“‘This child belongs with us. She’s got Leblanc in her, and Cancienne way back, and before that, Thibodeaux.’”

After experiencing the near deadness of Baton Rouge (it felt like a contemporary ghost town, too lifeless to be a state capital), we traveled to Lafayette, the city that felt the most authentically “Louisianan” of all the cities on our journey--at least, to me it did.

I say this because it did not feel flooded with tourists, but it still had enough people for us to interact with for lengthy periods of time. The more rural, “small town” atmosphere of the city made it feel more welcoming. Our ventures into Cajun music and dancing also integrated us more into the Cajun culture.

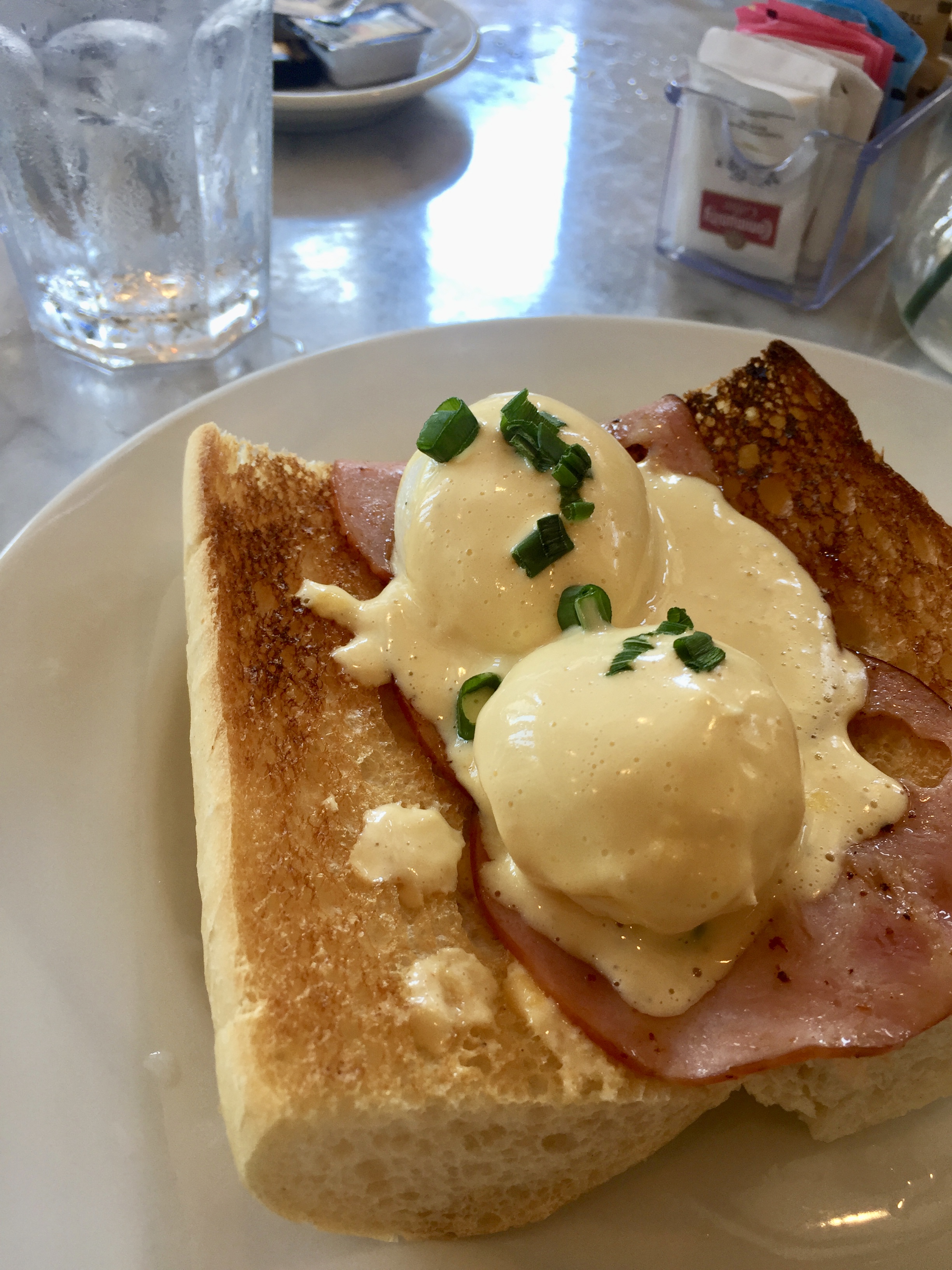

Immediately upon arriving in Lafayette, we immersed ourselves in a surrealistic world where our first meal—poboys and catfish galore—was accompanied by dancing to zydeco music. We ate at Randol’s and watched couples dance slowly around the floor, spinning and smiling, while the people around us and sitting along the fringes of the dance floor cheered and spoke to each other in their thick accents. I savored my well-seasoned catfish and watched the spectacle through the glass pane in front of me.

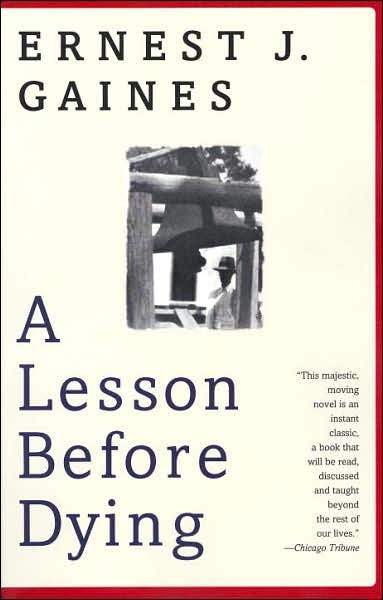

Had I read Tim Gautreaux’s short story, “Floyd’s Girl,” before this experience I likely would not have expected his characterizations of Cajun life and Cajun people to be so accurate. Yet, I read the story the day after arriving and found myself captivated by how well he had outlined his characters, showing us so much of their personalities simply through their actions and dialogue. Although I had only tasted a sample of the Cajun life, I already understood the accuracy of his depictions.

I remember as soon as we had driven into the city, I saw a car with a license plate that read “IAM KJN.” I was a little too excited to see it and I had no idea why. It gave me a great first impression of Lafayette: it signified the pride that the people had in their Cajun culture.

I think of everything Gautreaux covers in his story, he captures this pride best. He pits Floyd, T-Jean, his grandmère, Mrs. Boudreaux, and even little Lizette against the Texas man who attempts to kidnap Lizette. The antagonist’s role as a Texan proves to be vital to the story: it seems as if the act itself, while atrocious, doesn’t anger them as much as the symbolism behind the act, the idea that this man from another state, another culture, this random man is trying to take little Lizette away from the community that raised her. By carrying her off to another land, like a hurricane, he would wipe away her family, her culture, her entire lifestyle, eradicating her sense of belonging and, ultimately, her Cajun pride.

“There’s nothing wrong with west Texas, but there’s something wrong with a child living there who doesn’t belong, who will be haunted the rest of her days by memories of the ample laps of aunts, daily thunderheads rolling above flat parishes of rice and cane, the musical rattle of French, her prayers, the head-turning squawk of her uncle’s accordion, the scrape and complaint of her father’s fiddle as he serenades the backyard on weekends…”

Gautreaux structures his story by separating it into the different points of views of everyone involved—excluding the Texas man. It works perfectly in conveying the obligation everyone feels they have in helping Floyd get his daughter back: Mrs. Boudreaux letting Floyd use T-man’s car, T-jean’s grandmère’s gift of a St. Christopher statue, Nonc letting him use a plane. Gautreaux certainly hits at a togetherness in the story. The last section in the story even has the heading “Ensemble,” in which everyone works to take Lizette back from the Texas man (not one singular perspective) and announce that he wouldn’t have been able to take the culture out the girl either way.

“‘You, if you would’a went off with her, you wouldn’t have got nothing. Some things, you can’t take. All you would get is her little body. In her head every day she’d hear her daddy’s fiddle, she’d feel okra in her mouth. She’d never be where you take her to.’”

The sense of community between everyone in the story also translated into our adventures in Lafayette. These elements came through most powerfully during our trip to Tom’s Fiddle & Bow in Lafayette. I must admit that I felt uneasy beforehand, as it was a like a potluck event with music and I felt weird about bringing food and ourselves to a potluck where we knew no one.

Yet, every person there welcomed us with open arms, asking about us, about the program, about what we wanted to do. They showed us around the shop next-door and invited us to read any work we had for later that night. And, as we sat around and ate, more people walked in and joined the group in their conversations. What surprised me most was that some of these people were newcomers; like us, they had never been there before, but had wanted to join, usually with a buddy who was familiar with the gathering. Yet, they spoke to everyone as if they had known them for years. They blended right into the atmosphere of the shop.

