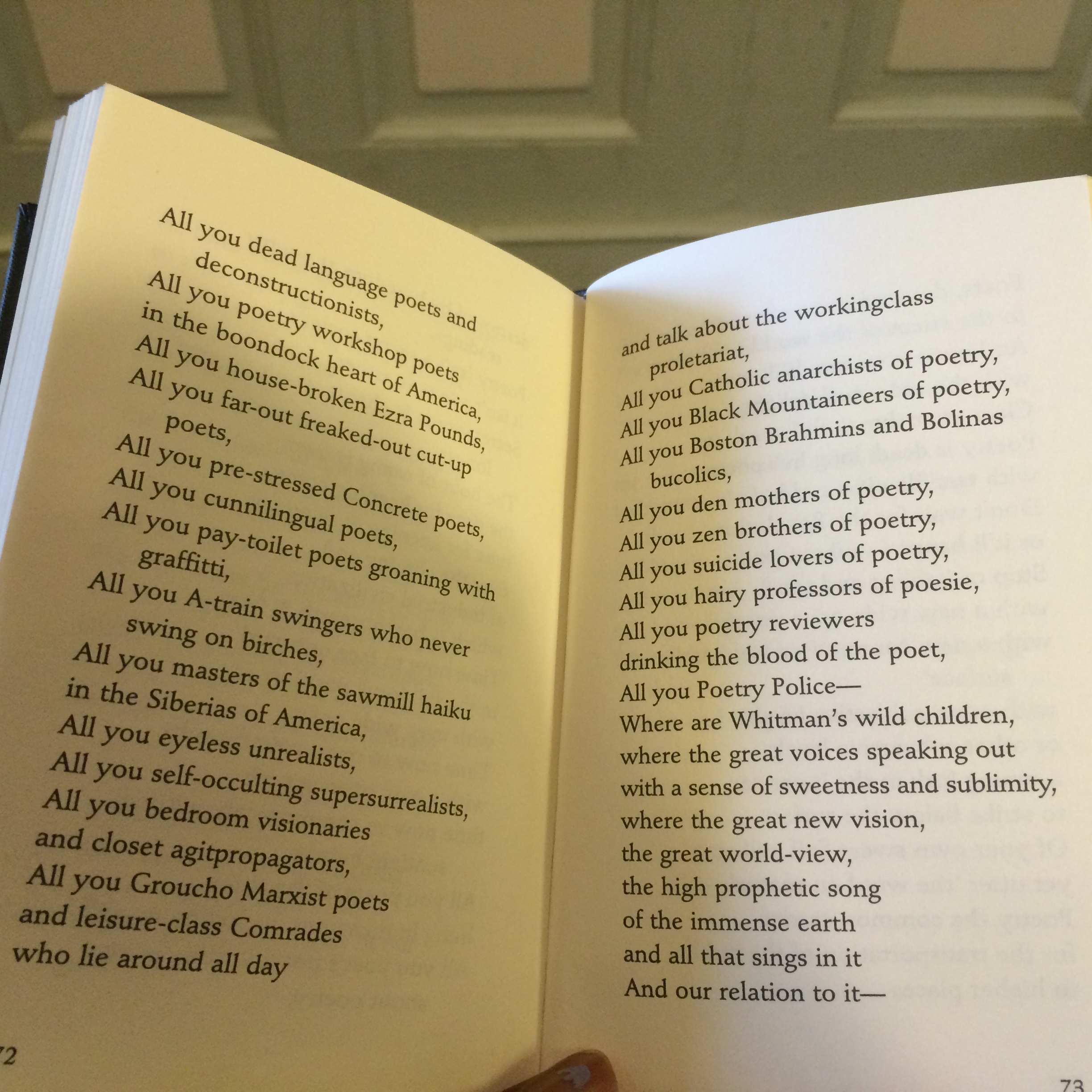

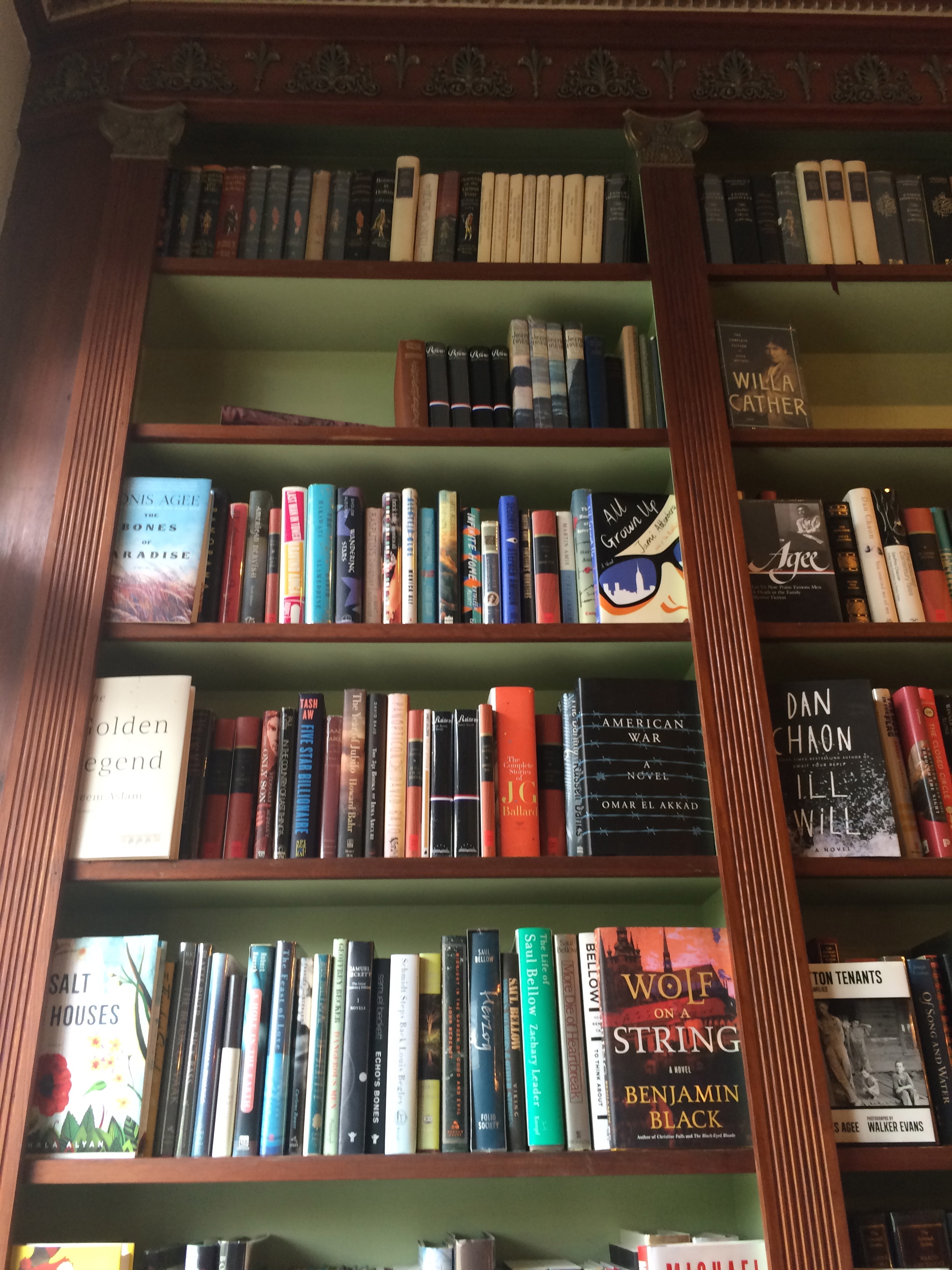

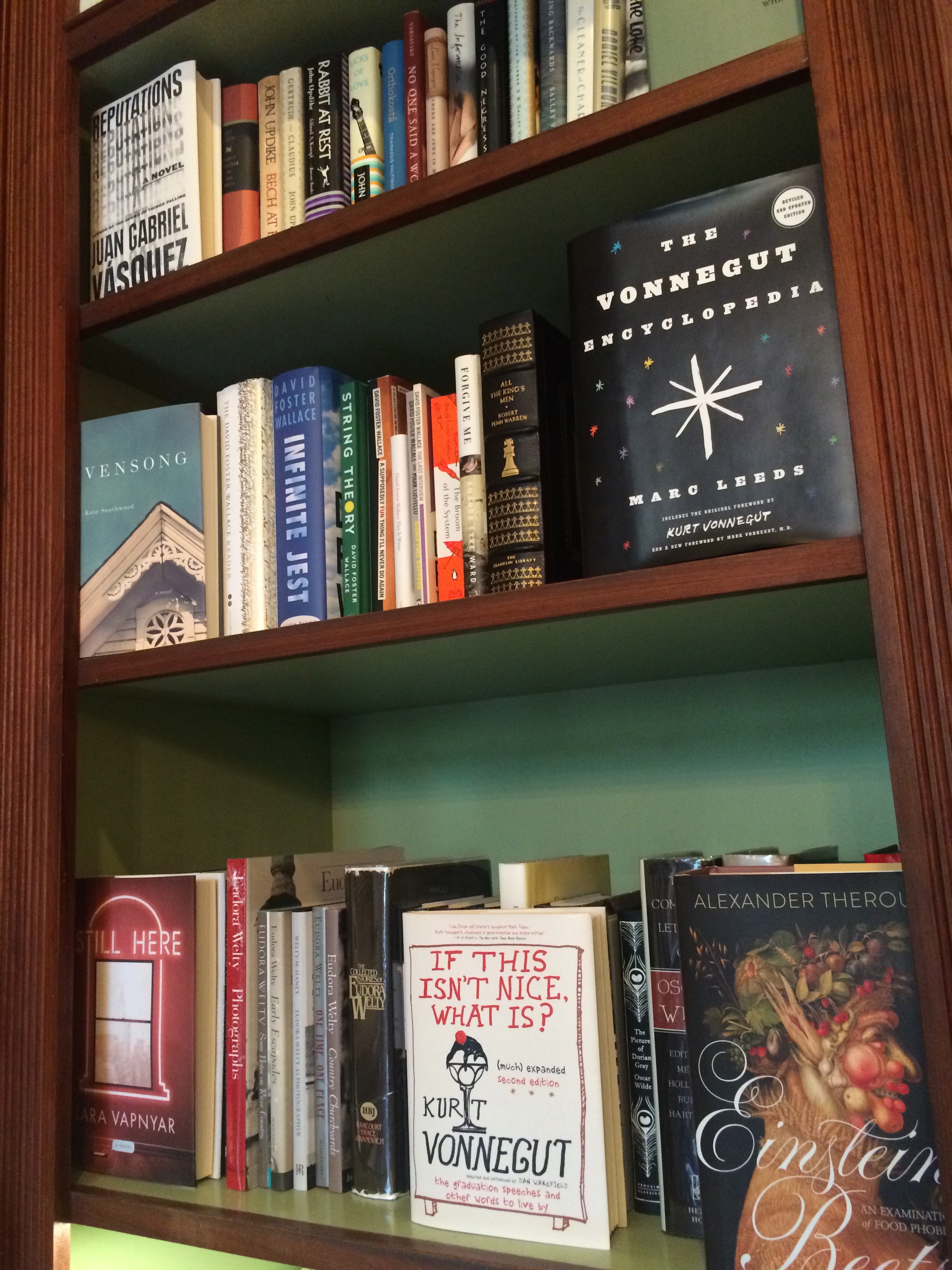

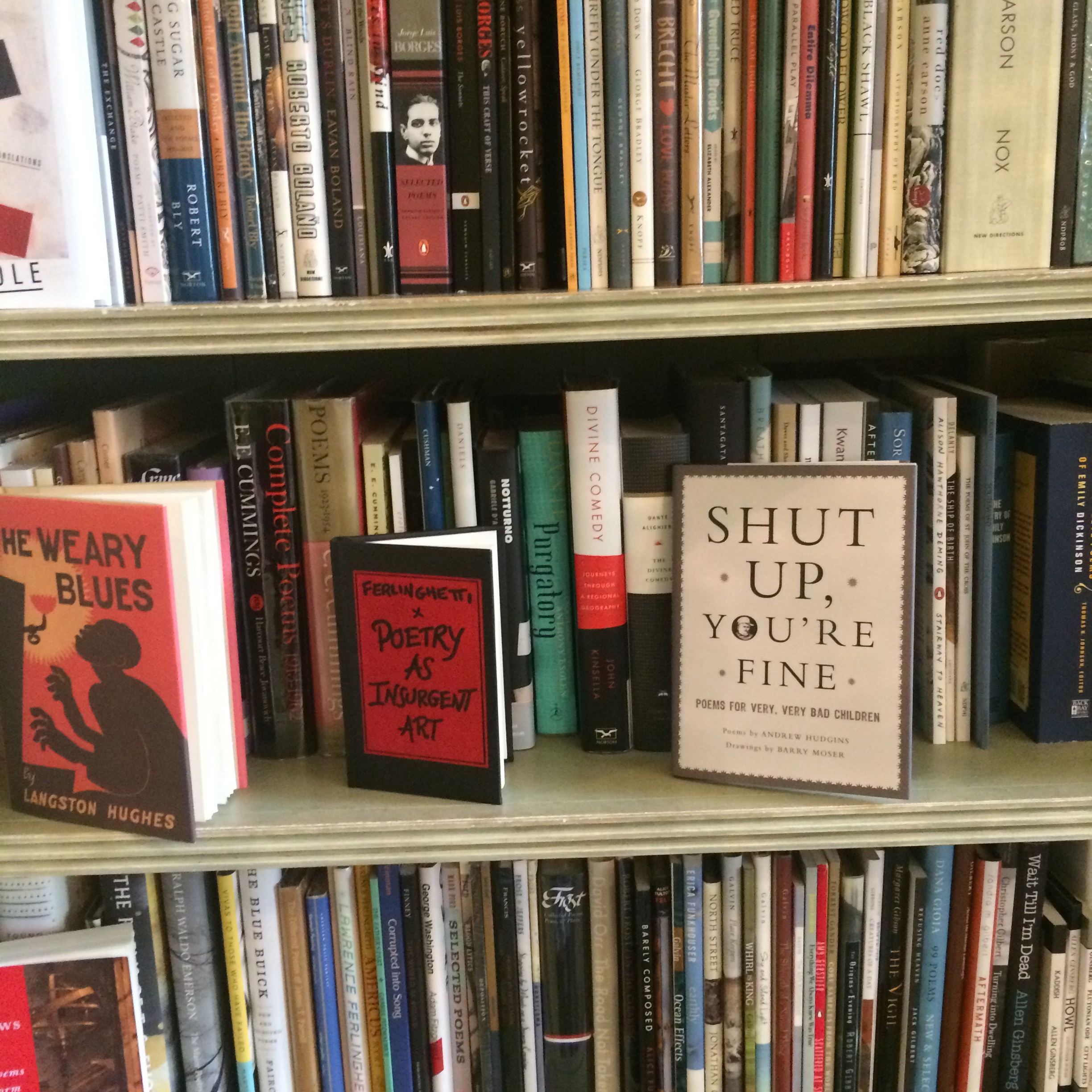

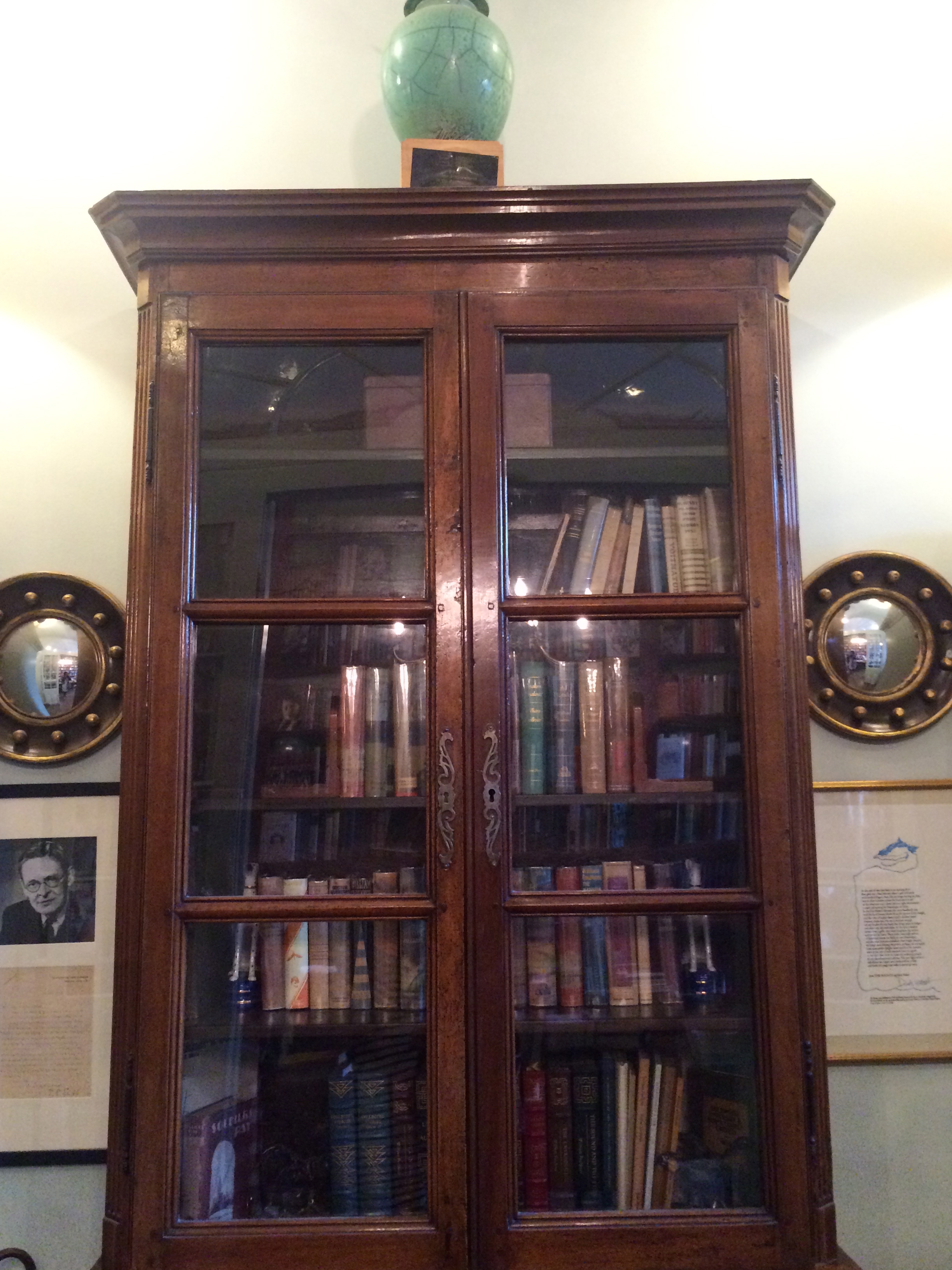

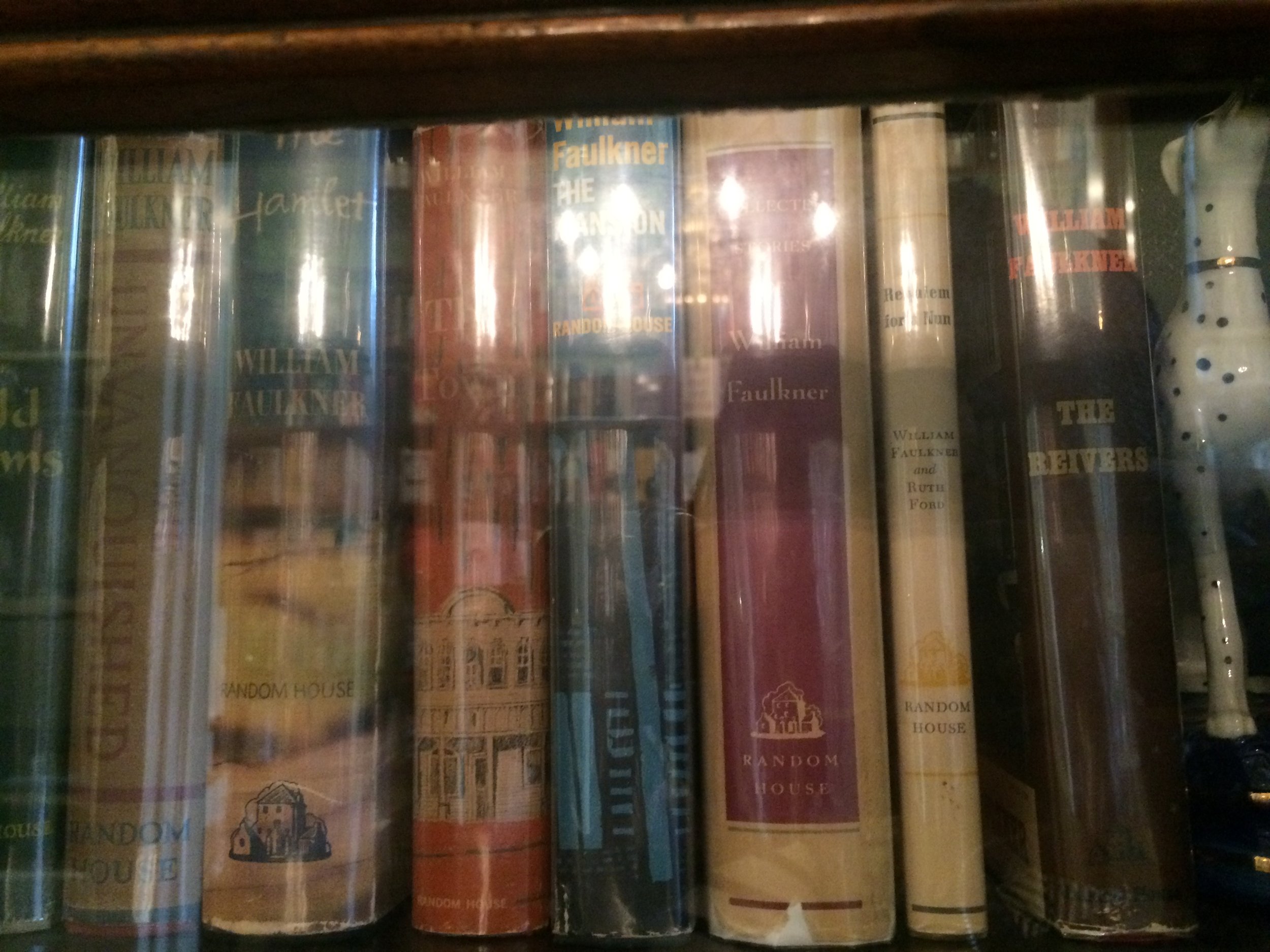

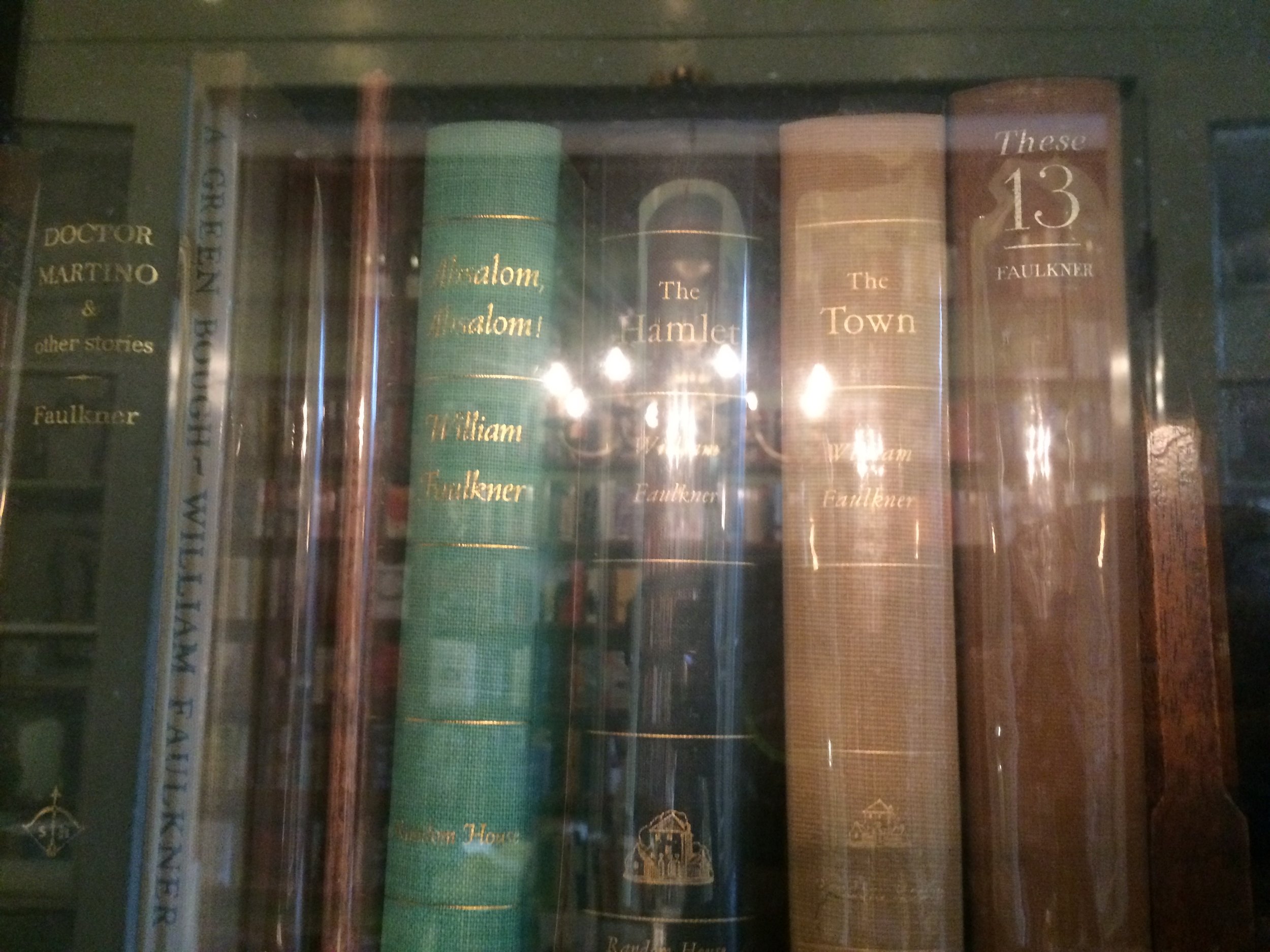

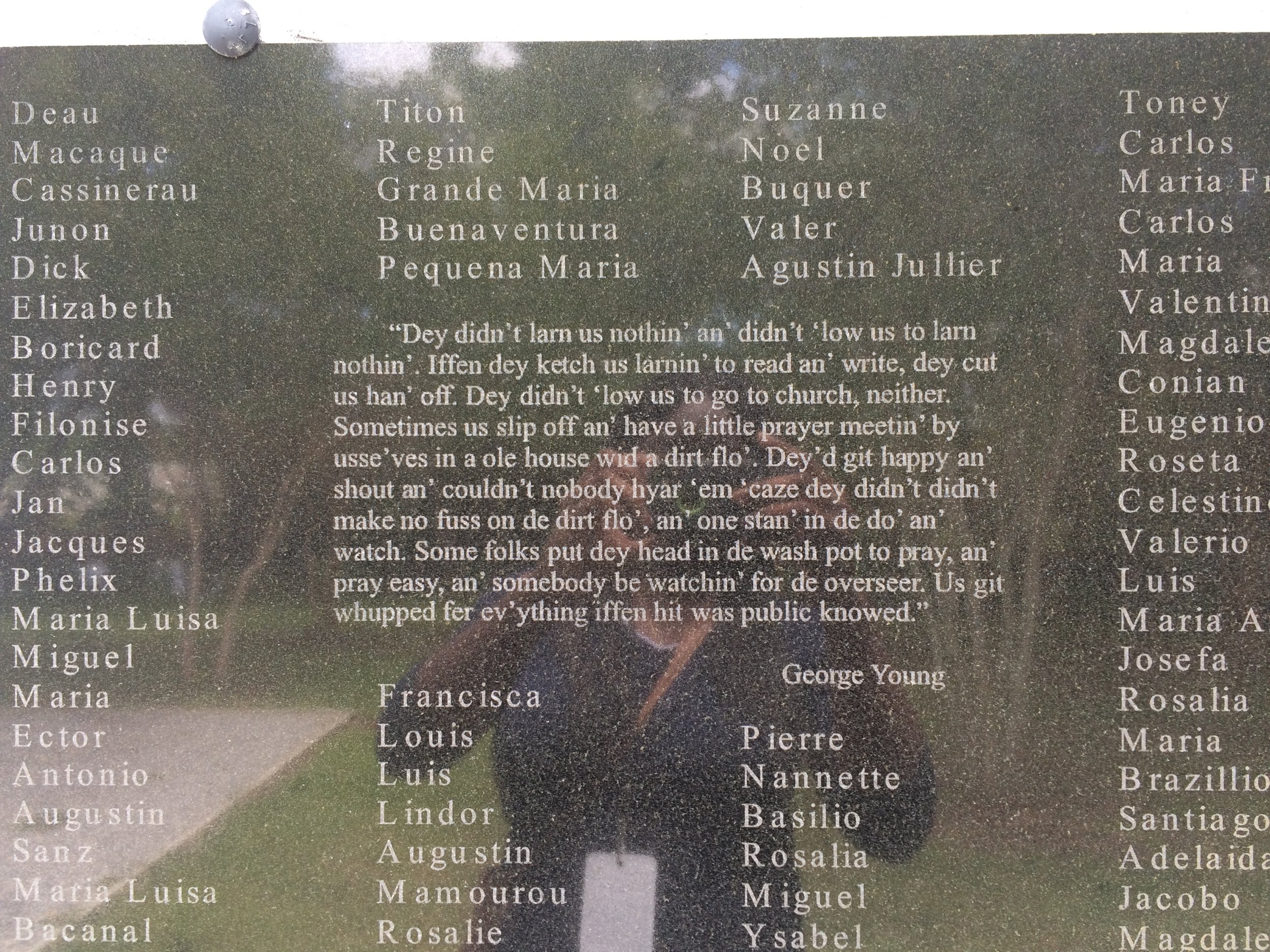

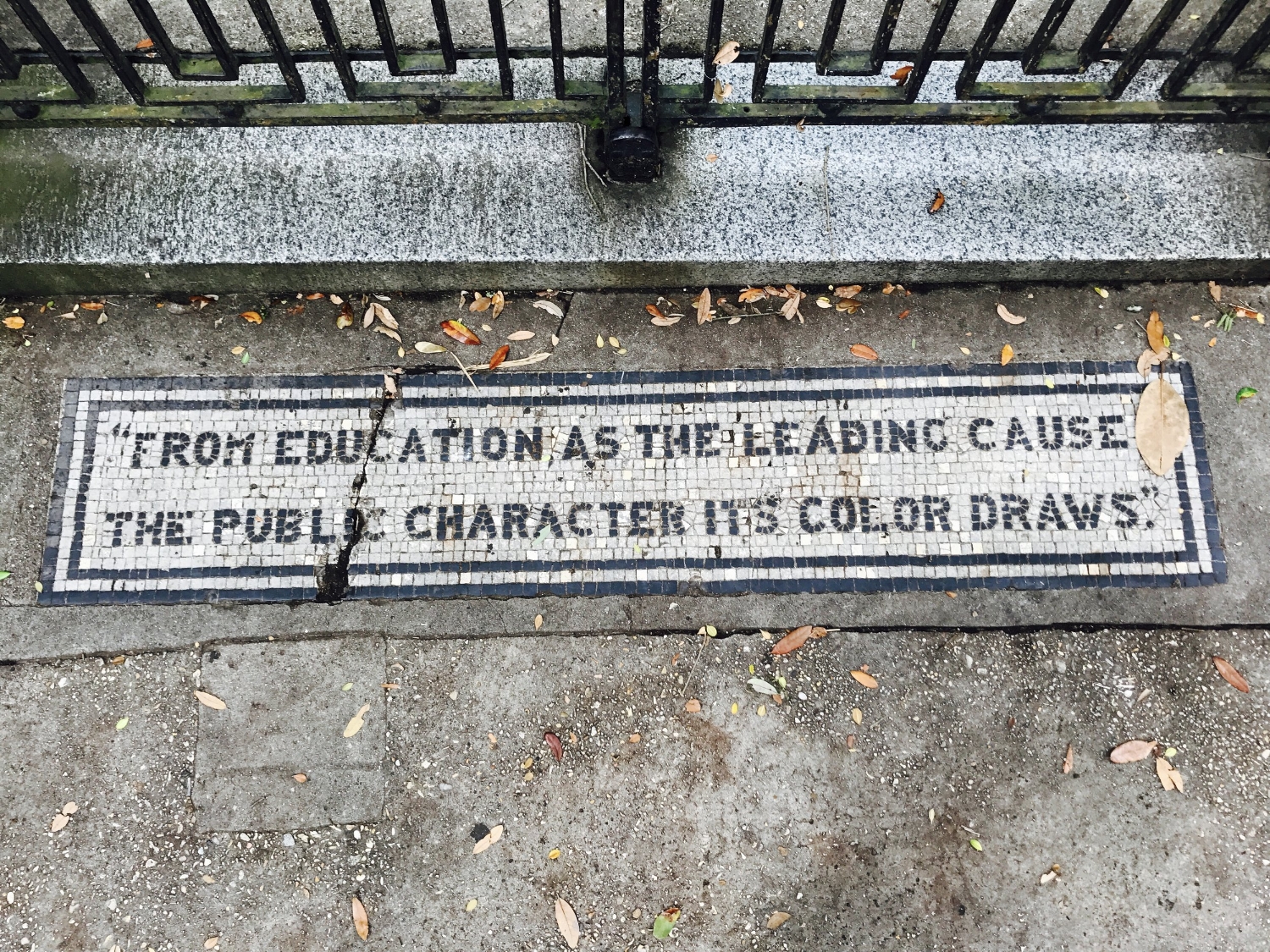

