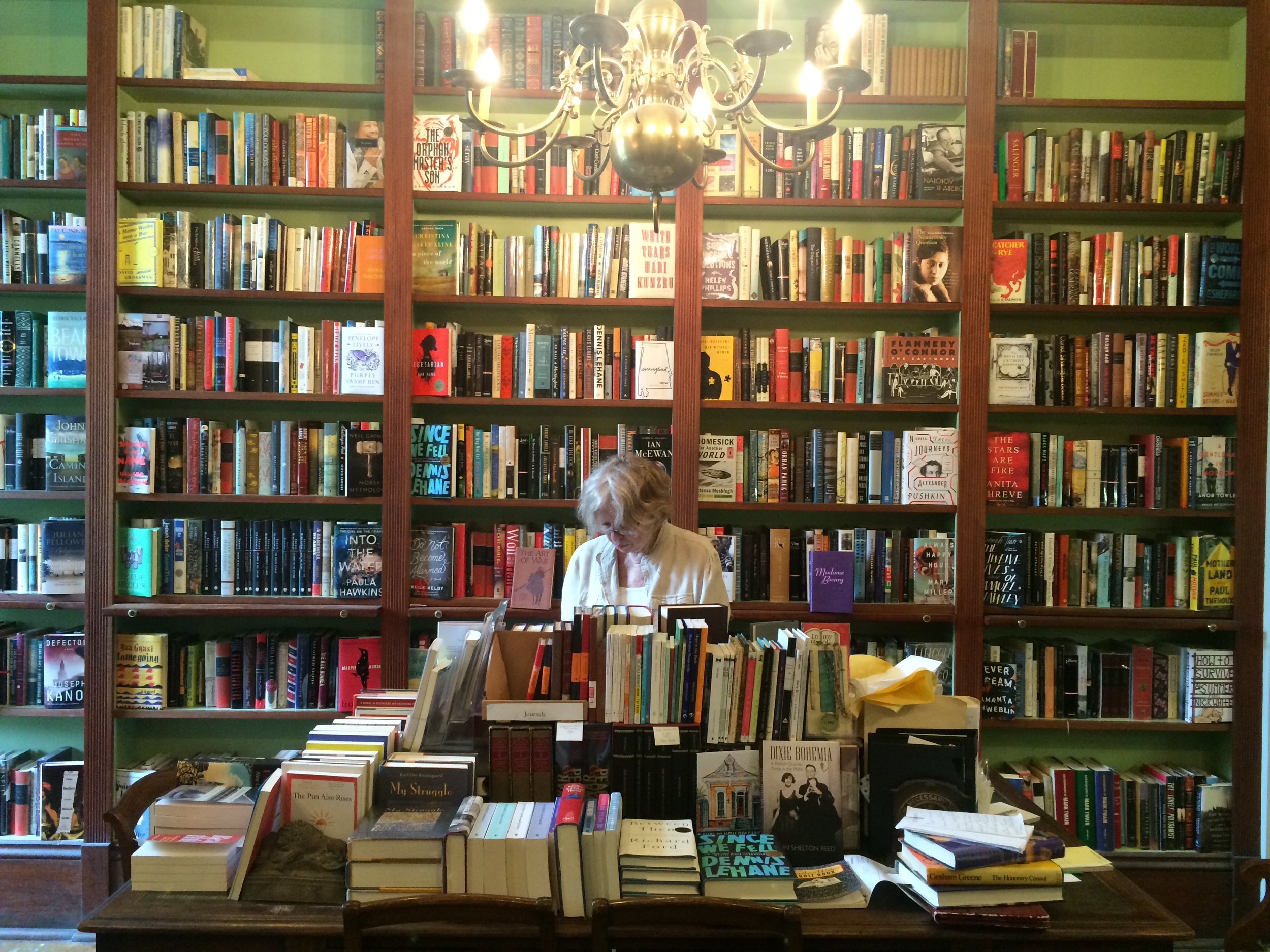

The Faulkner Bookstore is a bookstore for septuagenarians. I mean it. The Faulkner Bookstore is like the heavyweight champion of all bookstores. Almost every classical book of literature is heavy, bounded with hard-cover leather, and sheathed with elaborate golden pages. The store is wedged in a back alleyway behind the St. Louis Cathedral. When you first come across the Faulkner bookstore, you can find the lovely pedantic baby blue entrance doors and the modest emblem of the Faulkner logo. The doors looked magical and evoked a calm, inviting gesture leading into a fancy display of Southern Gothic literature, American classics, and my favorite works of contemporary nonfiction.