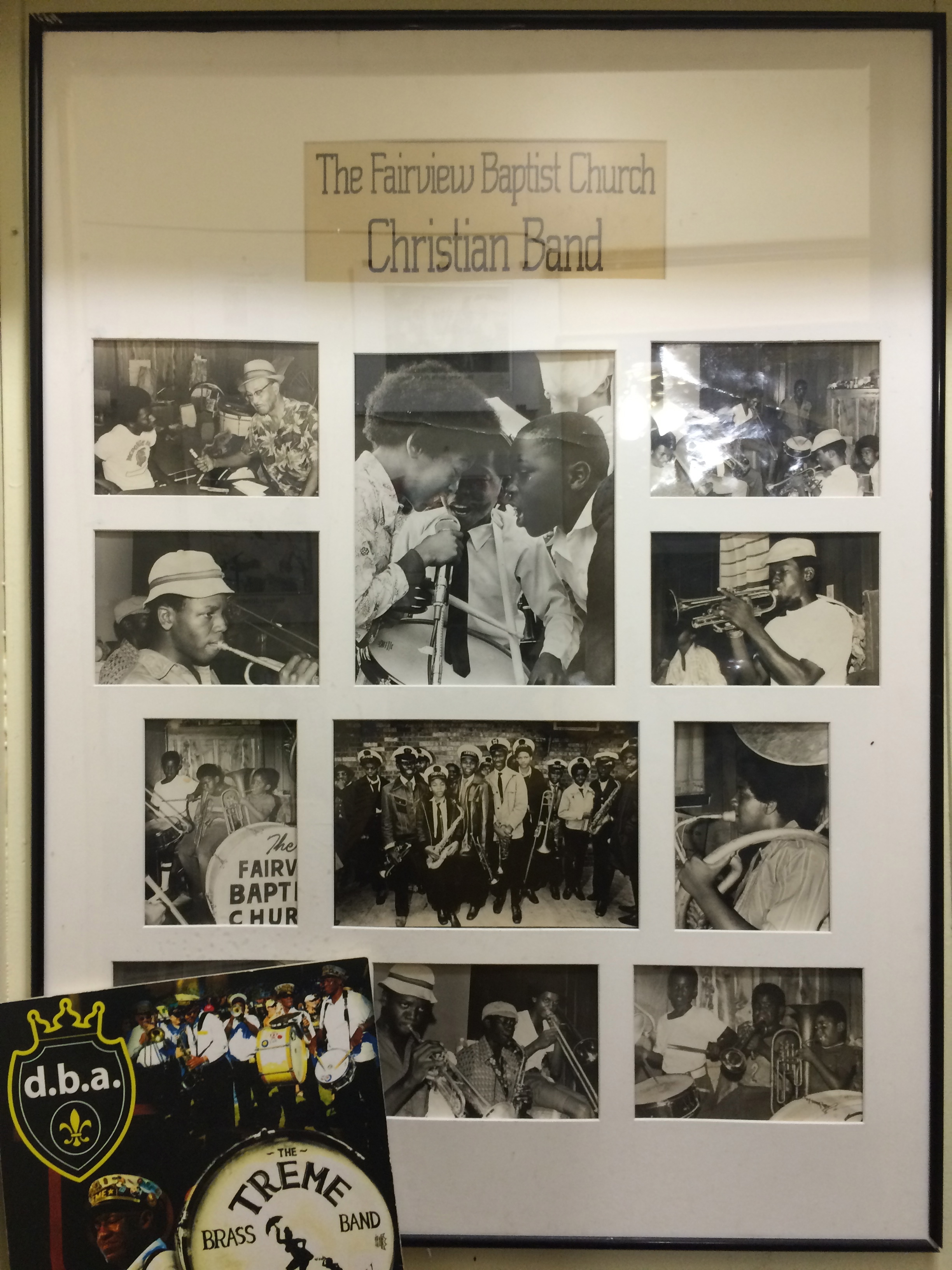

Everyone took out their instruments before long, tuning them, including themselves into the circle of chairs in the middle of the room. And soon after, everyone started playing. There was no lineup of songs, no preparations in between; people just offered up song names and the group would play, either knowing the music by heart or going along with it. It reminded me of the way my tios and tias in Mexico requested songs for the band to play at birthday parties and all danced the same Mexican dance or sang the same Spanish song. There was a clear cultural unity, customs embedded in the blood, and it was beautiful to witness.

It fit so well with the story, which I had finished by the time we visited. The way they spoke to each other at Tom’s Fiddle & Bow even felt similar to the characters in “Floyd’s Girl.” But, it was those themes of togetherness and pride that seemed to shine through the most, in the story and in the fiddle shop. It was perhaps one of the greatest glimpses of the power that literature has in capturing the essence of a place; not just the landscape, the street names, the prevalent food, but the atmosphere, the tone.

I felt like this was confirmed during one of our conversations with one of the fiddle players at Tom’s Fiddle & Bow, Joel (who also had an awesome voice). Chipping into the conversation we were having with some other folks about writers who focus on the bayou and Cajun life, he asked if we had read Tim Gautreaux yet. I said that we had just finished reading a story of his and he responded, saying that he felt Gautreaux was the man who captured Cajun people and Cajun life the best. Although I had already begun to see the similarity beween Gautreaux’s story and the atmosphere of Lafayette, hearing a local confirm the accuracy of his writing made it feel even more enlightening.

While Lafayette didn’t have the flashiness of the French quarter or the carefree relaxation of Grand Isle, it provided some of the most enriching experiences during our trip, some of the best glimpses into the customs and characteristics that distinguish Louisiana from every other part of the United States (and even the world).