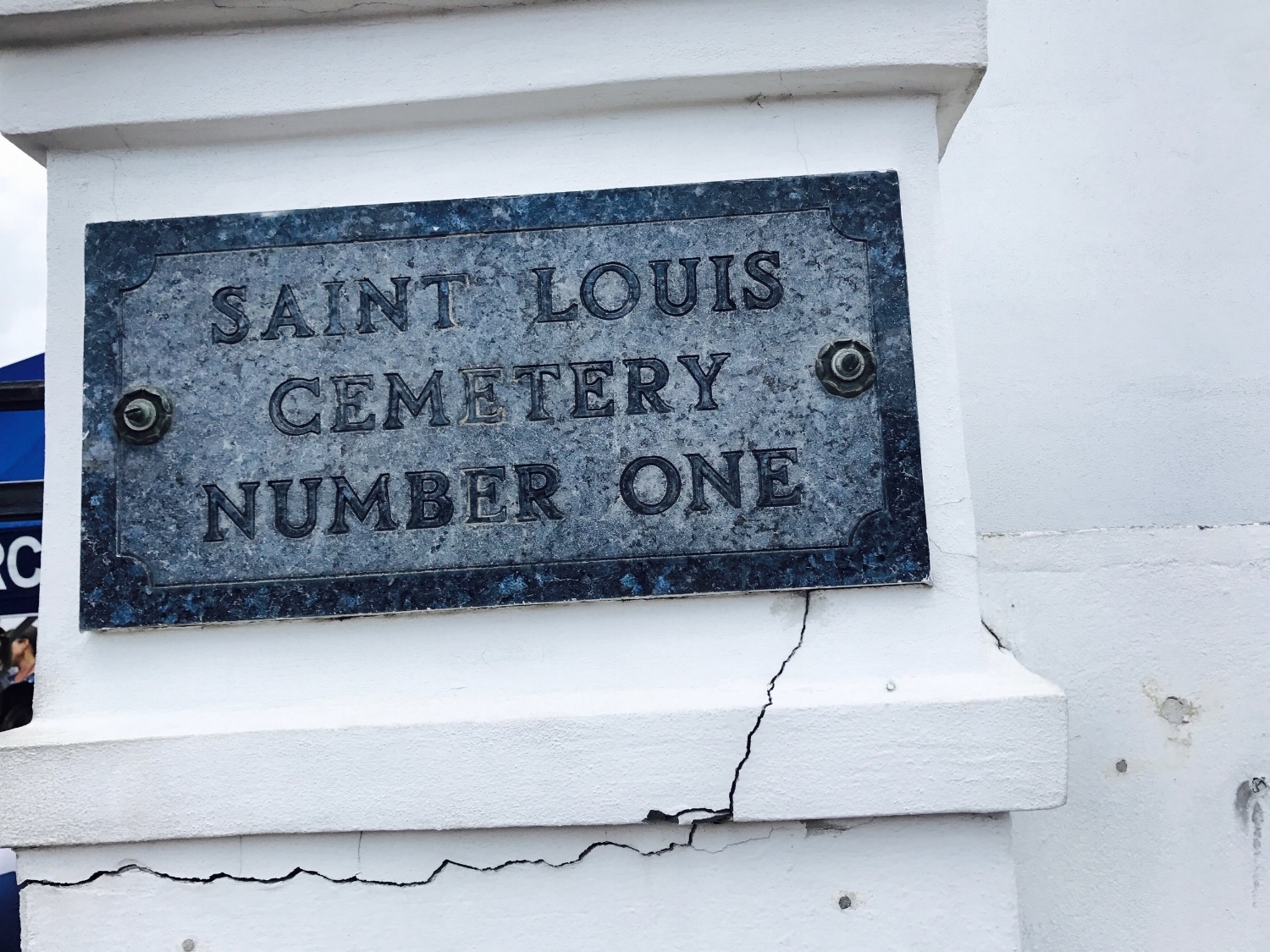

Prior to this trip, bookpacking was a new concept for me. In fact, even reading literature felt pretty foreign. (As a student in the Iovine and Young Academy, I spend most of my time with software, discussing design, and trying to create innovative products. Not much time for books.) I was a bit apprehensive of letting the books be my guide. Would the whole