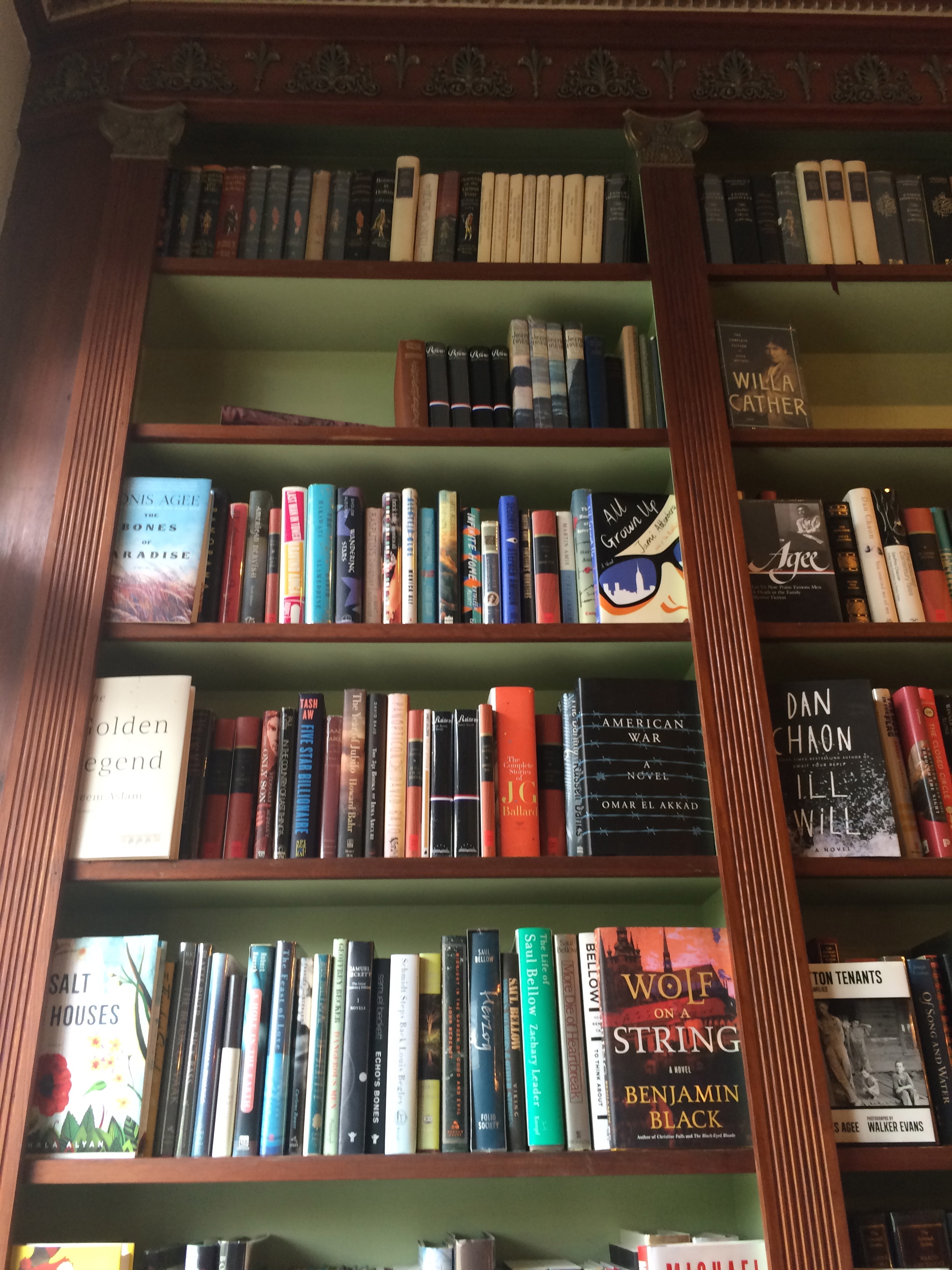

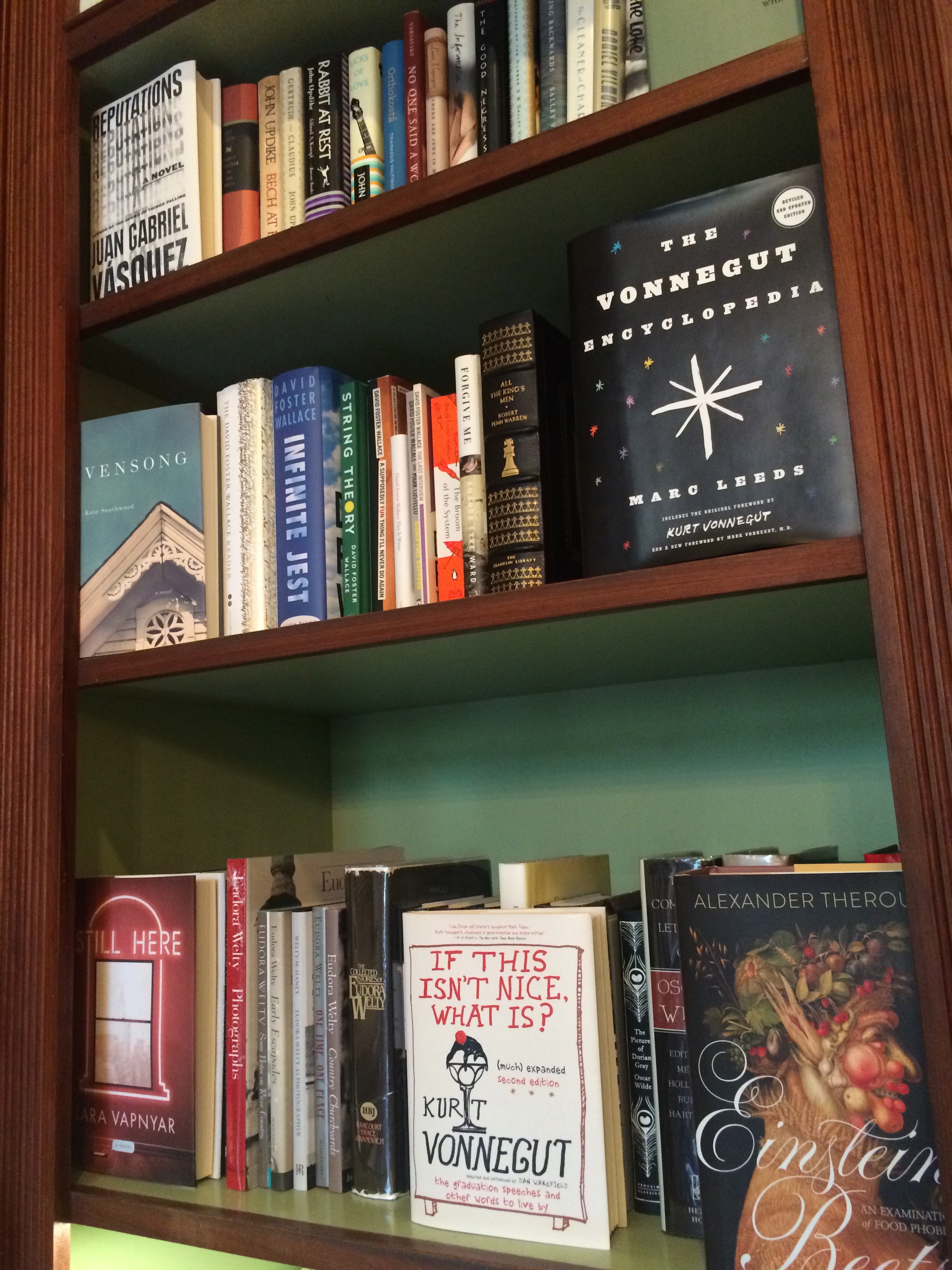

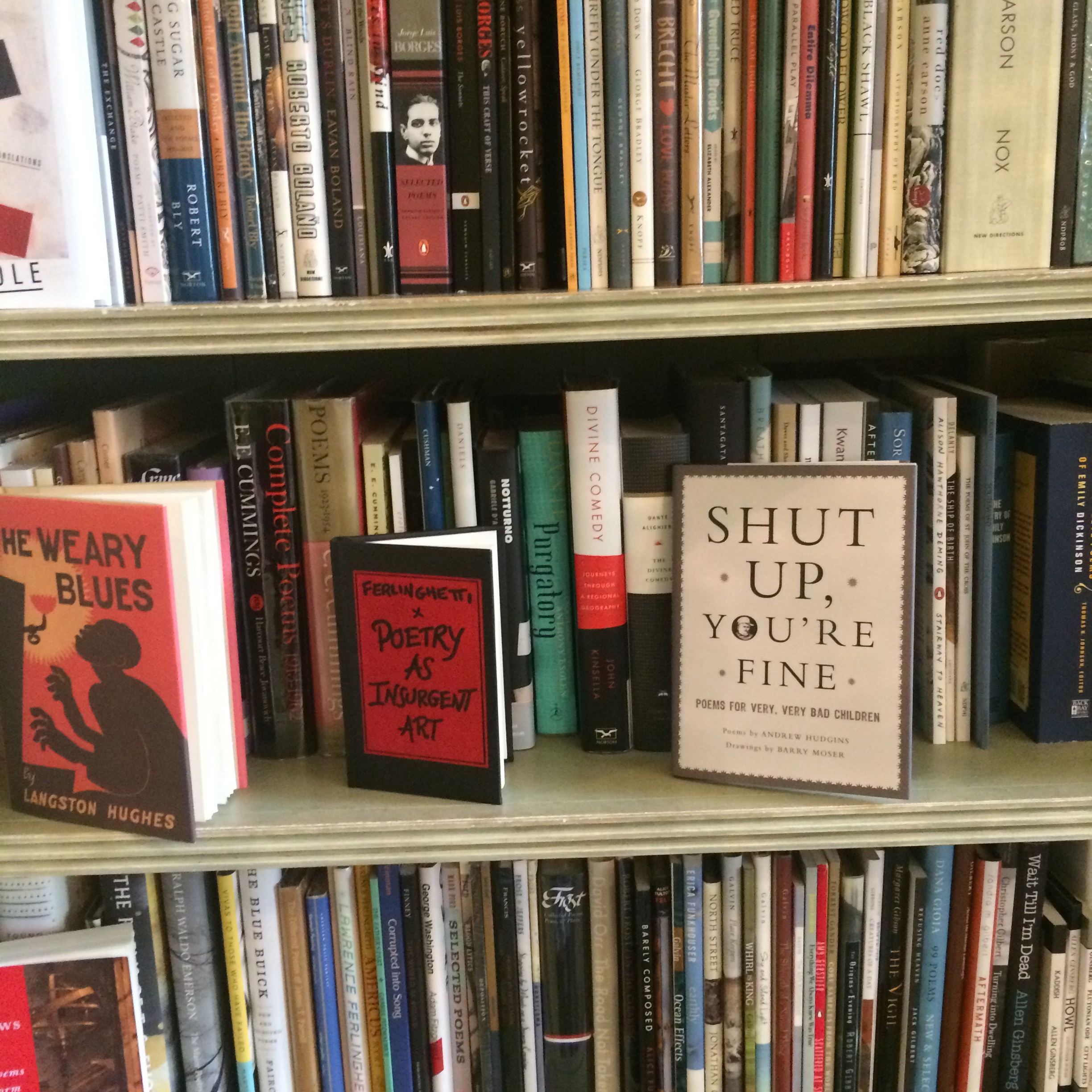

Inside the bookstore, wooden bookshelves contain large, colorful volumes of contemporary reads and rare books. The first thing I noticed about the selection of books on the shelves was the careful balance between classical literature, works of art, and contemporary fiction/nonfiction for mature readers. Unfortunately, most book prices spann anywhere between $15-$60 per book, which added to the bourgeois atmosphere of the bookstore. Everything in the store was simply so expensive, but incredibly enticing.

“Whenever I feel bad, I go to the library and read controversial periodicals. Though I do not know whether I am a liberal or a conservative, I am nevertheless enlivened by the hatred which one bears the other. In fact, this hatred strikes me as one of the few signs of life remaining in the world.”

Reflecting on Walker Percy's novel, The Moviegoer, I do resonate with John "Binx" Bolling's retreat into the world of books and quiet introspection. Although most of my peers disliked The Moviegoer and Bolling's self-absorbed quest to resign into mundane life, I believe this novel carries a very powerful message about the interior of the American psyche and way of life. Binx's prides himself on being a model citizen from the Southern genteel class. He enjoys watching and re-watching movies, hooking up with girls, pushing boundaries, and contributing very little to society. In doing so, he alienates himself from his friends and family and silently rejects his Aunt Emily's prodding to be more ambitious. In many ways, Binx's lifestyle demonstrates that atomized American way of life that lacks a spiritual foundation, moral fiber, and provincialism that cannot self-reflect in an transcendent manner.

