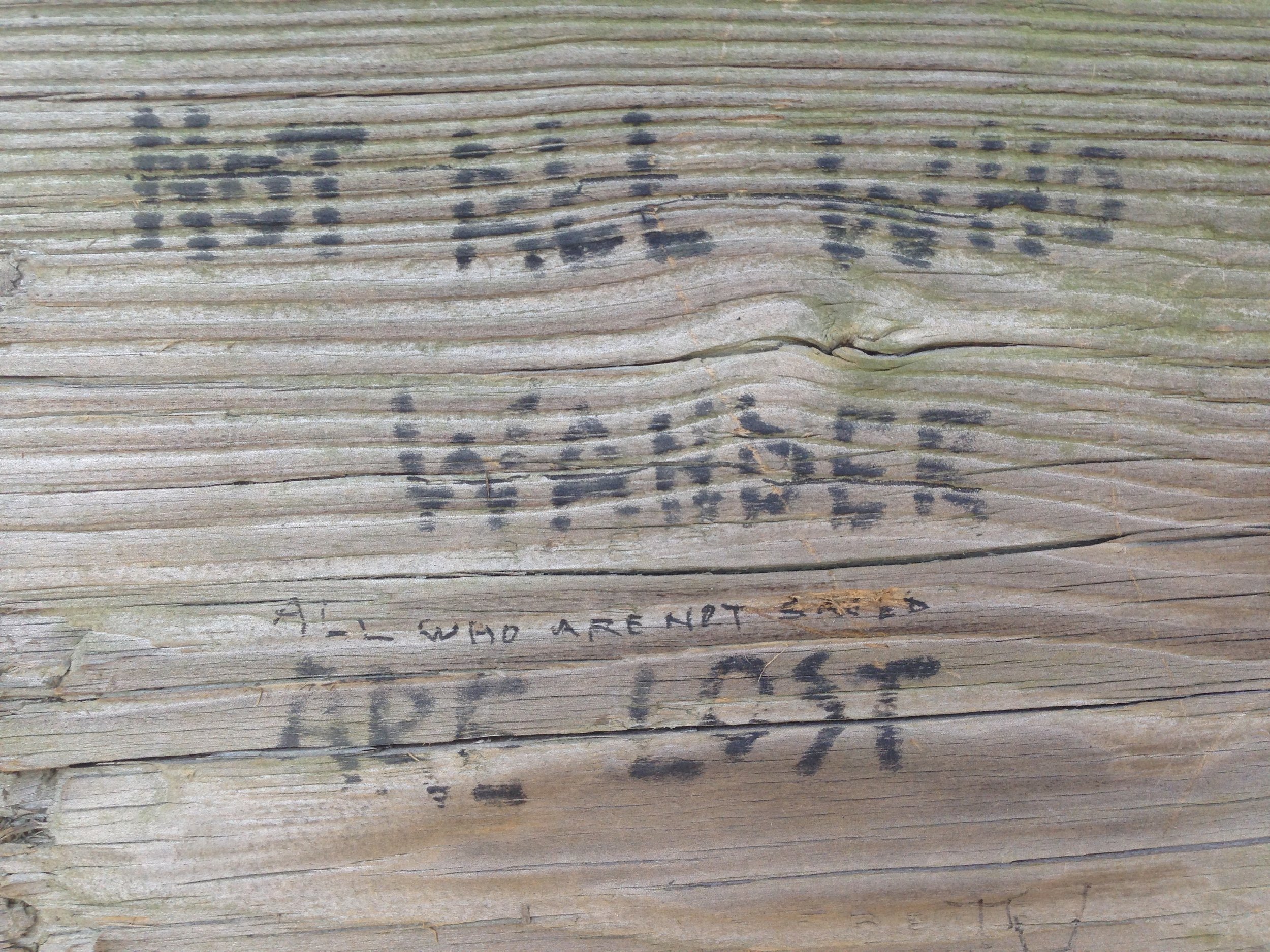

After a long night of restaurant hopping and millennial excursions, my fellow bookpackers and I landed ourselves in the middle of the spectacle that was the Confederate protest against the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue. The night was ripe with heated political exchanges and the energy emanating from the small Southern crowd around the square made everyone nervous and giddy for movement. We had just arrived two hours before midnight when the statue was scheduled for removal. Despite the fear that a race riot would erupt, the crowd was anticipating the statue's removal because for the first time in 166 years, New Orleans was doing something about its somnubulent Southern past by tearing down a Confederate relic of white supremacy.

