“The body went to California, but the soul stayed here.”

We're leaving New Orleans today after what has been an amazing four weeks bookpacking through Louisiana. Needless to say, I’m finding it difficult to leave—the books, the people, and the food have all been wonderful.

Our bookpacking journey began with the goal of developing an understanding of southern Louisiana. By exploring literature and its historical contexts in a local setting, we hoped to develop empathy for a place that most of us were very unfamiliar with. We sought to understand what Binx, in The Moviegoer, calls the “genie-soul” of New Orleans, its nature and spirit. This is how we approached every city and town that we visited. I doubt any of us can honestly say that we’ve come to fully understand this region, but I do think that we’ve all made great strides.

Looking back on our experiences, I’ve come to frame every adventure as an examination of a myth. From the French colonial façades of the French Quarter in New Orleans to the unassuming towns in rural Cajun country, Louisiana is rife with myths. Mythology can be the foundation of an entire society’s culture, a type of pseudo-history that defines and connects people across generations. Greco-Roman mythology is the clichéd but nonetheless true example of mythology’s power to inspire art, literature, and philosophy through the span of centuries. While bookpacking largely involves reading stories in printed form, we also seek out the myths that transcend paper record. More often than not, these myths interact in curious ways with our texts and lead to great insights. In this, my final post, I want to trace some of those insights.

The trip began on the paradisiacal shores of Grand Isle, on which we flipped through the pages of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening. Chopin utilizes the history of the island and the surrounding area, especially the stories of Jean Lafitte, a pirate during the Napoleonic Wars and later the savior of New Orleans in the War of 1812. Edna spends an evening on the island of Chênière Caminada (uninhabited since an 1893 hurricane) listening to these stories, as told to her by Madame Antoine, a local who has spent years "gathering legends of the Baratarians and the sea." These legends come alive for Edna, and she hears "the whispering voices of dead men and the click of muffled gold."

Pirate tales may seem irrelevant in a story about a woman’s search for personal freedom, but the legends of Grand Isle and Jean Lafitte offer an important contrast to a myth that has long controlled Edna’s life—the myth of the perfect, docile wife. Such a figure appears in the form of Edna's friend, Adèle Ratignolle, a beautiful and dutiful "mother-woman." Chopin describes her as a "bygone heroine of romance and the fair lady of our dreams." Madame Ratignolle represents the myth of domesticity, a myth that is outdated and restrictive. The pirate legends that captivate Edna provide a way for her to free herself from the domestic myth, and she frames her romance with Robert in the style of "pirate treasure" and the "realms of the semi-celestials." Edna uses such fantasies to construct a myth in which she is empowered and in control, a proverbial pirate sailing the oceans as she pleases.

Portrait of Marie Laveau in the Voodoo Museum

Our move into New Orleans was a step into the Gothic mythos of Louisiana. Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire introduced us to the fantastical world that is almost a parallel dimension in New Orleans; it seeps into our reality through shady swamps and dim alleyways and rusted railings and mossy graveyards. Sometimes the moss needs to be cut away, as we did with the history of voodoo. This religion has been mythicized to a fault through societal superstitions about voodoo dolls and zombies, but our visit to the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum brought us to the truth of voodoo’s roots in African religions and practiced in New Orleans by such figures as Marie Laveau, whose alleged tomb we saw in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

Much of the expository action of Interview with the Vampire takes place on a plantation just beyond New Orleans. This section of the novel was a gateway into the antebellum South, an era that has certainly been mythicized into the last stronghold of romantic chivalry and gentility. A trip to the Whitney Plantation quickly dispelled this myth. Our tour brought us face to face with the deplorable reality of slavery in all its cruelty. While the plantation house certainly could have been used as a set for Gone with the Wind, the slave cabins and monuments exposed the undeniable brutality that was imposed on slaves by slave-owners. The trip was a necessary reminder that certain myths, no matter how prevalent or valued, can simply be thin veils to cover glaring truths.

This “fiddle-dee-dee” world of Scarlett O’Hara is just one of the many tropes satirized by John Kennedy Toole in A Confederacy of Dunces. The novel vividly pokes fun at the stereotypes of New Orleans, from the decadence of the French Quarter to the bumbling policeman to the blindly hypocritical intellectual, the last of which comes to life in the figure of Ignatius J. Reilly, the star of Toole’s gallery of caricaturized characters. Toole identifies mythical personalities and wittily lampoons them—in doing so, he acknowledges the truths of these myths while exposing just how ludicrous they are.

Huey Long's tomb at the Louisiana State Capitol

Ridiculousness gave way to seriousness in Baton Rouge, where we read Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. This leg of our trip demonstrated the dangerous way in which living people can become mythicized in their own lifetimes. Warren’s character of Willie Stark (Willie Talos in our edition) is based off of Huey Long, governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932. Just like his real-life counterpart, Willie uses popular appeal and fiery language to create what is essentially a cult of personality around himself. As a demagogue, Willie’s political tactics are nothing short of underhanded and corrupt. Yet, he maintains the people’s love and support. Today, Huey Long’s impact is still felt in the state—we drove across many a bridge that bore his name. Still, it is important to remember that behind the myth and legend remains a man, flawed and imperfect as all men are.

“But I always came back, and I had come back this time. I would find myself drawn back.”

The part of our bookpacking trip, however, that really put the concept of mythology into perspective for me was our sojourn in Cajun country. It was here that I found a juxtaposition of two myths that demonstrated mythology’s ability to both build and destroy.