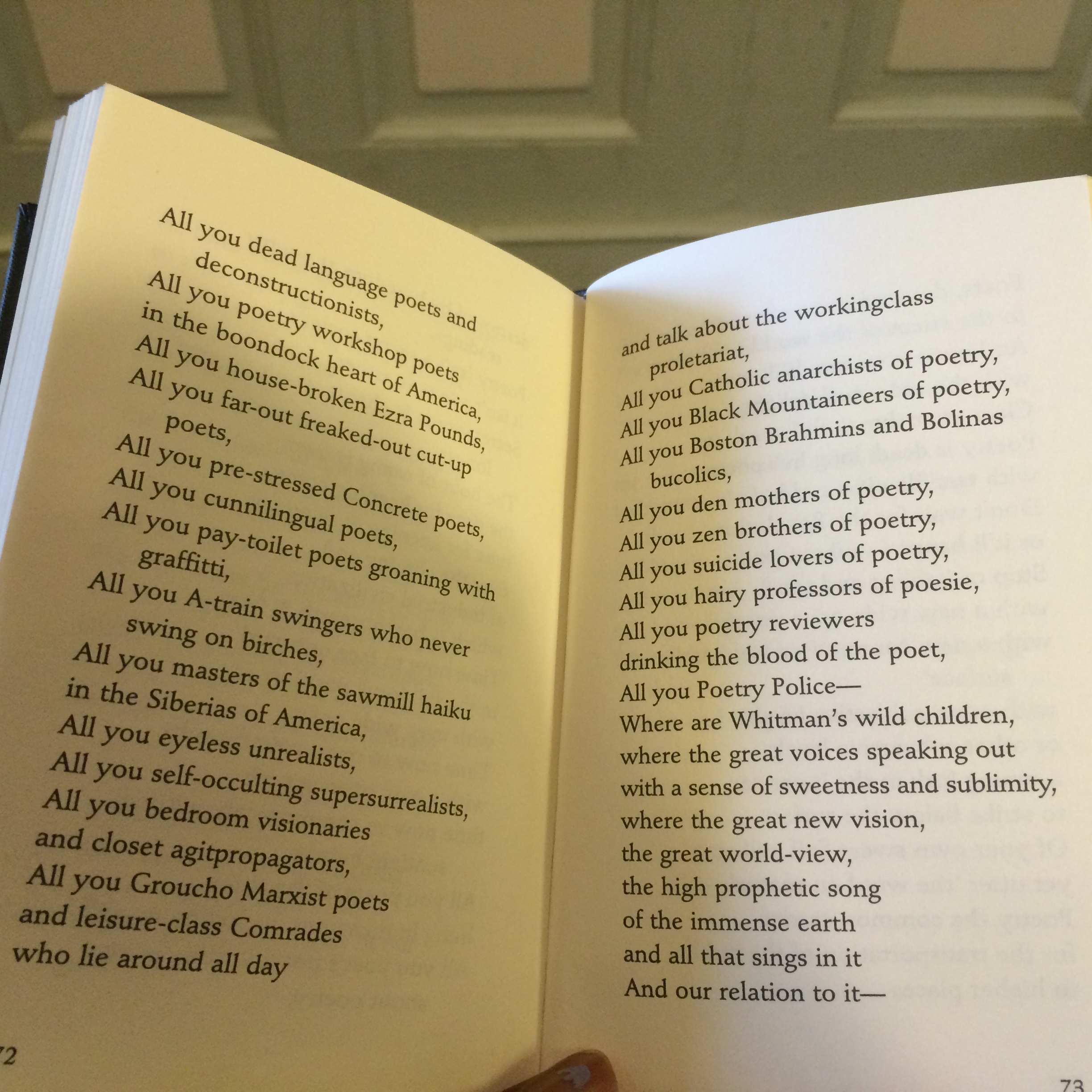

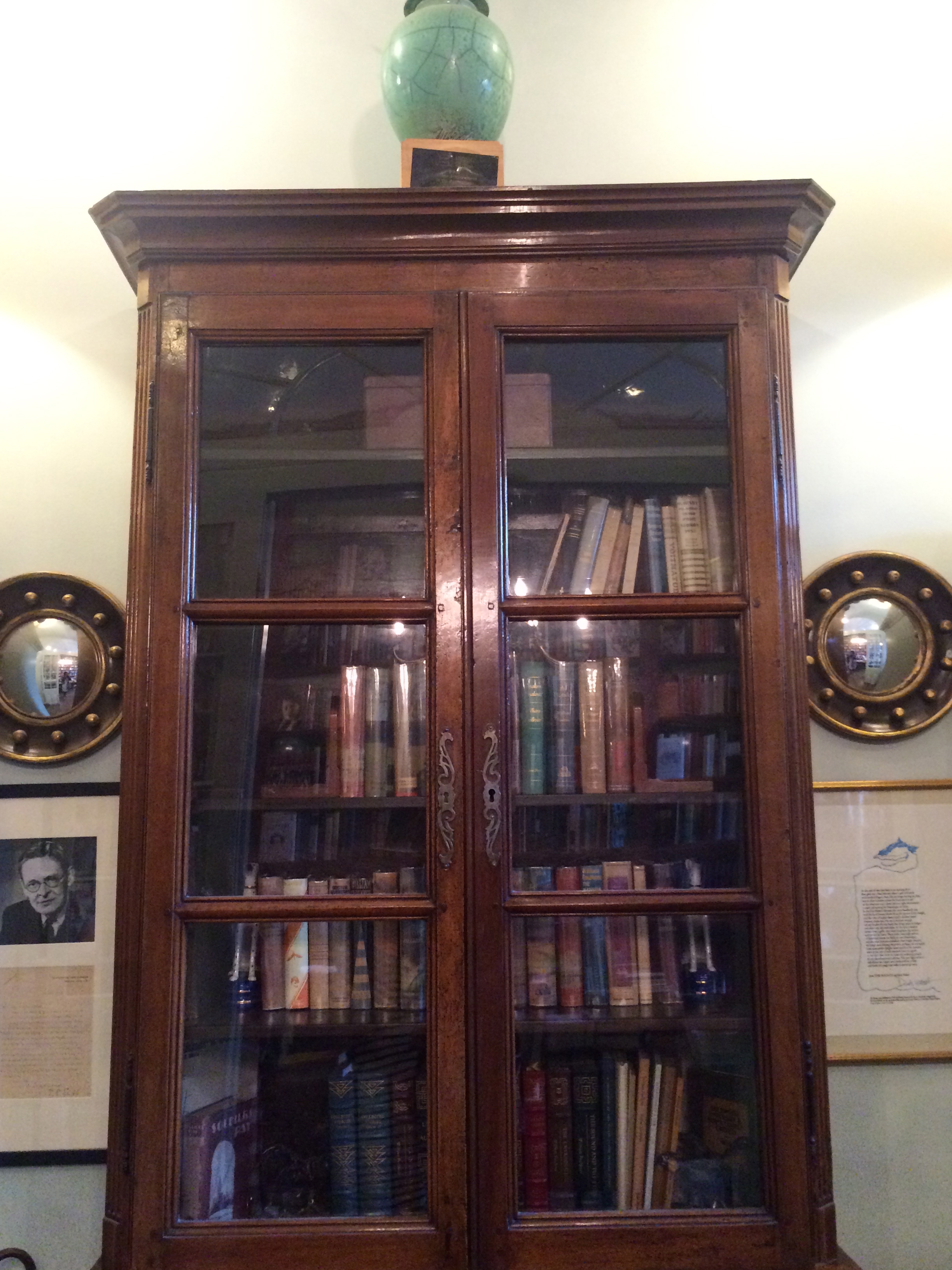

Binx struggles to establish his sense of self and add spiritual definition to his life. He doesn't want simply live up to the standards of his Southern genteel heritage. This is why I think there's a bit of the moviegoer in all of us. Despite Binx's childishness, he redeems himself by burying his head in literature that challenges him to search for meaning outside of what's already familiar to him in daily life. Even though I don't believe literature is the universal solvent for remedying the effects of emptiness, spiritual deadness, or alienation, I do believe there's an immense wisdom to be gained from reading books written by authors who were able to look at society from an outsider's perspective and forage meaning from it. So on, I pressed forward to William Faulkner's book collection and poetry bookshelves in the corner room to extrapolate meaning for myself. Just being around Faulkner's books gave me an unduly sense of stability and rootedness in the present.