thing be some cheesy literature tour? How much could a book really reveal about a place? Would I miss things in Louisiana if the books led us astray? Though I cannot give a definitive answer to these questions, I do know that bookpacking has given me the opportunity to travel as Mark Twain would have. In the same way immersive discovery through food has developed my appreciation for a diverse flavor profile, immersion in literature has developed my appreciation for diversity in history and ideology and literary culture. Bookpacking has led me down roads that have been ideologically uncomfortable, challenging my own prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness. The books held nothing back. They were what they were, unchanging pillars that influenced the way I mentally pieced together the puzzle of Louisiana. As we read through each book and experienced the reality of the various cities, I began to see a clearer picture of Louisiana and Cajun/Creole culture; and in turn, I began to see a more complete image of the South and the United States. Literature in New Orleans has brought up new questions and has revealed new material I never heard in a classroom before. I definitely felt away from home, and that was good.

The return home has corresponded with the return of responsibilities. Those stresses I left behind—school projects, job search, planning for next year, and cleaning my room—they’re still here, and they’re still challenging to manage and figure out. Yet, my frame of mind approaching these small puzzles of life is different than before. The world feels a lot bigger now, and my personal decisions feel a lot smaller. And this is not just a physical reality I refer to; the world of literature adds a separate dimension. What I realized is that people have told stories about the routine of life for centuries. There is a parallel struggle of characters and people to make something new of the monotonous nature of their societies. That routine carries on today, and I am faced with this same “problem” that the characters and people of the past faced. Different cultures have tackled this obstacle in various ways. For the Big Easy, the posture is: routine life is stifling and demoralizing, so I’m going to do it my own way.

I hope that I can embrace that mindset for a long time.