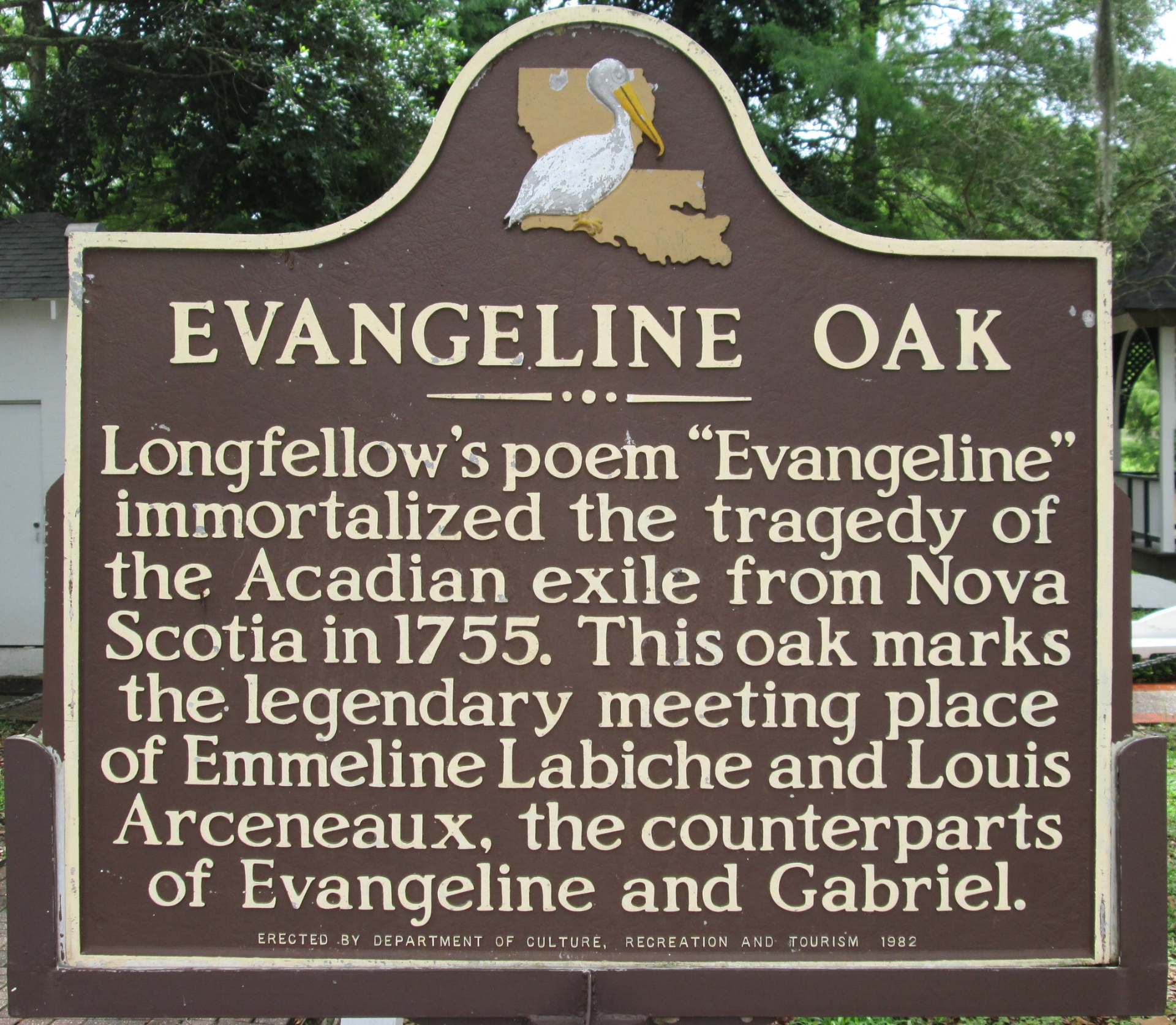

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized the story of Evangeline and Gabriel, two lovers who are separated by the British in the Great Deportation of Acadians during the Seven Years’ War. The pair’s story ends in tragedy—though they are eventually reunited, they perish in each other’s arms. Longfellow’s epic poem, titled Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie, birthed the image of the Cajun woman as a strong, longsuffering figure. It’s an image that has pervaded the regional culture ever since; we saw Evangeline’s name written on street signs, monuments, and even a restaurant here in New Orleans.

In St. Martinville, an oak tree has been designated the point of reunion for Emmeline Labiche and Louis Arceneaux, two people who may be the real-life basis for Evangeline and Gabriel. Evangeline’s story is a type of myth that blends history and fiction. In doing so, however, it has created a meaningful reality for Cajuns, who have used this legend to create and maintain a unique and vibrant culture. Evangeline is the backbone of the Cajun identity, which, as one article says, might be defined by its "romantic appeal" and "enduring spirit."

Image via amazon.com

One of our books was a collection of short stories by Tim Gautreaux. The first story, titled “Same Place, Same Things,” lends its name to the entire collection as well. In that story, Gautreaux follows Harry Lintel, a pump repairman during the Depression, as he encounters different people in a rural town in Louisiana. One of these people is Ada, a woman who at first seems to fit the Evangeline type, a simple but attractive widow in a “thin cotton housedress.” She has spent her life weathering hardships, but her beauty is resolute. Harry finds something about her alluring, maybe her kiss that tastes “of strawberry wine, hot and sweet.”

All of this is inverted in the final moments of the story. Though Gautreaux does give Ada the air of an Evangeline, he subtly weaves an undertone of darkness throughout the narrative. This darkness comes to a boil at the end, which I won’t spoil here, but Ada is shown to be far more complex than a mere trope. Her character may be similar to the Evangeline myth, but Gautreaux layers it with unique and sympathetic motivations, albeit sinister ones.

The Evangeline myth is beautiful to me. It is an integral part of Cajun culture and identity, and it has spawned great works like Gautreaux’s. There is a different myth, though, that has haunted southern Louisiana and even the country at large.

Jefferson is an African-American man who has been sentenced to death for “being at the wrong place at the wrong time.” In court, he is defended on the grounds that he is not “‘a civilized man,’” but a boy and a fool. His lawyer declares that it would be more just to “‘put a hog in the electric chair.’” So begins Ernest J. Gaines’s A Lesson Before Dying. As the novel continues, Jefferson’s godmother calls on Grant Wiggins, the local schoolteacher, to affirm Jefferson’s humanity. Grant’s initial conversations with Jefferson accomplish little, but the two eventually connect with each other. From then on, Grant helps Jefferson face death not as a subhuman animal, but as a man.

During one visit to Jefferson’s jail cell, Grant delivers a profoundly moving passage of dialogue:

“Do you know what a myth is, Jefferson? […] A myth is an old lie that people believe in. White people believe that they’re better than anyone else on earth—and that’s a myth. The last thing they ever want is to see a black man stand, and think, and show that common humanity that is in us all. They would no longer have justification for making us slaves and keeping us in the condition we are in. As long as none of us stand, they’re safe.”

[…]

“I want you to chip away at that myth by standing. I want you—yes, you—to call them liars. I want you to show them that you are as much a man—more a man than they can ever be.”

If Evangeline is a myth that uplifts an entire people, then here is a myth that seeks to oppress. It is a myth of both superiority and inferiority, and as Grant says, it is a lie, one of the most destructive ever told. This myth has generated racism, slavery, violence, and war, and even after thousands of years of human history, we have yet to shake it off. One wonders if we ever will.

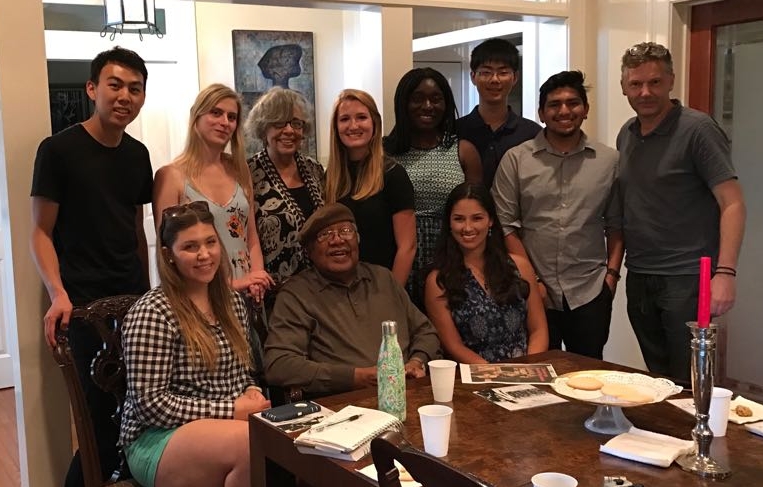

Destructive as this myth is, we can always find examples of people who defy it. Literature and art continually offer hope, as Gaines’s novel does. His story is set in an African-American sharecropping community based off of Pointe Coupée Parish and New Roads, the area in which he grew up. We had the honor of visiting Dr. Gaines in his own home, built on plantation land that he once worked and now owns. During our interview with him, he expressed his belief that great progress has been made regarding racial equality and civil rights. Even so, he also noted that there is still much to be done. Viewed in its most positive light, a negative myth can be seen as an opportunity for progressive change.

Cajun country illustrated the power of mythology more clearly than any other place we visited. The time we spent in New Roads, Lafayette, Arnaudville, Morganville, and St. Martinville put into focus the effects of cultural legends and social values and the mythologies they create. What I found most impactful was the fact that we were able to study contrasting types of myths at the same time in a localized setting—the ability to make direct comparisons facilitated critical thinking.

Of course, Cajun country is not the only region in the United States that has been mythicized. Every place has its stories and traditions, its urban legends and community beliefs. We need to approach these myths with a critical eye and consider whether they are constructive or destructive. Bookpacking’s greatness lies not in the perception of myths; rather, it lies in the ability to enact change based on those perceptions.

I’ve never stopped loving books, and may the day never come when I do. Bookpacking has renewed that love, and it has also given me a new perspective on reading and literature. This experience has turned my mind toward the myths that define my own identity and culture, the stories and beliefs that have shaped me.

Something else that I’ve realized is that the practice of bookpacking does not necessitate flying two thousand miles across the country—it can be done back home. Southern California, like Louisiana, has a wealth of relevant texts that would perfectly fit the bookpacking vision. Through historical novels like Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona or even the modern crime thrillers of James Ellroy, I can easily explore the history, “genie-spirit,” and mythology of my home region. It’s a good thing, then, that I have two months of summer left to do that!

On a final note, I want to express my gratitude to Andrew for giving me the chance to bookpack through Louisiana. I’ve had unquantifiable fun getting to know my fellow students; we’ve had some amazing times together. And to future bookpackers, I say, happy reading!