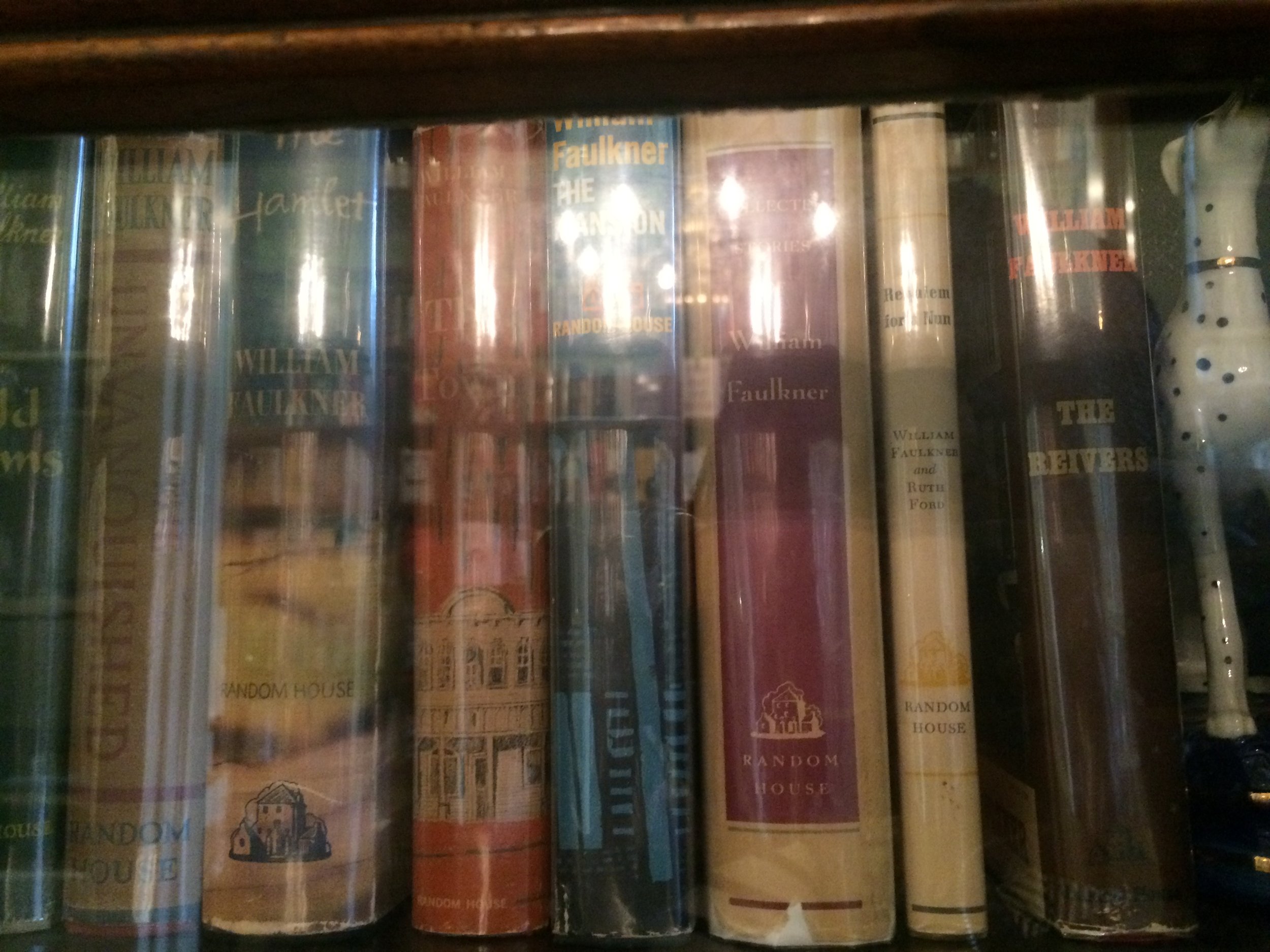

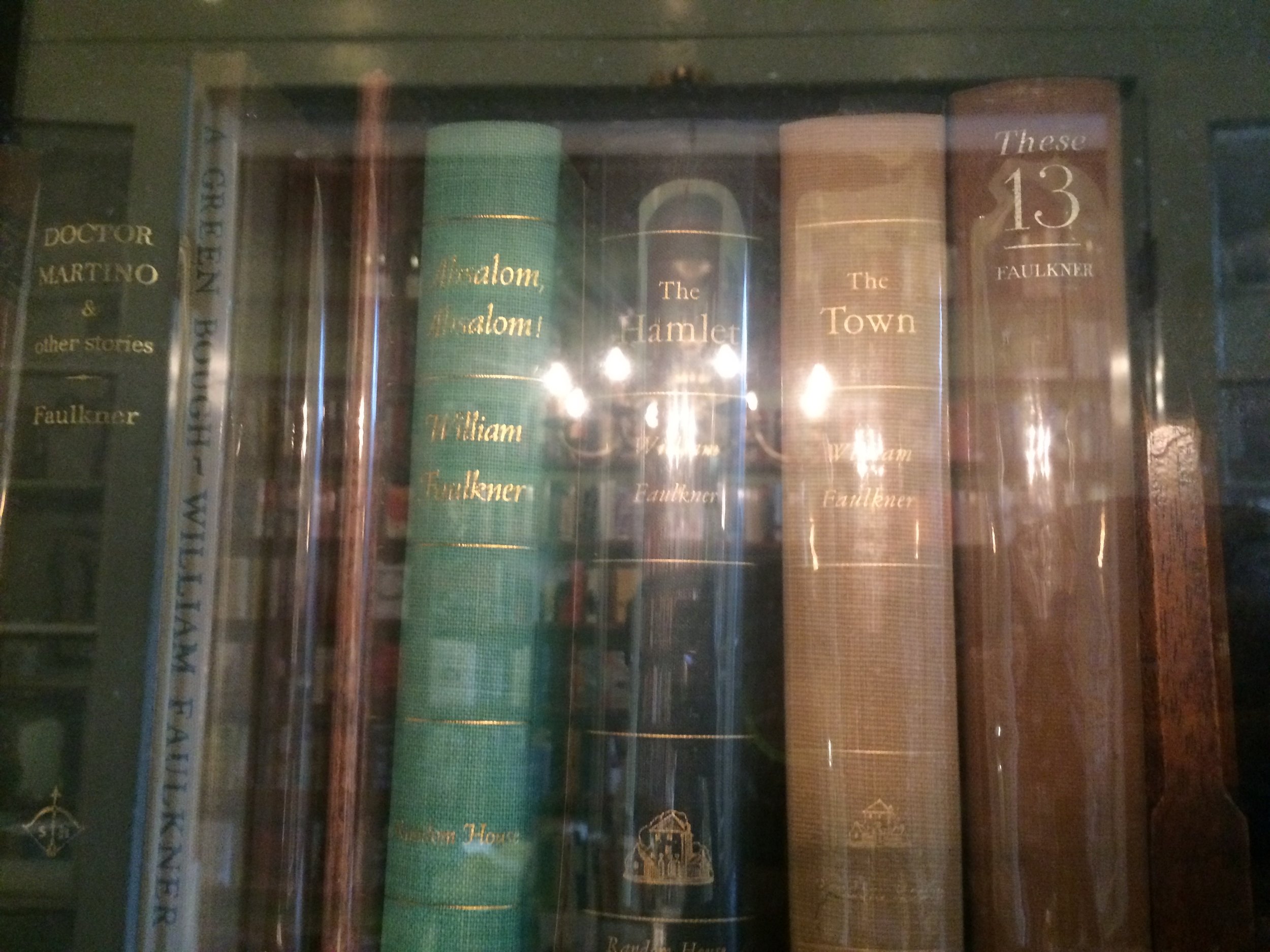

Walker Percy and his friend Shelby Foote, the famous Civil War historian, traveled to Oxford, Mississippi to speak with Faulkner after Percy graduated from college. Percy was stunned by Faulkner's genius to the extent that he said very little during their meetings. Many famous Southern writers such as Percy's friend, Shelby Foote, Robert Kennedy Toole, and Robert Penn Warren were all inspired by Faulkner's Southern gothic style and inclusion of the supernatural. The bookstore possessed some treasured rare editions of Faulkner's works that include: The Town, The Hamlet, Doctor Martino, The Sound and the Fury, These 13, Absalom, Absalom, Intruder in the Dust, and The Mansion.

“The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.”

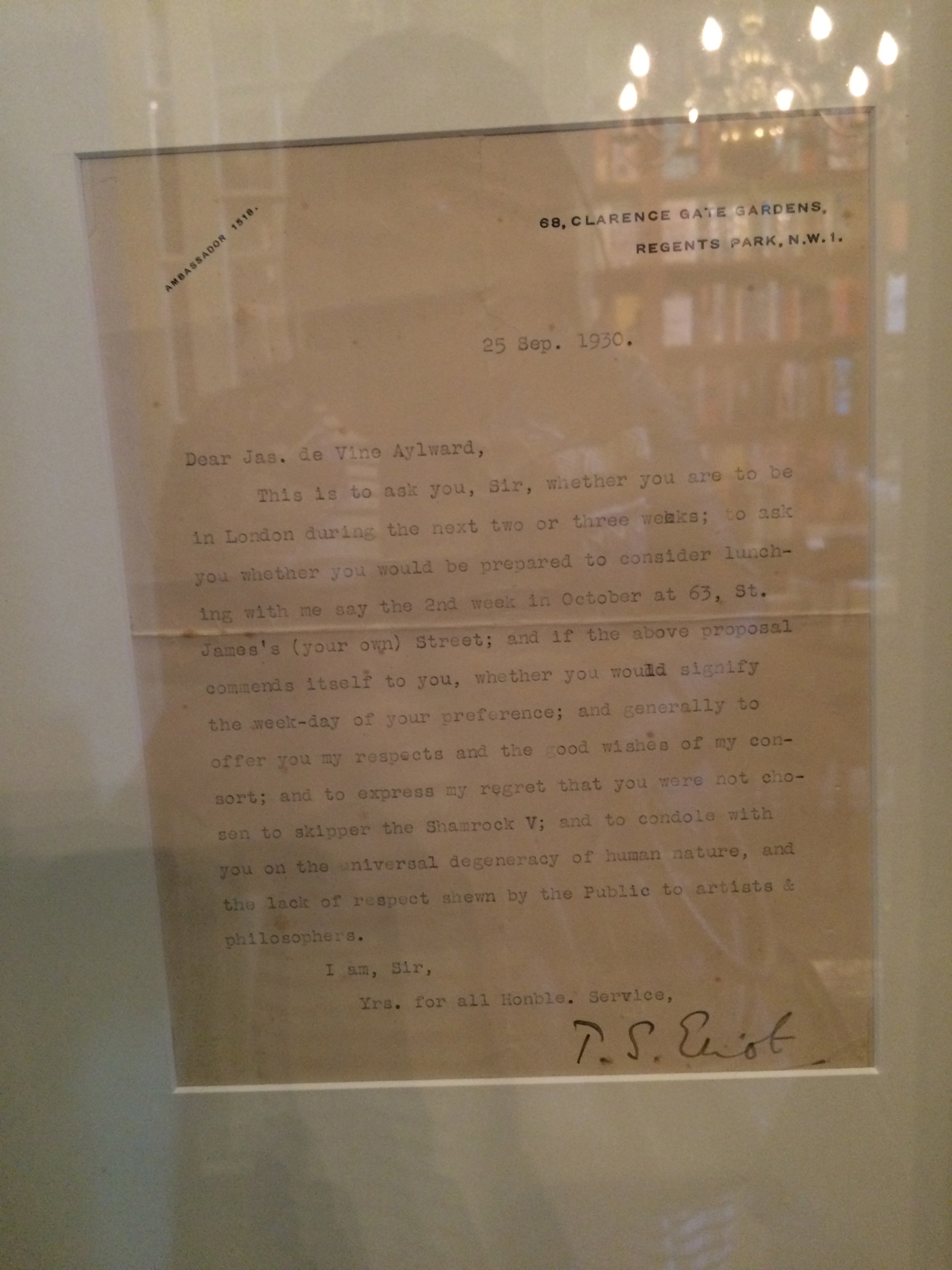

I don't know why I love this quote from William Faulkner so much "The past is not dead. In fact, it's not even past." I guess my encounter with this letter from T.S. Eliot provides an eerie reminder of this living past. It makes me recall a seminar from one of my history professors wherein she brought up the subject of defining history usually debated in graduate school. It's a common inquiry that many historians question- that is, when does history start ? Does history begin a decade, five years, a month, five seconds from the present time? Although I don't have any answers to this question, I decided to test the livable past and write a letter to T.S. Eliot in response to the letter he wrote to one of his colleagues.

Dear T.S. Eliot,

I want to meet with you this evening in the middle of Cafe Du Monte for coffee and beignets! I'd love to indulge you the details and exploits of my summer Bookpacking trip to Louisiana. I've explored the vibrant city of New Orleans, the state capitol of Baton Rouge, beautiful Grand Isle, and the modest city of Lafayette with my classmates from USC. Your poem, "The Waste Land" struck me and resonated with the protagonist Binx's existential crisis and search for identity in our assigned reading of Walker Percy's book, The Moviegoer. So far, I'm enjoying my time in New Orleans and hope to convene with you soon!

From,

Ogechi