As a sojourner to the South and native Californian, I was afraid that the situation would escallate into violence and belligerent racist protestors. Nonetheless, we slowly dawdled our way toward the crowd. I grew more comfortable by the relative composure of the crowd in relation to the few beer guzzling, racist hollering protestors who made a ruckus in the front area near the statue. Inside Lee's circle, we saw various New Orleanian residents, people from other Southern states, newsreporters, and folks from all over the country discussing whether the city should retain the statue in the circle. The Confederate flag was mounted in the front by protestors who came from Mississippi and Alabama. Clearly, these protestors were staunch in their belief that they new what was best for the city of New Orleans by declaring that the city should maintain the statue in order to retain their Confederate image.

The scene was hot with intensive discussions, political banters, and an unsettling sense of progress for the city of New Orleans. Afterall, New Orleans is known for its rich history and regarded as the Southern melting pot wherein whites, blacks, Native Americans, and people of color in general coexist more smoothly compared to other cities in the United States. While the rest of the group explored different parts of the square, I approached these three black women from the Bay Area (my region of California) named Fatima, Selma, and Sonya and two other white women who include Charlotte and Annette from another neighboring Southern state. The women were having a conversation about Southern history. With their consent, they allowed me to interview them and record their earnest perspectives on Southern history and the Lee statue.

Lee Statue Interview

Ogechi: What's your perspective on the demolition of the Lee Statue?

Fatima: I don't believe in destroying history under any circumstances, but I do believe that the statue needs to be taken down.

Selma: So we're sisters and our mom is an archivist. She supports the preservation of history and as she says, "The statue should be put into a museum and put into context so people can understand that this is apart of history and a bad part of history."

Fatima & Selma: But the statue shouldn't be placed up here as a symbol for the Confederacy and white supremacy.

Ogechi: What do you know about the statue's history here in New Orleans?

Sonya: Robert E. Lee was a general who fought to preserve the status quo of the African slave so the South can profit off of slavery. He lost the war and he was a traitor. This is a statue that symbolizes a false sense of superiority for Europeans, which they don't want to know. If whites looked at their history, they would be aghast and they've been taught this false narrative for so long. Robert E. Lee was not a hero.

Ogechi: What will be the impact of the statue's removal on the city?

Fatima: There won't be any impact. Most of the people who are here are from out of state. There won't be any negative ramifications for them.

Charlotte: Personally, I'm from out of state and I came here tonight because it does impact me. I came out here because I wanted to witness and learn more about my history. Now that I'm hearing your perspectives, I want the statue to come down because I don't want this symbol to stand up here for people to see. I wouldn't even want to see this symbol while driving to work.

Fatima: The visceral reaction that's caused by the Confederate flag and the statue as a symbol of the Confederacy is bad. I went to high school in the city and I took the streetcar that runs through this square and had to see this monument every day at my underfunded public school. It was just an extension of the oppression people are facing. I think it would be nice to have little black kids in New Orleans today not have to see these symbols.

Sonya: If you grew up in this system and were told each day that black is bad, you can't go to this restaurant, and all you have are all of these reminders of what happened to you, then it causes a lot of post traumatic stress. As a 57 year old person, my peers still have the memory of segregation. Even now as we look at history books, all they tell me about my people is that we were slaves. Now I teach history and I give back with that subject so that kids can grow up with a sense of self and pride knowing the real history.

Ogechi: What would you say to the supporters of the Confederacy who still hold onto the nostalgic dream of the Southern past?

Charlotte: I do wear things with the Confederate flag on it, but it doesn't have anything to do that. I don't care about what color you are and I treat everyone the way I want to be treated. I just wear it because its a part of my Southern heritage.

Sonya: Do you know what you inherited? You inherited a history steeped in rape, murder, and every degredated and oppressive type of crime that can possibly be bestowed upon a person. This isn't to say that there hasn't been slavery in other parts of the world because every culture and country has conducted slavery. What is it inside a person that can treat a human that way?

Charlotte: My family personally never owned slaves or endorsed anything that supported slavery.

Sonya: Yet, you guys are still benefiting from what happened to us. What I would say to the older generation is put yourselves in our shoes.

Charlotte: I do try to understand. I come from a predominately black community so I am a minority in my own right and I'm fine with it. I have enjoyed getting to know the people I've gone to school with the past 18 years.

Sonya: Knowing that I know everything that happened to my ancestors, I know that I shouldn't be where I am because I have a doctorate in sports management. Some people wonder how'd I get here. What's interesting is if you had told me you had the same degree, I would have said well of course you do. There would be no reason to envy any European that has money or had the same level of education. Of course you do. You have not been processed through this system the way African-Americans have. When I see people like Colin Powell or people like myself, the African-American women who is the most educated group of educators in North America. How did that happen with the beginning that we had? Yet, still we have to preserve in order to become what we are.

You can here more of Sonya and Charlotte's conversation in the audio provided below: